1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a group of genetic diseases that are associated with tumors that develop in the cutaneous and nervous systems. There are three types of neurofibromatosis that are each associated with unique signs and symptoms [1, 2, 3].

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) also known as von Recklinghausen disease causes skin changes (cafe-au-lait spots, freckling in armpit and groin area); bone abnormalities; optic gliomas; and tumors in the nerve tissue or under the skin. Signs and symptoms are usually present at birth. NF1 is the most common neurofibromatosis [1].

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) causes acoustic neuromas; hearing loss; ringing in the ears; poor balance; brain and/or spinal tumors; and cataracts at a young age [4].

Schwannomatosis (NF3) presents with schwannomas, pain, numbness, and weakness; it is the rarest type of NF [3].

All three types of NF are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner [1].

Every chapter in “Neurofibromatosis

2. Types of NF

NF is a rare genetic disorder. NF1 was originally characterized as the triad of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone, precocious puberty, café-au-lait skin pigmentation, and associated endocrinopathies including hyperthyroidism, growth hormone excess, FGF23-mediated phosphate wasting, and hypercortisolism [1]. NF2 classically involves the nervous system

The three types of neurofibromatosis (NF) are all proliferative disorders that are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, can involve cutaneous sites (skin), the nervous system or gastric tissues, and remain a medical challenge [1]. Although there have been significant improvements in responses with the use of target-directed therapies in recent years, surgery and radiation remain the primary approaches to the management of NF. Advanced unresectable NF is commonly ‘resistant to systemic therapies’ because of the lack of knowledge regarding best mechanism(s) for drugs to penetrate the proliferative membranes [6, 7, 8, 9].

3. History

Records and reports of neurofibromatosis, as we currently appreciate the condition, were reported centuries ago [1]. The tumors and condition were first known as von Recklinghausen disease, the first person to describe NF [1]. There has been a slow improvement in the therapeutic approaches to the types of NF. The latter might only be associated with the improved quality of life available through support care only.

4. Histology

NF1 is usually associated with mutations on chromosome 17 with encoding of a cytoplasmic protein—neurofibromin. Neurofibromin is a tumor suppressor protein and regulator of cell proliferation signaling and differentiation. Neurofibromatosis (NF1) is a result of dysfunction or lack of neurofibromin, resulting in uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor development (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1.

Example of NF1.

The most common forms of NF are observed in the skin and nervous systems. NF1 or von Recklinghausen’s disease is an autosomal disorder (caused by a loss of function mutation, either

NF1 tumors are usually benign arising from supporting Schwann nerve cell tissues but cause neurological damage by compressing nerves and other tissues [1].

NF type 2 (NF2) has an autosomal dominant genetic pattern (a loss of function mutation on chromosome 22). The mutation involves the Schwann cell genetic encoding of a cytoplasmic protein—Merlin [8]. Merlin regulates multiple growth factors, and its absence or during NF2 gene mutations, there are formation of tumors—vestibular schwannomas and meningiomas.

The latter results in bilateral acoustic neuromas involving the vestibulocochlear nerve or cranial nerve 8 and loss of hearing [8].

Schwannomatosis (NF3) has only recently been classified as a neurofibromatosis and involves mutations on Schwann cell SMARCB1 genes, resulting in spinal and peripheral nerve tumors in the perineal area [1]. The SMARCB1 gene and the chromosome 22 are different gene sites; however, mutations in both genes result in NF3 tumors. The SMARCB1 gene is located near the NF2 tumor suppressor gene, and thus, the original thoughts were that they were the same disease; the latter concept has been reversed [9].

5. Epidemiology

NF1 involves about 96% of all neurofibromatosis cases. Prevalence is 1 in 3000 births. It occurs equally between gender and races. Fifty percent (50%) of patients have a spontaneous mutation, and the other half have an inherited mutation. NF2 makes up about 3% of all cases and has a prevalence between 1 in 33,000 births with the disorder. The damage to nearby vital structures such as cranial nerves and brain tissue can be life treating [1].

NF3 is the rarest of the group (<1% incidence), and typically life expectancy is not affected in the latter patients with Schwannomatosis [1].

NF1 is the most common of the NF types and may be ‘increasing in occurrence’, but knowledge and management skills with the disease have improved, and presentations of the disease are not as prevalent; however, debilitation still exists—as noted above. Overall, long-term responses for NF have improved [1].

However, there remains a paucity of useful therapeutic tools and best approaches to therapy for pediatric and adolescent patients with NF involving the CNS, whom are otherwise healthy, but are seldom referred for clinical trials with novel new agents because they are <18 years of age.

6. Therapy: current and new

The neurofibromas that develop are usually initially benign, and surgical removal is optional—cosmetic, symptomatic, etc. However, for any neurological changes, new developments in sizes or progression to a malignant stage, a referral to a neurologist and/or surgeon is important [10, 11].

Treatment may include surgery, focused radiation, or chemotherapy. Acoustical and optic tumors may cause communication impairment and are often electively surgically removed. Monitoring for new signs of progressive neurological deterioration is mandatory, especially in the pediatric and adolescent aged group. Cataracts must be a considered a risk for all ages. Assessment for hearing impairment must be monitored for all ages [1, 2, 3].

Plexiform neurofibromas have malignant potentials (8–13% risk) and must be monitored closely—malignant tumors can develop peripherally in nerve sheaths [7].

Radiation can be used, but there is increased risk of malignant transformation [1].

Surgery to remove NF2 tumors completely is one option. Surgery for vestibular schwannomas does not restore hearing and usually reduces hearing. Sometimes surgery is not performed until functional hearing is lost completely. Surgery may result in damage to the facial nerve resulting in some degree of facial paralysis. Focused radiation of vestibular schwannoma is associated with a lower risk of facial paralysis than open surgery, but is more effective in shrinking small to moderate tumors than larger tumors [4, 8, 9, 10].

Chemotherapy with a drug that targets the blood vessels of vestibular schwannoma can reduce the size of the tumor and improve hearing, but some tumors do not respond at all, and responses are only temporary. Bone malformations can be corrected surgically, and surgery can also correct cataracts and retinal abnormalities. Pain usually subsides when tumors are removed completely [6, 9, 11].

In April 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved selumetinib (Koselugo) as a treatment for children ages 2 years and older with NF1. The drug helps to stop tumor cells from growing [11].

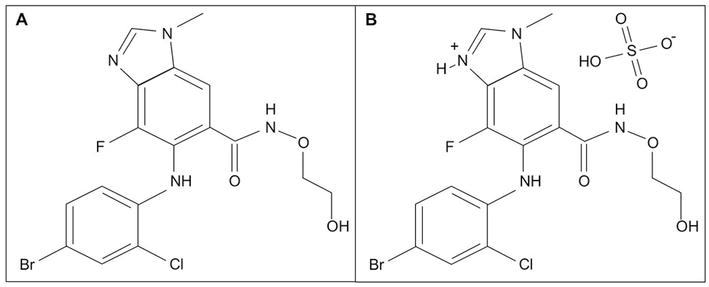

Selumetinib (Figure 2) is a kinase inhibitor that is a selective inhibitor of the enzyme mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK kinase or MEK) subtypes 1 and 2. These enzymes are part of the MAPK/ERK pathway, which regulates cell proliferation (

Figure 2.

A. Selumetinib (Koselugo) & B. Sulfate salt.

Imatinib mesylate has also been approved as treatment for plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: a phase 2 trial [7, 11].

All drugs being used possess bio-releasable reactive halogenated moieties that could interact with DNA and interfere with genetic replication [7, 11].

In summary, the core therapeutic challenges to obtaining long-term objective responses include

Transport of drugs into the tumor sheaths

Although the use of protocols that include tumor target markers is becoming popular, the penetration of neurofibromas is still an issue.

For focal lesions, surgical resection followed by chemotherapy plus radiation

The absence of Merlin protein is an issue. Studies with Merlin are of major interest for future clinical trials.

Developing new drugs that are small or have unique transport mechanism(s)

Identifying surface receptors on the affected nerve sheaths will assist with drug transport into the NFs.

7. Conclusion

This has been an attempt to review the history, pathology, and treatments available for neurofibromatosis. Minimal information is available regarding chemotherapy for the types of NF that are known; however, clinical trials are in progress worldwide. The positive responses observed and reported to date are support for continued clinical trials in neurofibromatosis.

Interesting chapters are presented in this book that review some of the progress being made that will allow improved management for this disease.

References

- 1.

Kresak JL, Walsh M. Neurofibromatosis: A review of NF1, NF2, and Schwannomatosis. Journal Pediatrics and Genetics. 2016; 8 :234 - 2.

Ruggieri M, Iannetti P, Polizz A, et al. Earliest clinical manifestations and natural history of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) in childhood: A study of 24 patients. Neuropediatrics. 2005; 36 :21-34 - 3.

MacCollin M, Chiocca EA, Evans DG, et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2005; 64 :1838-1845 - 4.

Evans DG. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2): A clinical and molecular review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2009; 4 :16 - 5.

Mathieu D, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: An analysis of tumor control, complications, and hearing preservation rates. Neurosurgery. 2007; 60 :460-470 - 6.

Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Achieves of Neurology. 1988; 45 :575-578 - 7.

Robertson KA, Nalepa G, Yang FC, Bowers DC, Ho CY, Hutchins GD, et al. Imatinib mesylate for plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: A phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012; 3 :1218-1224 - 8.

Plotkin SR, Merker VL, Halpin C, et al. Bevacizumab for progressive vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2: A retrospective review of 31 patients. Otology & Neurotology. 2012; 33 :1046-1052 - 9.

Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, Moss C, Willshaw H, Evans DG, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007; 44 :81-88 - 10.

Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: A multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurology. 2014; 13 :834-843 - 11.

Anderson MK, Johnson M, Thornburg L, Halford Z. A review of Selumetinib in the treatment of Neurofibromatosis type 1—Related plexiform Neurofibromas. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2022; 56 :716