Abstract

The cutaneous manifestations of sarcoid will be reviewed. These include lupus pernio, multiple varied skin presentations such as annular sarcoid, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, erythroderma, scar-like lesions, and several others. Erythema nodosum in sarcoidosis will be discussed; the Koebner phenomenon will be described; and the differential diagnosis of all of these lesions will be presented in detail. Numerous clinical photographs will be provided to help the treating clinician identify and work up the patient accordingly. The histopathology and pathologic differential diagnosis will also be discussed. Treatments for the varied skin lesions will be reviewed in detail as will the side effects of each treatment and management overview.

Keywords

- lupus pernio

- cutaneous sarcoid

- erythema nodosum

- granulomatous

- Koebner

1. Introduction

Sarcoid is a granulomatous disease that is known to affect multiple organ systems and primarily the lungs [1]. It can also affect the heart, kidneys, eyes, liver, joints, and lymph nodes [2, 3, 4]. The many clinical presentations of sarcoid has led to its being called the great imitator as many conditions are misdiagnosed as sarcoid and sarcoid is misdiagnosed as other diseases. The differential diagnosis must therefore conditions as varied as leishmaniasis, leprosy, infectious diseases, vasculitides, drug reactions, granulomatous reactions to environmental agents, lupus rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, common variable immune deficiency, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, paracoccidioidomycosis and others [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11].

The skin is commonly involved in sarcoid, affecting up to 30% of patients [12, 13].

Like the many systemic manifestations of sarcoid, the cutaneous manifestations are quite varied, and many of the cutaneous manifestations will be described below.

2. Epidemiology

Sarcoid can affect individuals of all ages, but primarily manifests in young adults. It displays heterogeneity and follows an unpredictable clinical trajectory [14]. The frequency of sarcoid varies significantly across different parts of the world. In South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan, the occurrence ranges from 1 to 5 cases per 100,000 individuals, whereas in Sweden and Canada, rates of 140 to 160 cases per 100,000 people [15]. The skin is commonly affected [12] affecting up to 30% of patients [13]. There are familial cases as well [16]. Sarcoid is most commonly found in non-Hispanic Black individuals in the United States, particularly among Black American women who exhibit the highest occurrence and prevalence rates [17]. We present a review of the pathology of cutaneous sarcoid and numerous clinical cutaneous presentations with figures.

3. Cutaneous manifestations

There are many cutaneous presentations of sarcoid. The most characteristic lesions are papules and nodules on the face called lupus pernio (Figure 1). The nose is prominently affected. It affects both African American and Caucasian patients. Papules can be found on the entrance to the nose (Figure 2) and on the ear (Figure 3). It can also occur around the lips and at the angle of the mouth (Figure 4). Lesions can be annular, (Figure 5) can appear hypopigmented (Figure 6), and hyperpigmented patches with papules (Figure 7) can also develop. The lesions of sarcoid can be scar-like and the scars can ulcerate (Figure 8) and can affect African American patients (Figure 9). Ulcerations are not rare in Caucasian or African American patients (Figure 10). Lesions can also be covered with telangiectasia and sarcoid can present with the Koebner phenomenon (Figure 11).

Figure 1.

Sarcoid, papules and nodules.

Figure 2.

KT pseudofolliculitis barbae-like sarcoid.

Figure 3.

Sarcoid FF.

Figure 4.

Sarcoid, IT, lupus pernio papules at oral commissure.

Figure 5.

Annular sarcoid lupus Pernio.

Figure 6.

Hypopigmented sarcoid.

Figure 7.

IT scar like.

Figure 8.

Sarcoid, FA.

Figure 9.

Sarcoid, KS.

Figure 10.

Sarcoid, leg ulcers.

Figure 11.

Sarcoid, scarlike with Koebner phenomenon.

The condition can mimic numerous other cutaneous diseases including hypertrophic scars (Figure 12) and psoriasis (Figure 13). Another condition that sarcoid can simulate is pseudofolliculitis barbae (Figure 14), stasis dermatitis (Figure 15), and patients can develop enlarged noses resembling rhinophyma (Figure 16). Sarcoid can resemble acne nuchae keloidalis (Figure 17) and there are patients who present with clusters of brown papules resembling lichen nitidus (Figure 18). African American patients can be affected more severely (Figures 19 and 20) [18].

Figure 12.

Sarcoid, CS presterna; scar, annular.

Figure 13.

Sarcoid, CS psoriasiform sarcoid.

Figure 14.

Sarcoid, JS resembling pseudofolliculitis.

Figure 15.

Sarcoid, L stasis dermatitis-like.

Figure 16.

Sarcoid, enlargement of nose resembling rhinophyma.

Figure 17.

Sarcoidosis, resembling acne nuchae keloidalis.

Figure 18.

Clusters of brown papules resembling lichen nitidus.

Figure 19.

Sarcoid, JW scars.

Figure 20.

Sarcoid, ulcerated scarlike.

Erythema nodosum has occurred as a reaction to sarcoid. While there are many conditions that lead to erythema nodosum, sarcoid is classically one of them. When erythema nodosum occurs in sarcoid patients, it has been said to portend a good outcome to the sarcoid (Figure 21) [19] with resolution of the disease thereafter.

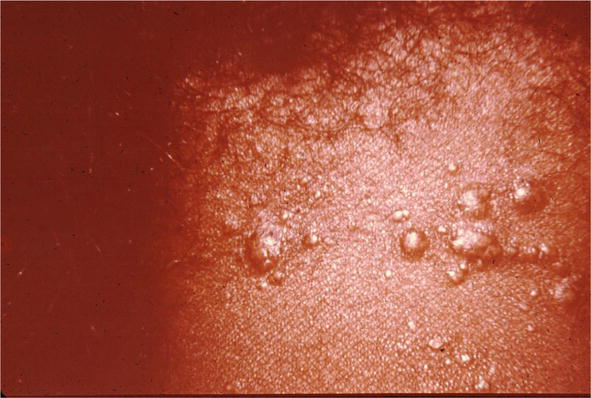

Figure 21.

Erythema Nodosum sarcoid.

Skin lesions have been treated with all the therapies that have been used for sarcoid including systemic steroids, methotrexate, antimalarials, TNF blockers [20]. The patient shown in Figure 22 was treated only with intralesional corticosteroids with complete resolution of her sarcoid (Figure 23).

Figure 22.

Annular sarcoid.

Figure 23.

Sarcoid, post Rx.

4. Histopathology

Definitive diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis will be determined by a skin biopsy to confirm the clinical impression. Although almost any type of biopsy will most likely yield an appropriate diagnosis, it imperative that the biopsy be representative. In most instances a 3 or 4 mm punch biopsy will yield enough information. However, sometimes sarcoidosis can be present in the subcutis and a deeper incisional biopsy will be necessary.

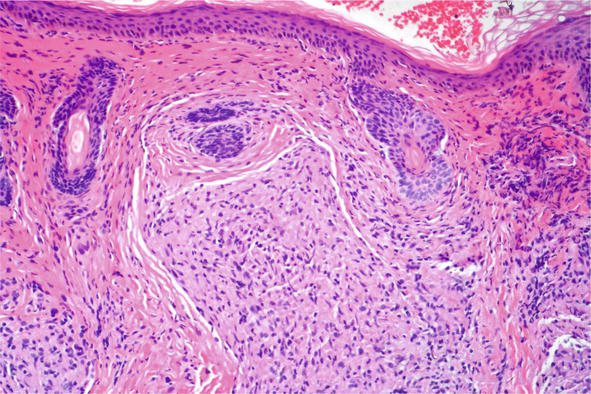

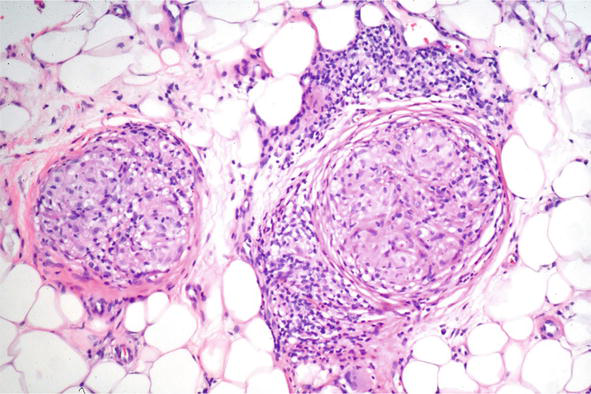

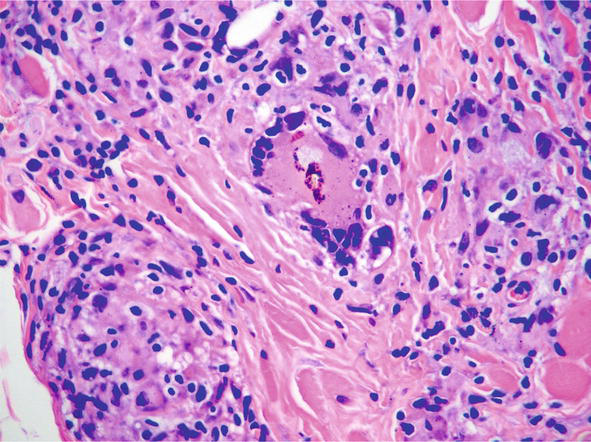

Fortunately, in most instances pathology has characteristic features. Throughout the superficial and deep dermis, there are nodular collections of epithelioid cells. The epithelioid cells have a distinctive appearance: oval histiocytes with abundant amphophilic or eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric angulated nuclei. At the periphery, frequently there are multinucleated giant cells arranged in horseshoe like shape “Langhans type giant cells” (Figure 24) Surrounding these granulomas, there is often a minimal inflammatory infiltrate so called “naked” granulomas. Within these cells there can be foci of calcification: “Schaumann bodies” or intracytoplsmic stellate inclusions “asteroid bodies”. The granulomas are often through the dermis, but in some variants can involve the subcutis and have clinical features of a panniculitis (Darier-Roussy variant) (Figure 25) [21]. In contrast to infectious granulomas, there is usually no significant necrosis and at most mild fibrinoid change. With time the lesions may show hyalinization and fibrosis.

Figure 24.

Cutaneous sarcoid, histopathology H and E,10x.

Figure 25.

Subcutaneous sarcoid, histopathology H and E, 10x.

As many other conditions can show granulomatous histology, it is important that the pathologist is able to formulate a good clinicopathologic correlation. As sarcoid clinically can mimic other conditions, exacting criteria must be used to define the condition, as well as knowing the limitations of pathology. This is particularly true in dermatology and dermatopathology as many simulators exist.

The following disorders can mimic sarcoid: rosacea-like dermatoses, tuberculous leprosy, reactions to environmental injury (tattoos, metal and industrial exposures, foreign body reactions) lupus vulgaris, infectious granulomas, tuberculids, necrobiotic granulomas and granulomatous vasculitides.

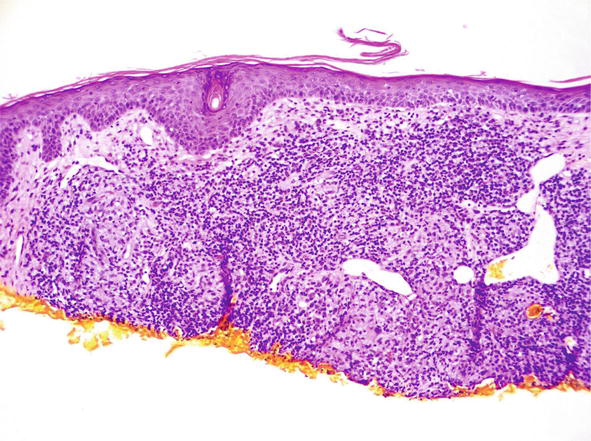

Granulomatous rosacea is an acneiform dermatosis, that can mimic sarcoid clinically and pathologically [22]. Certain clinical variants of the conditions, such perioral dermatitis, lupus miliaris disseminates faciei also occur commonly on facial skin – areas where sarcoid presents. If a granlulomatous condition is evident on facial skin, the pathologist must exercise care in defining it as sarcoid or not. In most types of granulomatous rosacea, there are histologic features which deviate from the typical presentation of sarcoid. First, the granulomatous are most often inflammatory, i.e., surrounded by mononuclear cells, particularly plasma cells. Second, in adjacent skin, there often are features of other types of rosacea – with other pustules or telangiectasia of the erythematotelangiectatic type (Figure 26). Despite these clues, there are rosacea like dermatoses, particularly childhood types – disseminated periorificial dermatitis, where these clues may not be present. In those cases, the pathologist should state their uncertainty in the report and advise that the diagnosis may have to be confirmed by other means – laboratory studies or clinical trials.

Figure 26.

Granulomatous rosacea, histopathology H and E, 10x.

Tuberculoid leprosy may mimic sarcoid clinically with annular lesions but often there are other features that allow for a clinical distinction, such enlarged peripheral nerves, loss of sensation, anhidrosis or travel history. Pathologically, it can much more difficult. There can be nodular collections of epithelioid cells with a sparse infiltrate. Things to look for which favor tuberculoid leprosy: oval granulomas, following peripheral nerves and destruction of those nerves by the granulomas. Fite or auramine O stain can helpful for demonstrating organisms but more often than not the number of bacilli are few or undetectable.

Reactions to foreign substances can also mimic sarcoid. Reactions to tattoos may show sarcoidal, granulomas (Figure 27), corals, sea urchins, and cacti can show granulomatous histology. Sometimes the reaction can be of a foreign body type, and later become more sarcoidal [23]. Similar reactions may occur to heavy metals (zicornium, beryllium). Even though these agents can cause this type of reaction, it still may be necessary to exclude sarcoidosis. Sarcoid can often localize to areas of antecedent injury –so called locus minoris resistentiae. Often it is necessary to state that localization of sarcoid cannot be excluded.

Figure 27.

Granulomatous reaction to tattoo, histopathology H and E, 20x.

Infectious granulomas are also in the differential. This is perhaps the most important category to exclude unequivocally, as the therapy is the opposite of sarcoid – antimicrobial versus immunosuppressive. Principal among these are mycobacterial infections both atypical types and tuberculous. In general infectious mycobacterial reactions have some clue to their genesis – necrosis within the granulomas, an adjacent suppurative or mononuclear infiltrate, or epidermal hyperplasia. Unfortunately, particularly in rare subtypes of atypical mycobacteria, the distinction may be very difficult if not impossible. In those cases, sometimes the clinical parameters are paramount – do the lesions show sporotrichoid spread? Is there a recent onset? Is there a history of an occupational, or local exposure? In those equivocal cases, special stains, culture or PCR should be performed.

Other infections conditions can also show granulomas – deep fungal infections, and leishmania. Fortunately, organisms are usually easily visualized in the acute and subacute stages, though with chronicity can be less evident. In addition to special stains, additional microbiologic studies may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Tuberculids refer to lesions that arise in patients as a hypersensitivity reaction to the tubercle bacilli, distant from the site of the primary infection. There are many clinical types – papulonecrotic tuberculids, lichen scrofulosorum, and erythema induratum [24]. These entities all show well defined granulomas often with necrosis but with limited evidence of an active infection. Treatment of the primary infection usually results in resolution of the process.

Other miscellaneous conditions can show granulomas. Metastatic Crohn’s disease can show small granulomas distant from primary lesions of the disease [25]. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and granulomatous cheilitis can also show small collections of epithelioid cells, often with adjacent lymphangiectasia [26]. Deep folliculitides, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, though often showing foreign body granulomas, can sometimes have a sarcoidal pathology as well. Certain necobiotic granuomas such as granuloma annulare can show sarcoid; lymphoproliferative disorders can show a focal granulatous histology [27]. In all of these conditions, the clinical appearance is paramount in making the correct diagnosis.

From this perspective the pathologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis is vast. Many other conditions can mimic and often the diagnosis is one of exclusion. In all cases it is essential the pathologist have access to clinical information and often clinical photographs; and that all special stains be performed as necessary: including infectious disease stains, acid fast, fite and other bacterial stains; other stains be performed if the differential includes a necrobiotic granuloma, such as shiktata, Voerhoeff von gieson and colloidal iron. If the granulomas are void of an inflammatory infiltrate, if there is no significant ulceration or substantial epidermal hyperplasia, the diagnosis can be suggested.

5. Summary

Sarcoid can be very variable in its clinical presentations and course. The systemic manifestations of sarcoid can mimic those of many conditions. Likewise, the cutaneous manifestations of sarcoid can be very variable and can mimic many cutaneous disorders. Clinicians must maintain a healthy level of suspicion when a diagnosis of sarcoid is considered.

References

- 1.

Spagnolo P, Rossi G, Trisolini R, Sverzellati N, Baughman RP, Wells AU. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2018; 6 (5):389-402. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30064-X - 2.

Markatis E, Afthinos A, Antonakis E, Papanikolaou IC. Cardiac sarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2020; 21 (3):321-338. DOI: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.03.102 - 3.

Calatroni M, Moroni G, Reggiani F, Ponticelli C. Renal sarcoidosis. Journal of Nephrology. 2023; 36 (1):5-15. DOI: 10.1007/s40620-022-01369-y - 4.

Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, Salazar A, Peyrí J, Pujol R. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. Relationship to systemic disease. Archives of Dermatology. 1997; 133 (7):882-888. DOI: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013 - 5.

Kundakci N, Erdem C. Leprosy: A great imitator. Clinics in Dermatology. 2019; 37 (3):200-212. DOI: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.01.002 - 6.

Gurel MS, Tekin B, Uzun S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: A great imitator. Clinics in Dermatology. 2020; 38 (2):140-151. DOI: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.008 - 7.

Judson MA. Granulomatous Sarcoidosis Mimics. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021; 8 :680989. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2021.680989 - 8.

Torralba KD, Quismorio FP Jr. Sarcoidosis and the rheumatologist. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2009; 21 (1):62-70. DOI: 10.1097/bor.0b013e32831dde88 - 9.

Shanks AM, Alluri R, Herriot R, Dempsey O. Misdiagnosis of common variable immune deficiency. BML Case Reports. 2014; 2014 :bcr2013202806. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202806 - 10.

Sarmento Tatagiba L, Bridi Pivatto L, Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Mendes Peçanha P, Grão Velloso TR, Santos Gonçalves S, et al. A case of paracoccidioidomycosis due to Paracoccidioides lutzii presenting sarcoid-like form. Medical Mycology Case Reports. 2017;19 :6-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2017.09.002 - 11.

Alexandra G, Claudia G. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis mimicking cancer and sarcoidosis. Annals of Hematology. 2019; 98 (5):1309-1311. DOI: 10.1007/s00277-018-3505-4 - 12.

Ezeh N, Caplan A, Rosenbach M, Imadojemu S. Cutaneous Sarcoidosis. Dermatologic Clinics. 2023; 41 (3):455-470. DOI: 10.1016/j.det.2023.02.012 - 13.

Amschler K, Seitz CS. Kutane Manifestationen bei Sarkoidose [cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis]. Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie. 2017; 76 (5):382-390. German. DOI: 10.1007/s00393-017-0290-8 - 14.

Bargagli E, Prasse A. Sarcoidosis: A review for the internist. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2018; 13 (3):325-331. DOI: 10.1007/s11739-017-1778-6 - 15.

Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: Recent estimates of incidence, prevalence and risk factors. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2020; 26 (5):527-534. DOI: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000715 - 16.

Spagnolo P, Maier LA. Genetics in sarcoidosis. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2021; 27 (5):423-429. DOI: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000798 - 17.

Wills AB, Adjemian J, Fontana JR, et al. Sarcoidosis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2018; 15 (12):1490-1493 - 18.

Hena KM. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: Race matters. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020; 11 :537382. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.537382 - 19.

Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: An analysis of 818 patients. The Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 1983; 52 (208):525-533 - 20.

Dai C, Shih S, Ansari A, Kwak Y, Sami N. Biologic therapy in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis: A literature review. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2019; 20 (3):409-422. DOI: 10.1007/s40257-019-00428-8 - 21.

Marcoval J et al. Histopathological features of subcutaneous sarcoidosis. The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 2020; 42 (4):233-243 - 22.

Lee GL et al. Granulomatous rosacea and periorificial dermatitis: Controversies and review of management and treatment. Dermatologic Clinics. 2015; 33 (3):447-455 - 23.

Lim D et al. Sarcoidal reaction in a tattoo. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382 (8):744 - 24.

Feuer J, Phelps RG, Kerr LD. Erythema nodosum vs erythema induratum: A crucial distinction enabling recognition of occult tuberculosis. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 1995; 1 :357-362 - 25.

Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: A histopathologic study of 12 cases. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. May 2008; 35 (5):457-461 - 26.

Lenskaya V, de Moll EH, Bhatt S, Hussein S, Phelps RG. The subtlety of granulomatous mycosis Fungoides: A retrospective case-series study and proposal of novel multimodal diagnostic approach and literature review. American Journal of Dermatopathology. 2022; 44 (8):559-567 - 27.

Lenskaya V, Panji P, de Moll EH, Christian K, Phelps RG. Oral lymphangiectasia and gastrointestinal Crohn disease. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2020; 47 (11):1080-1084