Ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis (adapted from Ref. [1]).

Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a complex granulomatous systemic inflammatory disease that can affect the eye and its adnexa. Ocular sarcoidosis is a leading cause of inflammatory eye disease that can result in significant visual impairment. Ocular inflammation can manifest with a wide range of clinical presentations and can involve almost any structure within or around the orbit causing uveitis, episcleritis/scleritis, eyelid anomalies, conjunctival granulomas, optic neuropathy, lacrimal gland enlargement, glaucoma, and/or cataract. The diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis is typically established based on the presence of characteristic ophthalmologic findings, along with a positive tissue biopsy or bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest imaging. Topical, periocular, and systemic corticosteroids are commonly used to treat ocular sarcoidosis. Chronic cases or refractory cases may warrant immunomodulator therapy. Visual prognosis is contingent on severity of inflammation, time to treatment, and secondary ocular complications. This chapter will discuss the presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of patients with ocular sarcoidosis.

Keywords

- granulomatous uveitis

- ocular granulomatosis

- ocular sarcoidosis

- sarcoid uveitis

- sarcoidosis-related uveitis

1. Introduction

Ocular disease may be the first manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis [1]. The reported incidence of ocular involvement in sarcoidosis ranges from 13 to 79%, with approximately 20–30% presenting with ocular symptoms as the primary manifestation [1, 2, 3, 4]. Ocular sarcoidosis can affect many ocular tissues simultaneously with several clinical presentations; thus, diagnosis can be challenging. Typical ocular symptoms include redness, decreased vision, photophobia, and/or eye pain.

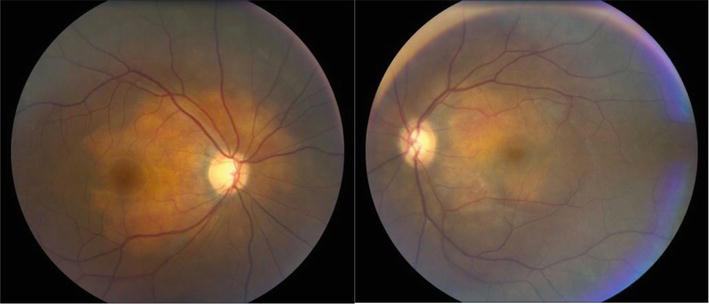

The most common presentation of ocular sarcoidosis is uveitis [5]. Uveitis is a term used by ophthalmologists to describe inflammation of the uveal tissues, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Uveitis can be classified by the anatomic location of the observed inflammation seen by the ophthalmologist using the slit lamp to examine the eye. The most universally accepted formal uveitis classification and grading scheme used by ophthalmologists was published by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group [1, 5]. The SUN Working Group is an international uveitis collaboration and has developed a classification criteria for the leading causes of ocular inflammation, which includes sarcoidosis-associated uveitis. When classifying by anatomic location, uveitis can present as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis. The typical presentation of sarcoid uveitis is characterized by granulomatous inflammation with large mutton-fat keratic precipitates (KP), nodules on the pupillary margin (Koeppe nodules) or within the iris stroma (Busacca nodules), or choroidal granulomas (Figure 1) [6]. This chapter will describe these ocular findings, diagnosis, and treatment strategies. An overview of ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis is displayed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Bilateral choroidal granulomas in a 33-year-old female with sarcoidosis (photo courtesy of Calgary retina consultants).

| Ocular structures | Findings |

|---|---|

| Eyelids | Eyelid granuloma, madarosis (loss of eyelashes), poliosis (whitening of lashes), entropion, trichiasis, lagoghthalmos (if associated with facial palsy) |

| Extraocular muscles and orbital tissues | Strabismus, proptosis, optic nerve compression |

| Conjunctiva | Conjunctival nodules, conjunctivitis, symblepharon |

| Sclera and Episclera | Episcleritis, scleritis |

| Cornea | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca |

| Iris | Iris nodules, posterior synechiae |

| Anterior chamber | Inflammatory cell, KP |

| Trabecular meshwork | Angle granulomas, peripheral anterior synechiae |

| Lens | Cataract, posterior synechiae |

| Vitreous | Vitreous cell, snowballs, snowbanks |

| Retina and choroid | Retinitis, vasculitis, CME, Choroiditis, Choroidal granulomas |

| Optic nerve and visual pathways | Relative afferent pupillary defects, visual field defects, abnormal eye movement, optic nerve inflammation or granulomas |

Table 1.

2. Demographics

Uveitis has been reported in 30–70% of ocular sarcoidosis cases and is one of the most common manifestations of the disease [1]. Among patients with systemic sarcoidosis, females are more likely to develop ocular involvement compared to males [1]. The age distribution of ocular sarcoidosis in adults demonstrates a bimodal presentation with peaks of incidence between the ages of 20

Individuals of pigmented race with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis have a higher likelihood of developing ocular involvement compared to Caucasians. There is also evidence for the allelic variations at the HLA-DRB1 locus as a contributing factor for sarcoidosis; specifically, the HLA-DRB1*0401 allele has been associated with ocular involvement [1]. Patients with ocular sarcoidosis appear to have less systemic involvement albeit with varying reported rates. For instance, out of 294 patients with sarcoid uveitis, only 2.4% of them developed cardiac involvement [7], while another study reported 4.4% of cardiac sarcoidosis in a retrospective cohort of sarcoid uveitis [8].

3. Ocular manifestations of sarcoidosis

3.1 Anterior segment findings

The anterior segment of the eye includes the cornea, anterior chamber, iris, and lens. Anterior chamber inflammation is the most common ocular presentation of sarcoidosis. In one study, anterior chamber involvement was detected in 42 out of 46 patients (91%) with biopsy-confirmed sarcoid uveitis. Thirty-eight of these patients had solely anterior chamber involvement [9]. Characteristic clinical presentations associated with anterior chamber inflammation include redness, eye pain, decreased vision, and photophobia. Pain associated with uveitis can occur secondary to ciliary muscle spasm or elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Elevated IOP may be secondary to blockage of the aqueous outflow pathway, known as the trabecular meshwork, by inflammatory cells, sarcoid nodules, or adhesion of the peripheral iris to the peripheral cornea (peripheral anterior synechiae) [1, 6]. Keratic precipitates are visualized when anterior chamber leukocytes precipitate onto the posterior surface of the cornea [1, 6]. The size of these KPs varies, and larger KPs are typically seen in cases of granulomatous uveitis. Granulomatous uveitis is a specific pattern of uveitis that is seen with a small number of uveitis causes and includes sarcoidosis. Granulomatous uveitis must have at least one of the following clinical signs: large mutton-fat KP, iris or trabecular meshwork nodules, and/or choroidal granulomas. However, these clinical findings may not be observed in all cases of ocular sarcoidosis, especially in early or mild disease [1].

Iris involvement is also common. Untreated anterior uveitis can lead to iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule (posterior synechiae) can cause an irregularly shaped pupil [1]. Severe posterior synechiae can lead to a completely occluded pupil known as iris bombe, and this is often associated with increased IOP. Cataract formation can develop secondary to persistent inflammation as well as treatment with topical corticosteroids [1, 6].

3.2 Posterior segment findings

The posterior segment of the eye includes the following eye structures: vitreous humor, the retina, the choroid, and the optic nerve. Posterior uveitis is less common than anterior uveitis but is often more vision threatening [6].

Intermediate uveitis mainly affects the vitreous and peripheral retina and is a common presentation of ocular sarcoidosis. Symptoms of intermediate uveitis include floaters and decreased vision. In contrast to patients with anterior segment inflammation, patients with intermediate uveitis tend to experience less pain. On examination with the slit lamp biomicroscope, vitreous cells may be observed. Cystoid macular edema (CME) can be seen on fundus examination or with the aid of imaging tools such as optical coherence tomography. Inflammatory cells can accumulate inferiorly in the vitreous cavity along the pars plana. When the inflammatory debris in this area collect in sheets, they are called “snowbanks”; meanwhile, when found in focal consolidations, they are known as “snowballs” or “string of pearls” [1, 6].

Inflammation of the retina and choroid, respectively known as retinitis and choroiditis, may also be seen in ocular sarcoidosis. Vascular inflammation can present as perivascular sheathing. Deposition of white-yellow perivascular exudates in the retina alongside the retinal veins and is called “candle-wax drippings” [1, 6]. Generally, ocular sarcoidosis does not cause retinal vascular occlusion but has been reported in approximately 5% of cases [5, 6]. If occlusion occurs acutely or with chronic or untreated retinal vasculitis or intermediate uveitis, retinal neovascularization may develop. This can cause vitreous hemorrhage if severe. Fluorescein angiography is an imaging modality that can assess the retinal vasculature and severity of retinal inflammation. Posterior uveitis is generally associated with more frequent relapses and a poorer visual prognosis [6].

Similar to sarcoid granulomas observed in the other parts of the body, granulomas can develop in the retina and choroid. These granulomas may be unifocal or multifocal and can vary in size. Visual changes can vary depending on the location of these granulomas and can range to asymptomatic if located in the peripheral retina to severe vision decline if located in the macula, the retinal area responsible for central vision. Exudative retinal detachments can be associated with larger granulomas, although this finding is rare [1, 5, 6].

Optic nerve findings in sarcoidosis may include optic nerve granulomas, optic disc edema, or disc hyperemia. If inflammation is severe or chronic, optic atrophy with irreversibly impaired vision may result. Pupillary abnormalities, such as a relative pupillary defect can be noted on exam with optic nerve involvement or damage [1].

Finally, panuveitis describes inflammation affecting all structures of the uvea and accounts for approximately 37% of sarcoid uveitis by the SUN working group [5]. Sarcoidosis is the most frequently systemic disease associated with panuveitis [6].

3.3 Orbital involvement

The orbit includes the lacrimal gland, orbital fat, extraocular muscles, and the optic nerve sheath [1]. Infiltration or inflammation of the lacrimal gland and muscles from ocular sarcoidosis may present with a palpable eyelid mass and eyelid swelling [1]. Other symptoms indicating orbital involvement include globe displacement, ptosis, proptosis, pain, redness and tearing. Double vision (diplopia) can occur if cranial nerves are compressed or by mass effect. Vision loss can result in severe cases if the optic nerve is compressed.

Coexisting systemic sarcoidosis are present in approximately 34–50% of biopsy-proven orbital sarcoidosis [1]. Orbital sarcoidosis lesions tend to be well circumscribed on imaging in 85–90% of patients, with 10–15% of diffuse or infiltrative patterns noted [1]. On histopathology and gross examination, orbital lesions tend to be solid as opposed to cystic [10].

The lacrimal gland is the most common orbital structure affected by sarcoidosis [1]. Patients with lacrimal gland involvement may or may not be symptomatic. The lacrimal gland produces the aqueous component of the tear film; therefore, patients may complain of dry eye symptoms when the gland is infiltrated by sarcoid granulomas or is inflamed. If the lacrimal gland is significantly enlarged, symptoms secondary to mass effect can result as mentioned above.

3.4 Eyelid and ocular surface

Eyelid granulomas may vary in size from small papules to larger lesions that can distort eyelid architecture [1]. Madarosis or loss of eyelashes may occur but is typically seen with more invasive and destructive eyelid tumors. Infiltration or inflammation of the lacrimal drainage system, which consists of the canaliculi, nasolacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct, may manifest as excessive tearing [1].

Corneal involvement can manifest as superficial punctate keratitis secondary to dry eye syndrome, known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca. This occurs secondary to lacrimal gland inflammation/infiltration. Episcleritis and scleritis are uncommonly associated with sarcoidosis [1]. Scleritis may present as anterior diffuse, anterior nodular, or posterior scleritis. Common symptoms of scleritis include ocular pain and redness. Vision is often unaffected [1].

Conjunctival involvement is common, and nodules have been reported in 40% of cases [2]. However, granulomas in this area tend to be small and asymptomatic. Conjunctivitis can be mild with ocular redness and follicular conjunctivitis or can be severe with scarring, symblepharon and fornix shortening. Larger granulomas can mimic conjunctival tumors [1]. Conjunctival granulomas may present as white-yellow, discrete infiltrates and can vary in size. Sarcoid conjunctival nodules are commonly observed at the palpebral conjunctivae; however, they may also be located at other locations [1].

3.5 Glaucoma

Elevated IOP can be seen secondary to anterior chamber sarcoid uveitis. As discussed above, anterior chamber inflammation can cause iris adhesions to the trabecular meshwork (peripheral anterior synechiae) resulting in angle closure glaucoma and elevated IOP [1]. These patients can be managed with ocular hypotensive eye drops but may ultimately require glaucoma surgery. Elevated IOP can also be caused by orbital mass effect and prolonged steroid therapy. The latter is thought to be secondary to changes in the microstructure of trabecular meshwork, resulting in swelling and an increase in outflow resistance of aqueous fluid [11].

3.6 Neurosarcoidosis

Visual symptoms of neurosarcoidosis are associated with the location of granuloma formation and inflammation. Symptoms include decreased vision and visual field defects, papilledema secondary to increased intracranial pressure, abnormal eye movement, pupillary abnormalities, and peripheral neuropathy [1]. Cranial neuropathy involving the optic and facial nerves can occur secondary to neurosarcoidosis. As a result, facial paresis is a common presentation due to parotid gland inflammation. Additionally, lower motor neuron facial paresis can cause ipsilateral poor eyelid closure, which can result in exposure keratopathy and possible corneal ulcers [1].

4. Diagnosis

Sarcoidosis is a difficult diagnosis for clinicians given that it can involve many organs, ocular tissues, and may manifest in different clinical presentations. This condition most commonly affects the lungs and hilar lymph nodes [1, 5]. However, many patients are asymptomatic and may be diagnosed upon routine exam, further complicating initiation of timely treatment. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis includes three important criteria: (1) consistent clinical presentation, (2) presence of non-caseating granulomas in one or more tissue samples, and (3) exclusion of other causes of granulomatous disorders [6]. The World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) created consensus criteria to categorize the likelihood of a sarcoid diagnosis that has been revised and updated over time. For example, sarcoidosis was highly probable given symptoms of uveitis or findings of bilateral hilar lymph nodes, or perilymphatic nodules on chest computed tomography scan (CT). It was considered probable with cranial nerve infiltration, lacrimal gland swelling, and/or upper lobe or diffuse infiltrates on chest CT. Arthralgia and/or localized infiltrates on chest CT suggested a possible but less likely diagnosis [6]. It is also important to rule out differential diagnoses of ocular sarcoidosis which include infections such as tuberculosis and malignancies such as lymphoma [6]. The Classification Criteria for Sarcoid Uveitis published by the SUN Working Group is shown in Table 2.

| Criteria |

1. Compatible uveitic picture, either

2. Evidence of sarcoidosis, either

|

| Exclusions |

| 1. Positive serology for syphilis using a treponemal test 2. Evidence of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis,* either |

Table 2.

Classification criteria for sarcoid uveitis (adapted from the SUN working Group5).

Routine exclusion of tuberculosis is not required in areas where tuberculosis is non-endemic but should be performed in areas where tuberculosis is endemic or in tuberculosis-exposed patients. With evidence of latent tuberculosis in a patient with a uveitic syndrome compatible with either sarcoidosis or tubercular uveitis and bilateral hilar adenopathy, the classification as sarcoid uveitis can be made only with biopsy confirmation of sarcoidosis (and therefore exclusion of tuberculosis).

E.g. Biopsy, fluorochrome stain, culture, or polymerase chain reaction based assay.

E.g. Quantiferon-gold or T-spot.

E.g. Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test; a positive result should be >10 mm induration.

Generally, sarcoidosis should be high on the differential in cases where there are multiple ocular tissues involved. Ophthalmologists will initiate a focused uveitis workup depending on the pattern of inflammation and ocular findings observed. The gold standard for diagnosis of sarcoidosis includes tissue biopsy from an affected area from the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, conjunctiva, lacrimal glands, or orbital tissues [1]. However, given that a biopsy is not feasible in many cases, guidelines from the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis have been published which recommend laboratory tests when a biopsy is not performed or results negative [12]. Imaging, such as a chest x-ray or chest CT can help confirm diagnosis when sarcoidosis is suspected. Patients may also have elevated biomarkers including calcium, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), and/or lysozyme [1].

5. Treatment

Generally, sarcoid uveitis is treated with corticosteroids. The selection of the steroid administration route (e.g. periocular, intraocular, systemic) and the addition of corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulators is primarily determined by the extent of inflammation, ocular or adnexal tissues involved, and whether the inflammation is unilateral or bilateral. Furthermore, the use of topical cycloplegic eye drops can help relieve pain from ciliary spasm and to reduce posterior synechiae [1]. For scleritis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually prescribed as first-line therapy. In uveitis with posterior segment involvement, regional corticosteroid injections such as triamcinolone acetonide (1–4 mg) and steroid implants can be considered. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, namely, infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and golimumab, are considered as novel treatment options, although scientific evidence remains limited to small studies [1].

Common ocular complications of ocular sarcoidosis include cataract, epiretinal membrane formation and glaucoma, and patients need to be regularly assessed for the development of these conditions [1]. Corticosteroid therapy should be managed carefully in patients with elevated IOP. Systemic immunosuppressant medications also need to be monitored for systemic side effects.

6. Prognosis

The visual prognosis of ocular sarcoidosis is highly dependent on the severity of inflammation, chronicity of underlying disease, time to presentation to an ophthalmologist, and presence of ocular complications [1]. One paper which followed sarcoid uveitis patients over a median of 4 years determined that 54% of patients retained normal vision acuity (20/40 or better), and only 4.6% of patients lost vision to worse than 20/120 bilaterally [13]. Generally, regular follow-up and medication compliance are essential for a favorable prognosis.

7. Conclusion

A multidisciplinary approach is essential to optimize treatment outcomes for both ocular and systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Effective communication and collaboration between ophthalmologists and non-ophthalmologists are key to providing comprehensive care. With early diagnosis and appropriate management, visual prognosis for patients with ocular sarcoidosis is generally good. Larger longitudinal prospective studies are recommended to continue to advance the guidelines on management of patients with sarcoid uveitis.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Calgary Retina Consultants for providing clinical photos.

References

- 1.

Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 2015; 36 :669-683. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.009 - 2.

Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000; 84 :110-116. DOI: 10.1136/bjo.84.1.110 - 3.

Atmaca LS, Atmaca-Sönmez P, Idil A, Kumbasar ÖÖ, Çelik G. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2009; 17 :91-94. DOI: 10.1080/09273940802596526 - 4.

Heiligenhaus A, Wefelmeyer D, Wefelmeyer E, Rösel M, Schrenk M. The eye as a common site for the early clinical manifestation of sarcoidosis. Ophthalmic Research. 2011; 46 :9-12. DOI: 10.1159/000321947 - 5.

Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification criteria for sarcoidosis-associated uveitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021; 228 :220-230. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.047 - 6.

Giorguitti S, Jacquot R, El Jammal T, Bert A, Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, et al. Sarcoidosis-related uveitis: A review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12 (9):3194. DOI: 10.3390/jcm12093194 - 7.

Richard M, Jamilloux Y, Courand P-Y, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis is uncommon in patients with isolated sarcoid uveitis: Outcome of 294 cases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10 (10):2146. DOI: 10.3390/jcm10102146 - 8.

Niederer RL, Ma SP, Wilsher ML, et al. Systemic associations of sarcoid uveitis: Correlation with uveitis phenotype and ethnicity. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021; 229 :169-175. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.003 - 9.

Crick RP, Hoyle C, Smellie H. The eyes in sarcoidosis. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1961; 45 (7):461-481. DOI: 10.1136/bjo.45.7.461 - 10.

Demirci H, Christianson MD. Orbital and adnexal involvement in sarcoidosis: Analysis of clinical features and systemic disease In 30 cases. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010; 151 (6):1074-1080. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.12.011 - 11.

Phulke S, Kaushik S, Kaur S, et al. Steroid-induced glaucoma: An avoidable irreversible blindness. Journal of Current Glaucoma Practice. 2017; 11 (2):67-72. DOI: 10.5005/jp-journals-l0028-1226 - 12.

Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: Results of the first international workshop on ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2009; 17 (3):160-169. DOI: 10.1080/09273940902818861 - 13.

Edelsten C, Pearson A, Joynes E, Stanford MR, Graham EM. The ocular and systemic prognosis of patients presenting with sarcoid uveitis. Eye. 1999; 13 :748-753. DOI: 10.1038/eye.1999.221