Abstract

The clinical manifestation of breast sarcoidosis accounts for <1% of cases of sarcoidosis and typically presents in the setting of already documented systemic involvement. Within the breast, sarcoidosis can often present as a firm palpable mass in young or middle-aged women. On mammography, imaging findings range from small, well-defined round masses to irregular, spiculated masses. Ultrasound most commonly demonstrates an ill-defined hypoechoic mass. As a result, breast sarcoidosis can mimic benign and malignant pathologies such as fat necrosis, fibroadenoma or breast cancer. This variability in imaging appearance represents a diagnostic challenge often culminating in image-guided or surgical biopsy and histological analysis to establish a definitive diagnosis. Ultimately, while breast involvement is uncommon, it accentuates the diverse clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis, which may be clinically suspected and must be adequately evaluated to exclude more significant pathologies.

Keywords

- breast

- sarcoidosis

- granulomas

- mammography

- ultrasound

- MRI

- granulomatous

- inflammation

- mastitis

- autoimmune

1. Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystemic disease characterized by the formation of granulomas in various organs as a consequence of an antigen-driven inflammatory response of unknown etiology [1]. These noncaseating granulomatous lesions most commonly affect the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes, but can also be found in the skin, eyes, liver, and less frequently, the breasts. Breast sarcoidosis accounts for less than 1% of sarcoidosis cases and typically presents in the setting of widespread disease [2]. The complexity of the clinical presentation is a major factor in prolonging the time to diagnosis and contributing to the lack of or inappropriate treatment [3]. The criteria for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis are largely subjective and have yet to be standardized. This makes way for the misdiagnosis of sarcoidosis with other granulomatous diseases because of the similarity and overlap of clinical, radiographic, and histological features, which poses a diagnostic dilemma [4].

Mammography and ultrasonography are the first-line imaging modalities most utilized in breast imaging, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used more secondarily as a problem-solving tool or after a diagnosis has been made for treatment planning. Imaging in breast sarcoidosis is usually followed by histological analysis of the symptomatic or incidentally encountered breast mass, regardless of the level of suspicion of sarcoidosis, unless the main differential diagnoses include benign and probably benign findings for which short–interval follow up is opted to document long term stability. The presence of non-necrotizing granulomas suggests a diagnosis of breast sarcoidosis, particularly if supporting clinical factors and past medical history are present. Once the diagnosis is established, corticosteroid therapy may be considered as a first-line treatment [1].

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the clinical, radiological, and histopathological presentation of breast sarcoidosis, focusing on conventional imaging methods while addressing the challenges associated with an accurate and timely diagnosis.

2. Epidemiology and demographics

Identifying risk factors, and patterns in the distribution and occurrence of sarcoidosis can aid our understanding of the disease and help build a framework geared towards disease prevention. Epidemiologic studies have shown the highest incidence and prevalence rates to be in African American patients and in patients in the Nordic region. The lowest incidence and prevalence rates were seen in Hispanic and Asian patients [5]. Sarcoidosis generally affects 20 to 40-year-old individuals with a higher prevalence in women (1.3%) than in men (1%). African American women have the highest disease prevalence [6]. However, the true incidence and prevalence of sarcoidosis remains undetermined because of the fact that many patients are asymptomatic [7].

Variations in the age and presentation between men and women have been reported in the literature but the data remains inconsistent. One of the most consistent findings across multiple studies is the reduced risk of sarcoidosis in individuals who smoke compared to individuals who do not smoke [5].

Potential risk factors of sarcoidosis include obesity, having a first degree relative with sarcoidosis, and having a history of infection. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis in more than one family member suggests that genetics holds a potential role in the disease process [1, 8]. Conversely, several studies have reported sarcoidosis as a risk factor for malignancy [5].

3. Clinical presentation

Breast sarcoidosis is most often seen in the setting of systemic disease, but it can also be the primary manifestation of sarcoidosis [7]. The workup can ensue after abnormal findings are detected on either a screening mammography, a screening breast ultrasound, or as a result of an incidental finding on chest imaging. These patients typically present without any complaints or breast masses [2, 3, 9]. Symptomatic patients, on the other hand, usually present because of a self-detected breast mass [10]. In general, clinical manifestations of breast sarcoidosis can be unilateral or bilateral and may include: palpable mass, breast tenderness, lymphadenopathy, nipple changes, and skin abnormalities [6, 7, 11].

In most breast sarcoidosis cases, the physical exam on initial presentation reveals a single firm, mobile, and non-tender mass. Prior pooled studies have described mass diameter ranges from 0.25 to 5 cm in size. Enlarged ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes is also fairly common and is well within the purview of a typical breast focused clinical and imaging examination. Fixed or painful lesions are less common clinical manifestations. When present, skin findings can include skin retraction, dimpling, or

Although more commonly observed in females, breast sarcoidosis can also affect male patients. In searching the literature, only one case report involving male breast tissue was found. An African American man with an established diagnosis of lung sarcoidosis presented with bilateral breast tenderness and palpable nodules determined to be sarcoidosis involving the breast tissue after biopsy [6].

Given the heterogeneity of this clinical presentation, the differential diagnosis often includes benign and malignant disease processes such as a fibroadenoma, mastitis, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, and certainly breast cancer. While malignancy is the most important diagnosis to rule out in a patient presenting with a symptomatic breast finding, it is important to consider common benign etiologies to manage them accordingly. For a palpable tender breast mass of acute onset, a mastitis may be considered, and management may begin with the least invasive intervention, such as starting with antibiotics and a follow-up ultrasound [1]. An elevated serum level of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is a strong indicator of sarcoidosis but has poor specificity and renders it an unreliable biomarker for diagnostic purposes. As a result, histologic evidence of sarcoidosis in breast tissue is most often necessary for diagnosis [11, 12].

4. Pathology

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic disease of unknown etiology characterized by non-necrotizing granulomas. The lymphatic system is one of the most commonly affected sites [13, 14, 15, 16]. Rarely, the breast may be affected by systemic sarcoidosis and is usually, but not exclusively, detected after the diagnosis has been established [17, 18, 19].

Given the lack of specific diagnostic biomarkers, histologic evidence of a granuloma is not uncommonly required to establish an accurate diagnosis. Granulomas are composed of tightly clustered epithelioid histiocytes, occasional multinucleated giant cells of Langhans type, and lymphocytes. An outer layer of loosely organized lymphocytes and dendritic cells is often observed. A concentric arrangement of epithelioid histiocytes around a large, multinucleated giant cell of the Langhans can also be identified. Asteroid bodies, cytoskeleton filaments, and lipoproteins located within the cytoplasm of giant cells, or Schaumann bodies, basophilic to black, concentrically laminated structures, may be seen. Necrosis is usually absent throughout the lesion. An example of systemic sarcoidosis involving the axillary lymph node and primary breast sarcoidosis of the right breast is shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

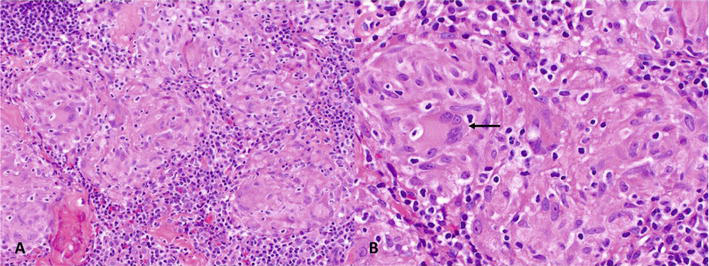

Figure 1.

Axillary lymph node involvement by systemic sarcoidosis. A–B. Histologic sections show tightly clustered epithelioid histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells of Langhans type (→). Intervening and scattered lymphocytes are small and without atypia. (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H&E], A. 20×, B. 40×).

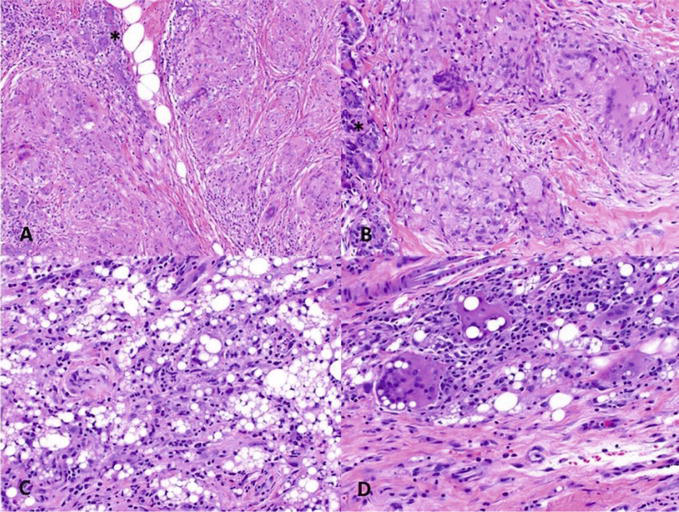

Figure 2.

Breast sarcoidosis involving the right upper-inner quadrant of a 47-year-old female. A–B. Sections show mammary parenchyma with epithelioid granulomas forming nodules with multinucleated Langhans giant cells among ducts and lobules (*). Necrosis or central microabscesses are not identified (Hematoxylin and Eosin [H&E], A. 10×, B. 20×). C-D. The differential diagnosis includes granulomatous reaction to foreign material (silicone; H&E, C. 10×, D. 20×).

The differential diagnoses of granulomatous inflammation involving the axillary lymph node or breast include infectious granulomatosis (i.e., tuberculosis, mycobacterial infection), inflammatory diseases with granulomatous reaction, drug-induced sarcoid-like reactions, or tumor-associated sarcoid-like reactions (i.e., lymphomas, carcinomas) [20].

5. Imaging

Breast sarcoidosis is a rare manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis, and its imaging features are important for diagnosis and appropriate management. The imaging characteristics of breast sarcoidosis have been studied across various modalities, and available literature provides valuable insights into this uncommon condition.

Mammography plays a crucial role in the initial evaluation of breast sarcoidosis. Reis et al. (2019) conducted a study involving 12 patients with breast sarcoidosis, where mammographic findings revealed ill-defined masses with dense, irregular margins in 83% of cases. These masses exhibited asymmetric density or focal architectural distortion which has been described as a high density mass with spiculated margins [2, 21]. Calcifications were relatively uncommon, observed in only 17% of the patients, and when present, they tended to be fine and punctate. However, it is important to note that mammographic features of breast sarcoidosis are non-specific and can overlap with other benign or malignant breast conditions, necessitating histopathological confirmation for accurate diagnosis [2].

Ultrasound is another valuable imaging modality for evaluating breast sarcoidosis. A study by Huang et al. (2010) included 14 patients with biopsy-proven breast sarcoidosis where findings demonstrated hypoechoic masses with irregular margins in 71% of the cases. Furthermore, posterior acoustic shadowing, suggesting a dense or solid nature of the masses, was observed in 79% of patients. Sarcoidosis can be seen as a solitary irregular mass, but can also be seen as multiple masses [21, 22]. In some cases, diffuse hypoechoic parenchymal changes without distinct masses have been documented. The use of a linear high frequency probe with high-resolution probe can help evaluate better the characteristic irregular margins with spiculations, and heterogenous echotexture of the classic sarcoidosis mass finding [23]. However, similar to mammography, ultrasonographic features of breast sarcoidosis are non-specific and may mimic other breast pathologies. Therefore, biopsy remains necessary for definitive diagnosis [24].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is an additional tool for evaluation of breast sarcoidosis with functional imaging features emphasizing degree of vascularity and molecular composition. In a study by Huang et al. (2010), MRI findings of 12 patients with breast sarcoidosis revealed most masses demonstrated low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. After gadolinium-based contrast administration, these masses demonstrated heterogeneous mass enhancement. However, MRI features also resemble other inflammatory or neoplastic breast conditions. Histopathological confirmation through biopsy remains necessary for definitive diagnosis [24].

Fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-computed tomography (CT) is used to detect metabolically active lesions typically in the setting of malignancy. The imaging features and patterns of sarcoidosis on FDG PET/CT varies and can mimic lymphatic cancer and metastatic disease because of the common finding of intrathoracic lymphadenopathy [25]. In general, enlarged lymph nodes with increased FDG uptake are revealed on axial plain CT, PET, and PET-CT fusion images [26, 27]. Zivin et al. (2014) report a case of a patient with known breast cancer and histologically confirmed sarcoidosis, which was initially thought to be metastatic cancer. The presence of concurrent sarcoidosis was detected on FDG PET/CT as hypermetabolic mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes in a “butterfly” distribution pattern [28]. Sarcoidosis and breast cancer have been documented to occur simultaneously, which given the relative rarity of the disease, diagnosis can often be confounded by concomitant cancer [29].

Molecular breast imaging (MBI) provides functional information about breast sarcoidosis by using Tecnecium-99 sestamibi radiotracer. Cattaneo et al. (2012) reported a case series of four patients with breast sarcoidosis who underwent MBI. The MBI findings showed areas of increased radiotracer uptake corresponding to inflammatory granulomas in all cases. However, due to its limited anatomical detail, MBI should be used in conjunction with other imaging modalities to achieve an accurate diagnosis [30].

Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM), which uses intravenous iodinated contrast agents, can enhance the visualization of breast lesions. Reis et al. (2021) studied 12 patients with breast sarcoidosis and reported that contrast-enhanced mammography revealed irregular masses with focal enhancement patterns in 67% of the cases [1]. See imaging examples in Figures 3–9.

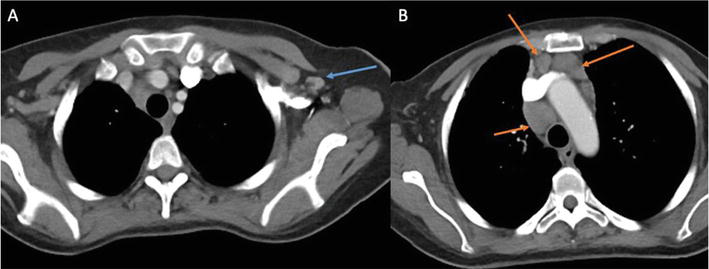

Figure 3.

Axial contrast enhanced chest CT in a patient with a known history of breast cancer. A. There is a prominent left axillary lymph node measuring 1.1 cm (blue arrow). B. Extensive multi station mediastinal adenopathy including a 2.3 cm right upper paratracheal lymph node, 2.6 cm subcarinal lymph node, 1.2 cm para-aortic node and 1.5 cm preaortic lymph node (orange arrows).

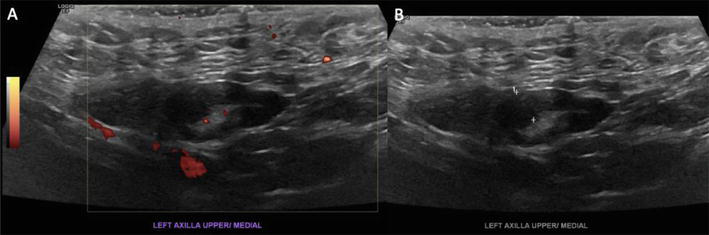

Figure 4.

Limited left axillary ultrasound. A. The Power Doppler technique showing hilar vascularity. B. An enlarged lymph node in the left axilla with cortical thickness of up to 0.5 cm.

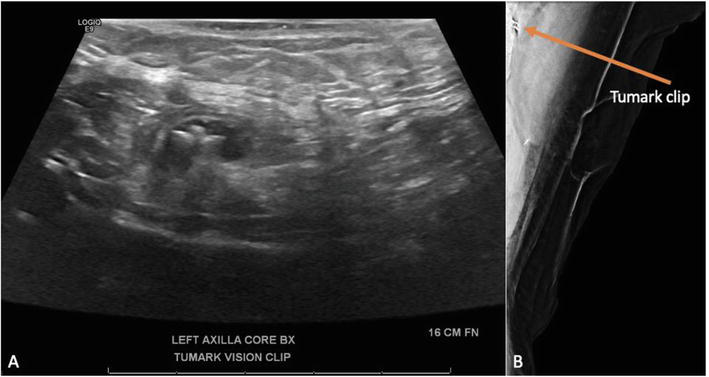

Figure 5.

Ultrasound guided core needle biopsy of enlarged left axillary lymph node. A. Several core needle biopsy passes performed followed by clip placement. B. Tumark clip shown on mammogram after biopsy.

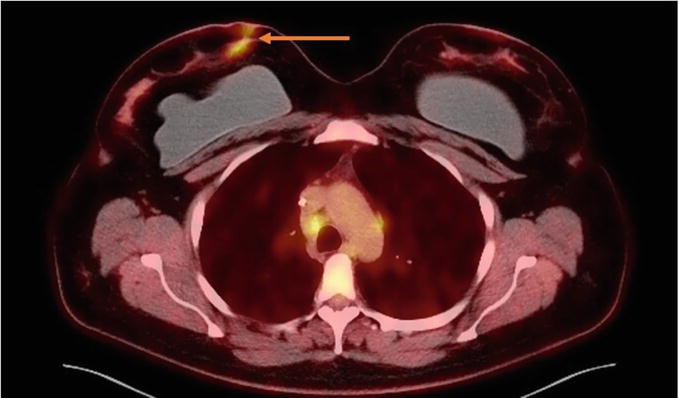

Figure 6.

Nuclear Medicine PET/CT Chest. FDG avid subcutaneous lesions noted in the upper inner right breast (orange arrow).

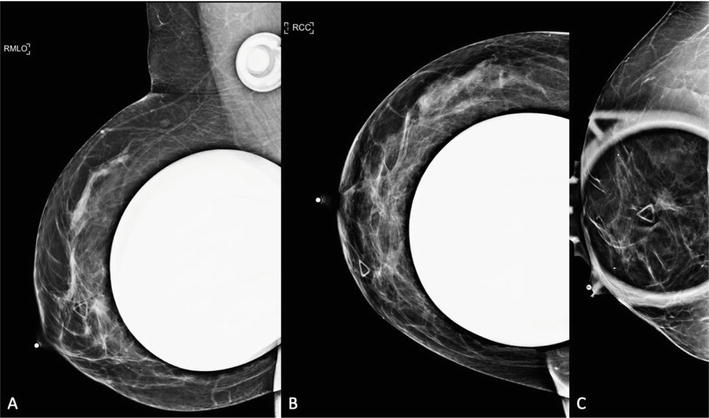

Figure 7.

Digital diagnostic cranial caudal and mediolateral oblique views of the right breast obtained with and without implant displacement. A. There is a 1.2 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm irregular, spiculated mass, superficial in location, with questionable spiculations extending to the overlying skin. B, C. An area of architectural distortion in the right outer breast, middle depth, 6 cm from nipple improves on additional spot compression views favoring tissue summation. 0.4 cm round circumscribed mass in the right retro-areolar breast. Focal asymmetry in the right upper outer breast, middle and posterior depths favoring tissue summation on tomosynthesis imaging.

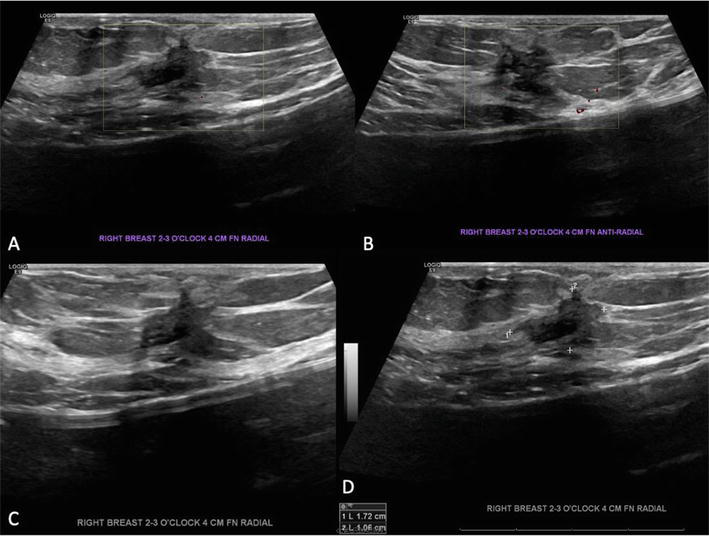

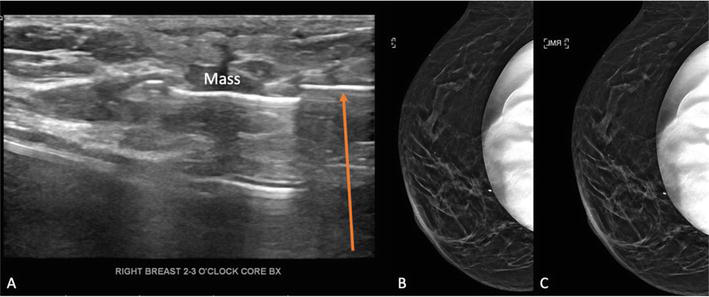

Figure 8.

Breast ultrasound. A-D 1.7 cm irregular mass correlates with PET CT FSG avid mass and mammogram finding under the palpable site and is deemed highly suspicious for breast malignancy – BIRADS 5.

Figure 9.

Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of suspicious mass in right breast. A. Core needle visualized near mass during biopsy (orange arrow). B, C. Right cranial caudal and mediolateral oblique views on mammogram demonstrate that the biopsy clip corresponds to the abnormality on the mammogram which is under the triangle marker representing the palpable area of concern.

6. Management

Sarcoidosis of the breast is managed with the purpose of removing the granulomatous tissue. Treatment options include corticosteroids, surgery, or a combination of both along with close follow-up care [6]. Standard dose corticosteroid therapy is the treatment of choice for breast sarcoidosis and should be started as soon as possible. The dosage should be tapered gradually as well [11]. Some authors advise that the adverse effects associated with long-term steroid use should be weighed against the degree of diseased tissue and functional impairment when deciding whether to treat or not [31]. An immunosuppressive therapeutic regimen is not indicated in sarcoidosis localized to the breasts, which may be related to increased risk of skin cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and infection while hospitalized [1, 5]. Surgical management is rarely implemented but can be considered in the setting of more severely symptomatic or larger disease extent [6]. Symptomatic patients can be monitored with clinical and breast imaging surveillance, usually breast ultrasound, at regular time intervals until there is complete resolution of symptoms and improvement or stability of breast finding is achieved [7].

Ultimately, multidisciplinary collaboration between the breast radiologist, the pathologist, and the primary care provider or other treating clinician is necessary to reach a prompt diagnosis, expedite management and optimize clinical outcomes.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, breast sarcoidosis presents a diagnostic challenge due to its non-specific imaging features on various modalities. The studies conducted on small cohorts of patients have provided valuable insights into the imaging characteristics of breast sarcoidosis. Mammography, ultrasound, MRI, FDG PET/CT, MBI, and CEM may all reveal characteristic findings that can suggest breast sarcoidosis in the appropriate clinical context. However, histopathological examination remains essential for definitive diagnosis and appropriate management of this rare disease.

References

- 1.

Reis J, Boavida J, Bahrami N, Lyngra M, Geitung JT. Breast sarcoidosis: Clinical features, imaging, and histological findings. The Breast Journal. 2021; 27 (1):44-47. DOI: 10.1111/tbj.14075 - 2.

Reis J, Boavida J, Lyngra M, Geitung JT. Radiological evaluation of primary breast sarcoidosis presenting as bilateral breast lesions. BMJ Case Report. 2019; 12 (7):e229591. Published 2019 Jul 27. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229591 - 3.

Jaguś D, Yafimtsau I, Mlosek RK, Jonczak L, Roszkowska-Purska K, Dobruch-Sobczak K. Sarcoidosis of the breasts – When should it be considered? A case report. Journal of Ultrasonic. 2022; 22 (89):136-139. Published 2022 Apr 27. DOI: 10.15557/JoU.2022.0022 - 4.

Judson MA. Granulomatous sarcoidosis mimics. Frontier in Medicine (Lausanne). 2021; 8 :680989. Published 2021 Jul 8. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2021.680989 - 5.

Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: Current findings and future directions. Therapeutic Advance in Chronic Disease. 2018; 9 (11):227-240. Published 2018 Aug 24. DOI: 10.1177/2040622318790197 - 6.

Grove J, Meier C, Youssef B, Costello P. A rare case of sarcoidosis involving male breast tissue. Cureus. 2022; 14 (1):e21387. Published 2022 Jan 18. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.21387 - 7.

Rhazari M, Ramdani A, Gartini S, et al. Mammary sarcoidosis: A rare case report. Annals of Medical Surgery (Lond). 2022; 78 :103892. Published 2022 May 31. DOI: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103892 - 8.

Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: Recent estimates of incidence, prevalence, and risk factors. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2020; 26 (5):527-534. DOI: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000715 - 9.

Mason C, Yang R, Hamilton R, et al. Diagnosis of sarcoidosis from a biopsy of a dilated mammary duct. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center). 2017; 30 (2):197-199. DOI: 10.1080/08998280.2017.11929584 - 10.

Ojeda H, Sardi A, Totoonchie A. Sarcoidosis of the breast: implications for the general surgeon. The American Surgeon. 2000; 66 (12):1144-1148 - 11.

Zujić PV, Grebić D, Valenčić L. Chronic granulomatous inflammation of the breast as a first clinical manifestation of primary sarcoidosis. Breast Care (Basel). 2015; 10 (1):51-53. DOI: 10.1159/000370206 - 12.

Doan T, Nguyen NT, He J, Nguyen QD. Sarcoidosis presenting in breast imaging clinic with unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. Cureus. 2021; 13 (2):e13245. Published 2021 Feb 9. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.13245 - 13.

Sikjær MG, Hilberg O, Ibsen R, Løkke A. Sarcoidosis: A nationwide registry-based study of incidence, prevalence and diagnostic work-up. Respiratory Medicine. 2021; 187 :106548. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106548 - 14.

Caplan A, Rosenbach M, Imadojemu S. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2020; 41 (5):689-699. DOI: 10.1055/s-0040-1713130 - 15.

Mañá J, Rubio-Rivas M, Villalba N, et al. Multidisciplinary approach and long-term follow-up in a series of 640 consecutive patients with sarcoidosis: Cohort study of a 40-year clinical experience at a tertiary referral center in Barcelona, Spain. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96 (29):e7595. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007595 - 16.

Bodaghi B, Touitou V, Fardeau C, Chapelon C, LeHoang P. Ocular sarcoidosis. Presse Médicale. 2012; 41 (6 Pt. 2):e349-e354. DOI: 10.1016/j.lpm.2012.04.004 - 17.

Takahashi R, Shibuya Y, Shijubo N, Asaishi K, Abe S. Mammary involvement in a patient with sarcoidosis. Internal Medicine. 2001; 40 (8):769-771. DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.769 - 18.

Fiorucci F, Conti V, Lucantoni G, et al. Sarcoidosis of the breast: A rare case report and a review. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2006; 10 (2):47-50 - 19.

Gansler TS, Wheeler JE. Mammary sarcoidosis. Two cases and literature review. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 1984; 108 (8):673-675 - 20.

El Jammal T, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Valeyre D, Sève P. Refractory sarcoidosis: A review. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2020; 16 :323-345. Published 2020 Apr 17. DOI: 10.2147/TCRM.S192922 - 21.

Naeem M, Zulfiqar M, Ballard DH, et al. “The unusual suspects”-Mammographic, sonographic, and histopathologic appearance of atypical breast masses. Clinical Imaging. 2020; 66 :111-120. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.04.039 - 22.

Ishimaru K, Isomoto I, Okimoto T, Itoyanagi A, Uetani M. Sarcoidosis of the breast. European Radiology. 2002; 12 (Suppl. 3):S105-S108. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-002-1627-4 - 23.

Kenzel PP, Hadijuana J, Hosten N, et al. Boeck sarcoidosis of the breast: mammographic, ultrasound, and MR findings. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1997; 21 (3):439-441. DOI: 10.1097/00004728-199705000-00018 - 24.

Huang C, Chang YC, Huang WY, et al. Breast sarcoidosis: Mammographic, sonographic, and MRI findings. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2010; 38 (5):262-266. DOI: 10.1002/jcu.20689 - 25.

Prabhakar HB, Rabinowitz CB, Gibbons FK, O’Donnell WJ, Shepard JA, Aquino SL. Imaging features of sarcoidosis on MDCT, FDG PET, and PET/CT. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2008; 190 (3 Suppl):S1-S6. DOI: 10.2214/AJR.07.7001 - 26.

Li YJ, Zhang Y, Gao S, Bai RJ. Cervical and axillary lymph node sarcoidosis misdiagnosed as lymphoma on F-18 FDG PET-CT. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2007; 32 (3):262-264. DOI: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000255268.64309.8e - 27.

Akaike G, Itani M, Shah H, et al. PET/CT in the diagnosis and workup of sarcoidosis: Focus on atypical manifestations. Radiographics. 2018; 38 (5):1536-1549. DOI: 10.1148/rg.2018180053 - 28.

Zivin S, David O, Lu Y. Sarcoidosis mimicking metastatic breast cancer on FDG PET/CT. Internal Medicine. 2014; 53 (21):2555-2556. DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.3333 - 29.

Altınkaya M, Altınkaya N, Hazar B. Sarcoidosis mimicking metastatic breast cancer in a patient with early-stage breast cancer. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2015; 32 (1):71-74. Published 2015 Jul 6. DOI: 10.5152/UCD.2015.2989 - 30.

Cattaneo E, Lippolis PV, Gasparini E, et al. Breast sarcoidosis: Imaging features of a rare disease. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2012; 199 (1):W112-W116. DOI: 10.2214/AJR.11.7179 - 31.

Endlich JL, Souza JA, Osório CABT, Pinto CAL, Faria EP, Bitencourt AGV. Breast sarcoidosis as the first manifestation of the disease. The Breast Journal. 2020; 26 (3):543-544. DOI: 10.1111/tbj.13560