Abstract

In recent years, highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza has occasionally plagued wild bird populations. For the first time in 2022, it was particularly virulent on the gull populations of the Hauts-de-France coast (France). This work analyzes the consequences of the virus on the numbers and production of young in three colonies of gulls (Laughing Gull, Mediterranean Gull, and Sandwich Tern) on the coast of Pas-de-Calais and the Somme by comparing with the results of the years previous pandemic-free periods. This work also compares the numbers of roosts of several species of gulls in the Authie-Somme reserve obtained in spring to autumn in 2022 with those of previous years.

Keywords

- highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza

- gull populations

- Hauts-de-France

- pandemic

- gull mortality

1. Introduction

Cases of joint mass mortalities involving humans, domestic mammals, and birds have been known since antiquity (1200 BC) but scientific evidence that it is avian influenza does not appear until the end of the nineteenth century [1].

For many decades, wild birds, especially ducks, have been known to be healthy carriers of various influenza viruses.

The H5N1 strain was detected in a few geese in 1996 in China and then the following year in Hong Kong, where it affected humans and chicken farms [1].

A new emergence of this strain occurs in 2004 in East Asia. It spread the following year to Turkey and Romania and then reached Western Europe in 2006 (including France). Another wave was reported in 2015 with cases recorded, particularly in Africa and North America [2].

The role of migratory birds in the dispersal of H5N1 has been the subject of numerous studies [3, 4, 5, 6] as has its impact on poultry farms [7, 8, 9, 10], but the one on wild birds remains unknown.

For the first time in 2022, this H5N1 strain was particularly virulent in the gull populations of Hauts-de-France (France). Also, an attempt to measure the influence of this virus on these birds was made. This work analyzes the consequences of the virus on gull mortality, breeding numbers, and the production of young in three colonies (Black-headed Gull

2. Methods

Gull corpses were counted at the various sites studied.

The colonies of three localities of Marquenterre (Ornithological Park of Marquenterre in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont in the Somme, Conchil-le-Temple, and Groffliers in the Pas-de-Calais) were counted at least once per decade of March to July. No incursion is carried out on the colonies which are observed from a distance (from observation posts in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont and Conchil-le-Temple). Whenever possible, breeding adults were distinguished from nonbreeding immature. Behaviors related to reproduction (copulations, transport of materials, and incubating nests) were also noted. As soon as they appear, the chicks are also counted. The species concerned are the Black-headed Gull, the Mediterranean Gull, and the Sandwich Tern.

In the Authie-Somme reserve, gull roosts are counted or estimated (in the case of numbers of several thousand individuals of a single species) throughout the annual cycle. Rare taxa (Bonaparte’s Gull

In both types of data, the numbers of the years without the emergence of the H5N1 virus (2018 to 2021) are compared to those of the year with the virus. Due to COVID-related traffic restrictions, data from mid-March to early May 2020 was sometimes not obtained.

3. Results

The first gull victim of H5N1 is an immature Herring Gull

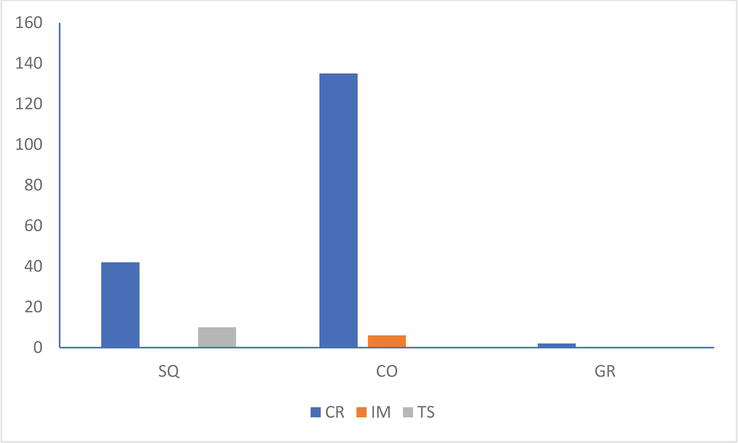

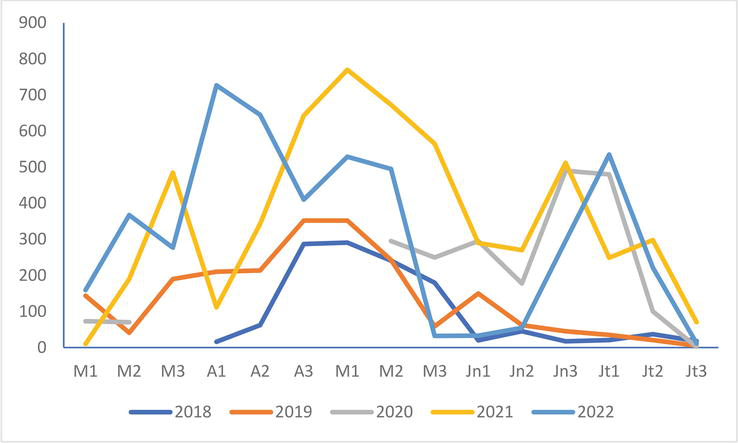

Of the three colonies studied, it was mainly the corpses of Black-headed Gulls (Figure 1) that were discovered (179 for 6 Mediterranean Gulls and 10 Sandwich Terns).

Figure 1.

Number of black-headed Gull

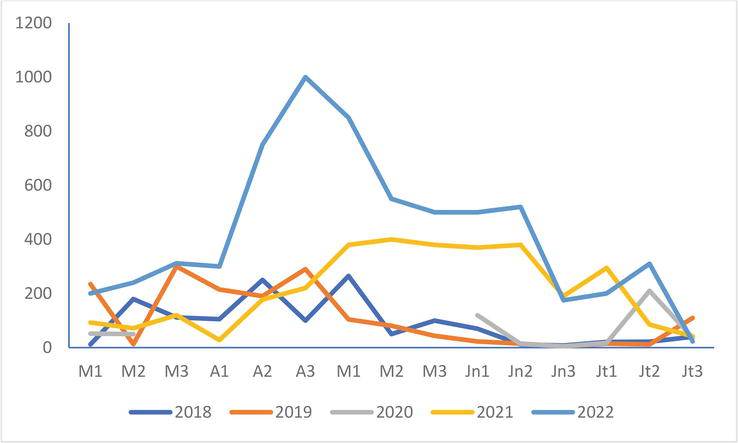

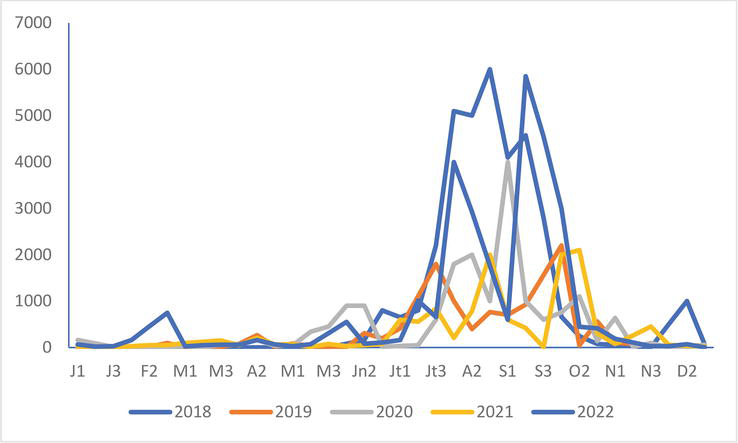

During the study period, the Black-headed Gull colony at Conchil-le-Temple is expanding with numbers at the end of April 2022, ten times higher than those of 2018 and more than three times those of 2019 and 2021 (Figure 2). These numbers fall in May to reach a minimum at the end of June, slightly lower than those of 2021 during the same period but nevertheless remain significantly higher than those of the first three years studied.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the numbers of the black-headed Gull

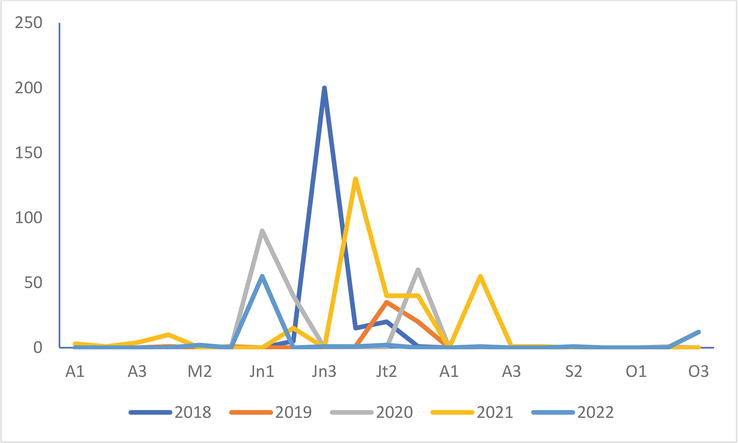

The situation of the colony of Groffliers is different since the maximum number in 2022 is between the minimum recorded in 2018 and the maximums of 2019, 2020, and 2021 (Figure 3). However, they show an earlier (early May) and faster fall than those of these 4 years.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the numbers of the black-headed Gull

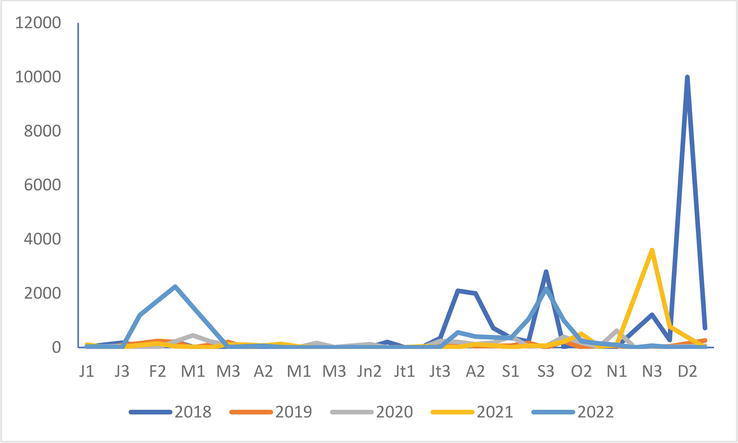

The situation of the colony of Saint-Quentin (Figure 4) is like that of Conchil-le-Temple since the numbers at the end of April are significantly higher than those of the 3 years for which data are available during this decade (2018, 2019, and 2021). They drop to a minimum in mid-June, barely higher than those of 2018 and 2020 but lower than those of 2019 and 2021. These 2022 numbers increase again from the end of June.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the numbers of the black-headed Gull

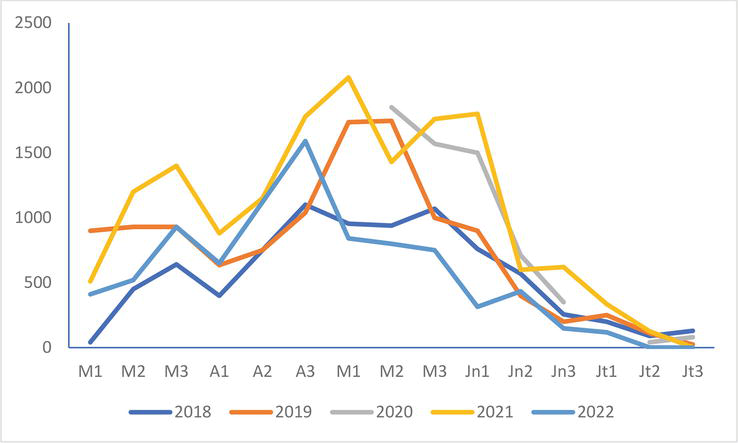

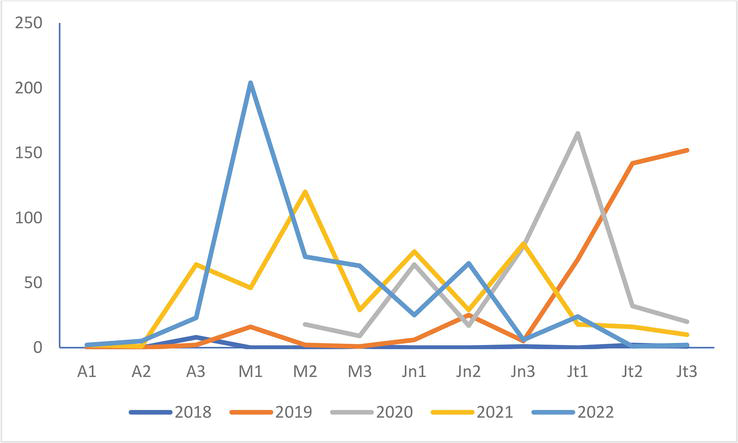

The numbers of the Mediterranean Gull colony in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont are high at the beginning of April and higher than those of the years 2018, 2019, and 2021 and of the same order of magnitude as those of the first two decades of May 2021, but they drop sharply from the end of May, remain very low until mid-June before increasing until the beginning of July (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Evolution of the numbers of the Mediterranean Gull

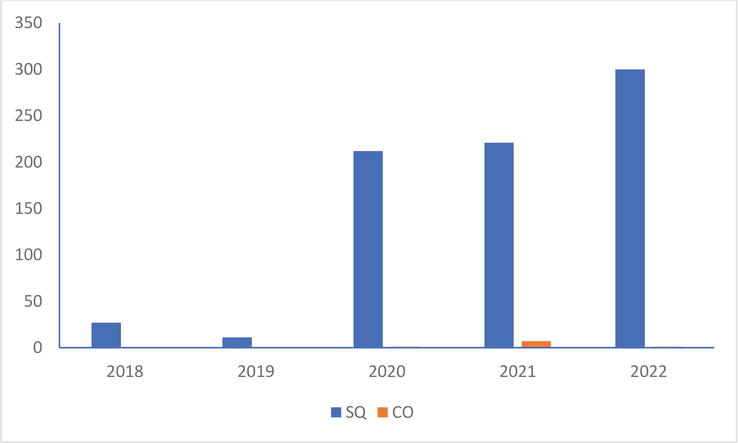

The Sandwich Tern colony in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont has been expanding since 2019. Its numbers at the beginning of May 2022 seem to confirm this fact since they are a little less than five times higher than those of 2021 (Figure 6). They show a very clear decrease from the following decade to be at the level of those of 2020 and 2021. This is even more significant with numbers lower than those of the three previous years in July.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the numbers of the Sandwich tern

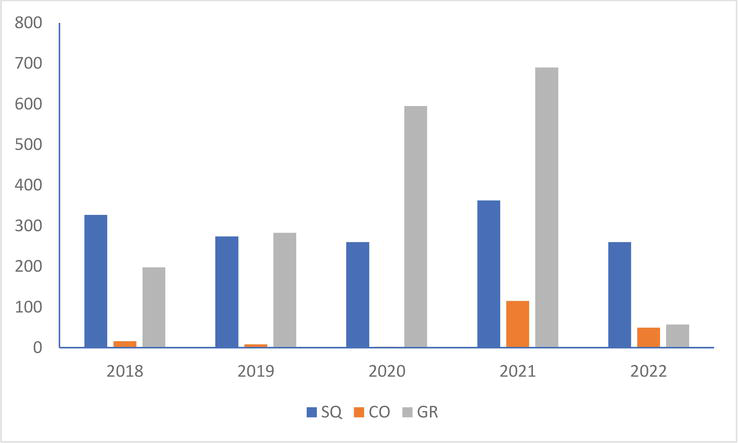

In the Black-headed Gull, the production of young in 2022 is lower than that of the four previous years in the colonies of Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont and Groffliers while on that of Conchil-le-Temple it is only lower than that of 2021 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Number of young black-headed Gull

In the Mediterranean Gull, the production of young in 2022 is higher than that of the four previous years in the colony of Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont (Figure 8). It is very low on that of Conchil-le-Temple: 1 young noted in 2020 and 2022 but 7 in 2021.

Figure 8.

Number of young Mediterranean Gull

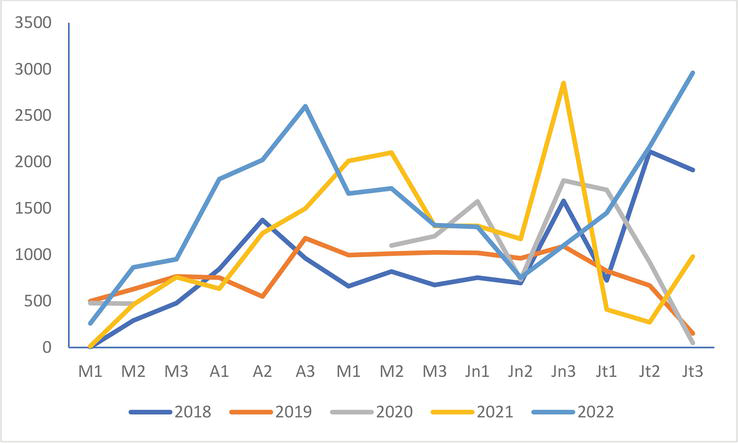

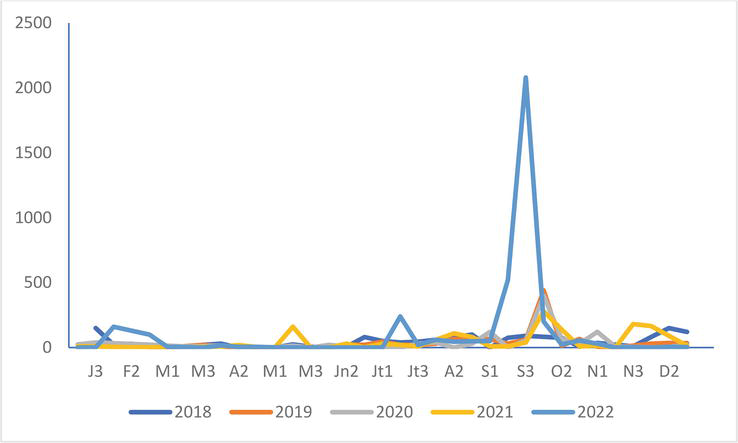

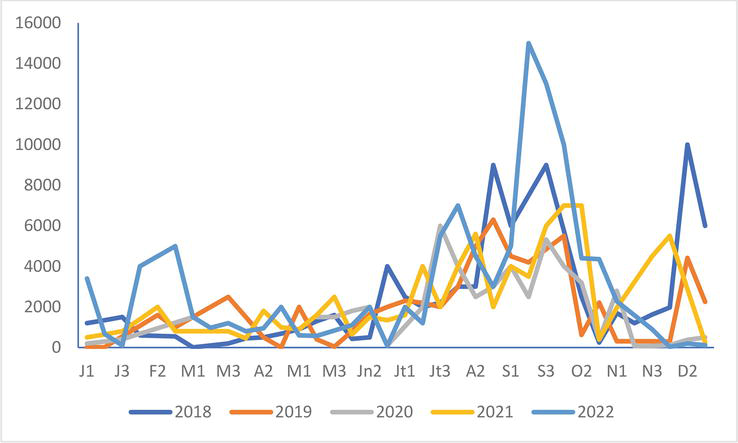

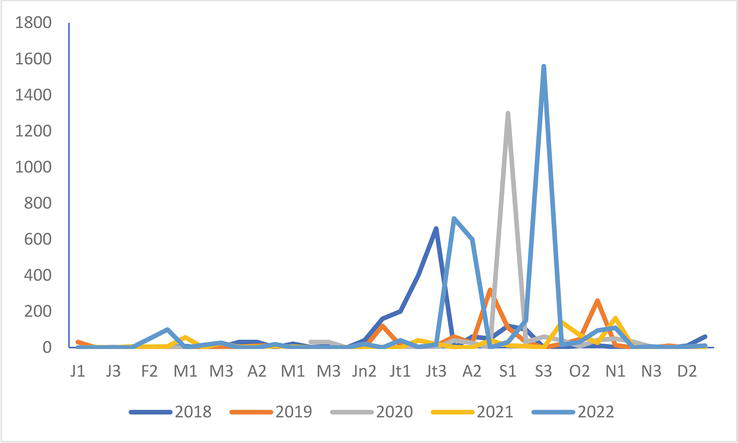

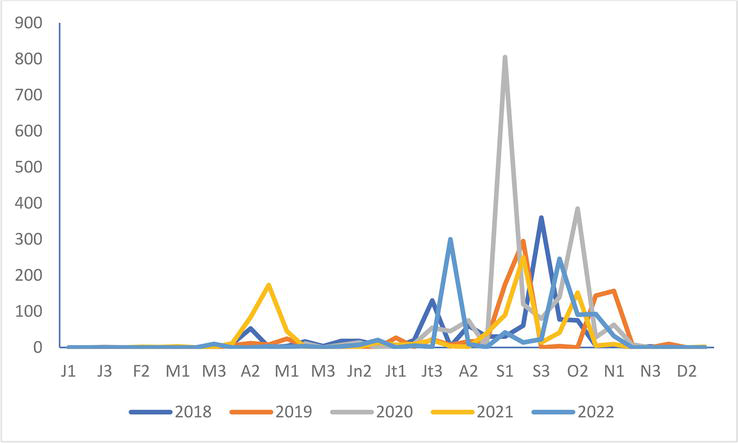

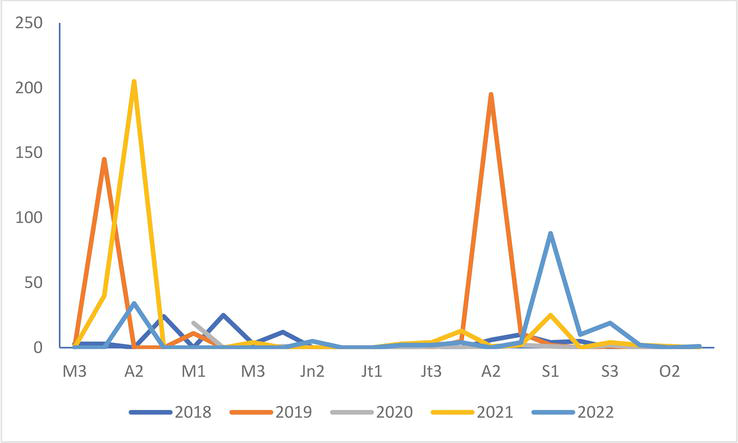

In the Authie-Somme Reserve, the differences in numbers from the years 2018 to 2022 do not appear clearly in the Black-headed Gull (Figure 9), Common Gull

Figure 9.

Black-headed Gull

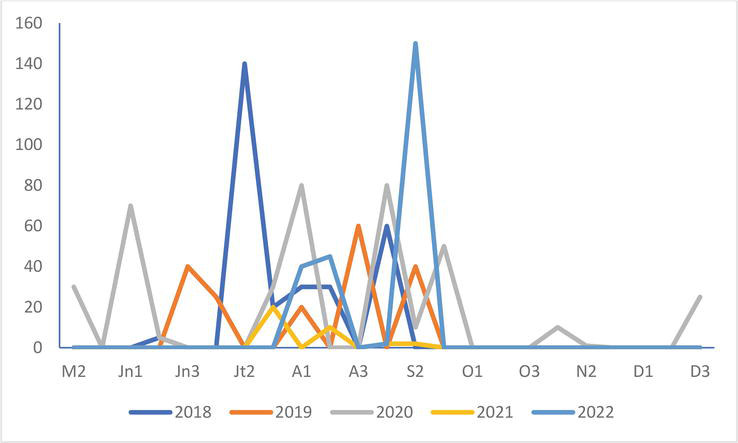

Figure 10.

Mediterranean Gull

Figure 11.

Common Gull

Figure 12.

Great black-backed Gull

Figure 13.

Herring Gull

Figure 14.

Yellow-legged Gull

Figure 15.

Lesser black-backed Gull

Figure 16.

Sandwich tern

Figure 17.

Numbers of common tern

4. Discussion

The mortality of gulls in the study area is most likely underestimated because collections of dead birds were carried out in the Authie-Somme Reserve and the Somme Bay National Nature Reserve by the municipal services of the communes concerned and by the agents of the OFB (Office Français de la Biodiversité), and on the site of the Marquenterre Ornithological Park and the estuary part of the Somme Bay National Nature Reserve by the staff of these structures. Another source of underestimation is the relatively high vegetation in at least certain sectors of the colonies of Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont, Conchil-le-Temple, and even more of Groffliers.

The H5N1 virus markedly affected the size of the three colonies and their production of young in the Black-headed Gull. The same is true for the Sandwich Tern in Saint-Quentin-en-Tourmont. However, on this site, the case of the Mediterranean Gull is more complex since the size of the colony is decreasing but the production of young increases in 2022 compared to the four previous years. This fact is probably related to the lower mortality of the Mediterranean Gull compared to that of the other two species (Figure 1). To identify the longer-term impact of the virus, it is planned to continue the census of the three colonies studied.

In the Authie-Somme Reserve, where significant mortality was observed from mid-May to June in particular, significant decrease following the emergence of H5N1 could not be demonstrated (except in the Mediterranean Gull) probably due to the massive arrival and prolonged stay of migrants. The very large numbers recorded according to the species between the beginning of August and mid-October are perhaps caused by a strong increase in the densities of the gulls’ prey [11] less consumed by the latter during part of their reproduction period (May and June) [12].

This work constitutes the first approach to the impact of H5N1 on gull populations. Given the dynamics of the colonies and the significant interannual fluctuations in the numbers, it will be necessary to obtain larger annual series to be able to carry out statistical analyses.

References

- 1.

Blancou J. Histoire de la surveillance et du contrôle des maladies animales transmissibles. Paris: Office international de épizooties; 2000. p. 366 - 2.

Peyre M, Gaidet N, Caron A, Cappelle J, Tran A, Roger F. Influenza aviaire dans le monde: situation au 31 janvier 2015. Bulletin Epidémiologique – Santé animale, Alimentation. 2015; 6 :10-14 - 3.

Gauthier-Clerc M, Lebarbenchon C, Thomas F. Recent expansion of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1: A critical review. Ibis. 2007; 149 :202-214 - 4.

Weber TP, Stilianakis NI. Migratory birds, the H5N1 influenza virus and the scientific method. Virology Journal. 2008; 5 :57-59 - 5.

Caron A, Gaidet N, de Garine-Wichatitsky M, Morand S, Cameron EZ. Evolutionary biology, community ecology and avian influenza research. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2009; 9 :298-303 - 6.

Takekawa JY, Prosser DJ, Newman SH, Muzaffar SB, Hill NJ, Yan B, et al. Victims and vectors: Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 and the ecology of wild birds. Avian Biology Research. 2010; 3 :1-23 - 7.

Kayali G, Ortiz EJ, Chorazy ML, Gray GC. Evidence of previous avian influenza infection among US Turkey workers. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2009:1-8 - 8.

Akanbi OB, Taiwo VO. Husbandry practices and outbreak features of natural highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) in Turkey flocks in Nigeria, 2006-2008. JWPR. 2015; 5 :109-114 - 9.

Liu H, Zhou X, Zhao Y, Zheng D, Wang J, Wang X, et al. Factors associated with the emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza a (H5N1) poultry outbreaks in China: Evidence from an epidemiological investigation in Ningxia, 2012. Transboundary Emerging Diseases. 2015:1-8 - 10.

Kammon A, Doghman M, Eldaghayes I. Surveillance of the spread of avian influenza virus type a in live bird markets in Tripoli, Libya, and determination of the associated factors. Veterinary World. 2022; 15 :1684-1690 - 11.

Sueur F. Stratégies d'utilisation de l'espace et des ressources trophiques par les Laridés sur le littoral picard. Rennes: Thèse Doctorat Université Rennes; 1993. p. 119 - 12.

Dabouineau L, Ponsero A. Synthesis on biology of common European cockle Cerastoderma edule. HAL. 2011:1-23