Abstract

Hiatal hernia is a protrusion of abdominal organs through enlarged esophageal hiatus. Hiatal hernia is a relatively common pathology but, in most cases, it remains asymptomatic. Four types of hiatal hernia exist. Type I or sliding hernia, type II or true paraesophageal hernia, type III or mixed hernia and type IV or giant hernia. Diagnosis of hiatal hernia usually is done by upper endoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium examination. Treatment of hiatal hernia type I coincides with concomitant gastroesophageal reflux treatment, while treatment of hiatal hernia type II, III and IV is mainly surgical. The surgical approach to repair hiatal hernia could be either transabdominal or transthoracic. Currently, laparoscopy is the best method for hiatal hernia repair. Surgery consists of two main steps: hiatal hernia plasty and fundoplication. Despite modern technologies the recurrence rate in large hiatal hernia repair remains high, therefore reinforcement of the diaphragm with mesh is recommended. There are controversies about the materials and techniques used.

Keywords

- hiatal hernia

- paraesophageal hernia

- diaphragmatic hernia

- fundoplication

- laparoscopic surgery

1. Introduction

Hiatal Hernia (HH) is a protrusion of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity through an enlarged esophageal hiatus. Most HH are asymptomatic, therefore the exact incidence of HH is difficult to determine. It is estimated that HH prevalence in western populations is about 15 to 20% [1]. Risk factors for HH are obesity, elevated intra-abdominal pressure and increasing age. The pathogenesis of HH is still not very clear [2]. Four types of HH are defined by gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and stomach localization. Type I or sliding hernia when GEJ “migrates or slides off” into the mediastinum, type II or true paraesophageal hernia—when GEJ is intra-abdominal, but stomach fundus is above diaphragm, type III is mixed hernia—the combination of the previous two types and type IV is giant hernia. Type I (sliding) of HH is the most common type, involving about 90–95%. HH type I is mostly asymptomatic. If symptoms exist, they coincide with concomitant Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) symptoms. Treatment of HH type I is based on GERD treatment and indication for surgery depends on GERD. HH type II, III and IV are Paraesophageal Hernias (PEH) and are more dangerous than type I because of the possibility of strangulation. They are estimated to occur in only 5–10% of all HH cases [3]. Symptoms of PEH are connected not only with GERD symptoms, but also with the hernia volume effect on intrathoracic organs—the respiratory system, cardiovascular system and the esophagus. The patient could complain of dysphagia, dyspnea, or arrhythmias etc. However, many PEH are without symptoms—it is estimated that only about 50% of PEH are symptomatic [4]. Surgery is usually indicated in symptomatic PEH. Laparoscopic transabdominal access is currently the best option for HH repair. Even huge PEH can be operated laparoscopically with good results, controversies exist regarding surgical methods and materials. This chapter summarizes the latest information about surgical treatment of HH.

2. Classification

Hiatal hernias (HH) are divided into four types:

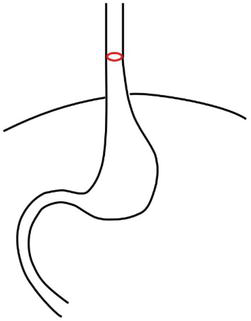

Type I (sliding HH) – characterized by displacement of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) > 2 cm above the diaphragm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hiatal hernia type I. GEJ (red) is above the diaphragm.

This type of HH is seen most in clinical practice.

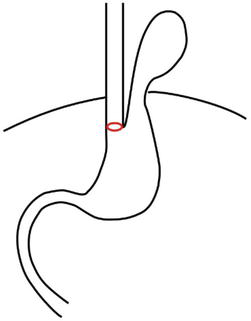

Type II (true paraesophageal hernia) – is characterized by a defect in the Phrenoesophageal Membrane (PEM) where the gastric fundus migrates above the diaphragm. In this pathology, the GEJ remains in its correct intra-abdominal position (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hiatal hernia type II. GEJ (red) is below the diaphragm.

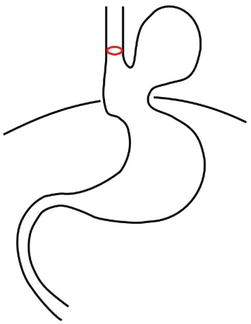

Type III (mixed paraesophageal hernia) – is characterized by a combination of both previous types—type I and type II. In this situation, both the GEJ and the gastric fundus (or body and even antrum—depending on HH size) migrate above the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hiatal hernia type III.

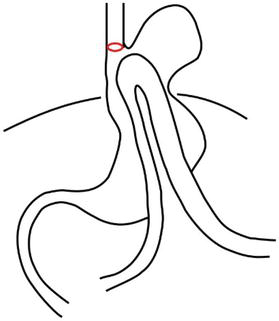

Type IV (giant paraesophageal hernia) – is characterized by a large defect in the PEM, where not only is the stomach located above the diaphragm, but also other intra-abdominal organs (e.g., the colon, spleen, pancreas and small intestines etc.) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hiatal hernia type IV.

Types II, III and IV are also named as paraesophageal hernias (PEH). HH type I and PEH differ in clinical presentation, complications and in management.

3. Clinical presentation

3.1 Sliding hiatal hernia (type I)

HH type I is often asymptomatic and found incidentally. If symptoms exist, they are associated with symptoms of GERD and could be categorized into typical and atypical symptoms.

Typical symptoms are heartburn, regurgitation, water brush, chest pain, dysphagia, belching and bloating. The most common signs are heartburn and regurgitation. Heartburn is described as a retrosternal burning sensation and refers to most specific symptoms of GERD. Regurgitation is described as food or gastric juice coming up from the stomach. GERD could cause erosions and ulcers in the esophagus. Chronic inflammation led to peptic strictures and Barrett’s esophagus (when normal esophageal epithelium is replaced with metaplastic columnar cells). Patients with Barrett’s esophagus have a higher risk of esophageal cancer development.

Atypical or extra-esophageal symptoms are hoarseness, throat pain, chronic cough, shortness of breath, asthma and dental erosion. The main reason for respiratory extra-esophageal symptoms is microaspiration of gastric content during reflux episodes. Dental erosions are the result of chemical irritation of the enamel by gastric acid [5]. Extra-esophageal symptoms are much more difficult to identify and diagnose because they could also have other causes, such as from pulmonary, dietary, or allergic conditions. Moreover, extra-esophageal symptoms do not often decrease with proton pump inhibitor therapy and can lead to other complications [6]. Therefore, if such symptoms cannot be explained by other pathology than GERD, it is an indication to proceed with surgical treatment.

3.2 Paraesophageal hiatal hernias (type II, III, IV)

PEH can be asymptomatic and have intermittent or constant symptoms. Most common symptoms of PEH are postprandial retrosternal pain, epigastric pain, fullness, retching, nausea, regurgitation. On the other hand, specific GERD symptoms like heartburn are less common. Compression of the mediastinum by an intrathoracic stomach can cause cardiac dysfunction—e.g., arrhythmias and respiratory dysfunction—dyspnea.

PEH can lead to acute problems due to mechanical obstruction in the stomach. The most common of such complications are:

Gastric volvulus – which occurs with large hiatal hernias, and can cause dysphagia, obstruction and even strangulation of the stomach with necrosis. Clinical signs are severe acute retrosternal or epigastric pain and vomiting [7].

Bleeding – usually from gastric erosions or ulcers caused by mechanical compression of the diaphragm. This pathology has a specific term—Cameron Lesions. A Cameron Lesion is an ulcer, localized to the gastric body mucosa in patients having PEH. It can cause acute upper GI bleeding or chronic GI bleeding with iron-deficiency anemia [8].

4. Diagnostic workup

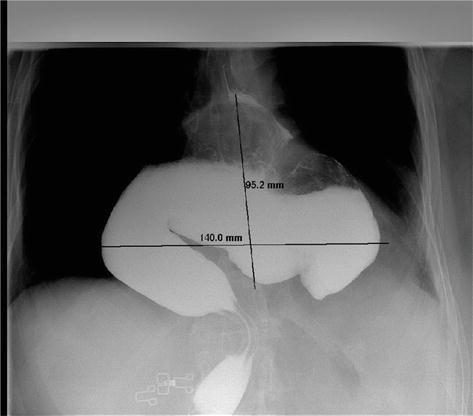

The main option for HH diagnosis is barium swallow (Figure 5). This method provides the highest rate of hiatal hernia detection [9]. The method is very useful in clinical practice because of its simplicity and wide accessibility.

Figure 5.

Barium swallow shows large PEH with intrathoracic stomach localization.

Other diagnostic options include upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, Computed Tomography (CT), manometry and pH-metry.

Upper GI endoscopy is the obligatory diagnostic tool prior to hiatal hernia surgery. It provides visualization of mucosa in the esophagus and stomach, evaluation of possible lesions and defects. Biopsy helps to differentiate benign and malignant lesions as well as dysplasia or metaplasia. Unfortunately, recent studies show that upper endoscopy has less sensitivity for HH diagnosis and false positive results lead to overdiagnosis because of stomach distention during endoscopy [10].

Computed tomography is a good option to evaluate anatomical landmarks, size and position in PEH (Figure 6). CT images allow access to other pathologies outside PEH—e.g., masses in the thoracic and the abdominal cavity. CT helps to differentiate PEH from other pathologies, especially in symptomatic hernias. Although CT is not involved in standard workup, it is frequently used as an additional option prior to surgery [11]

Figure 6.

Computed tomography of the PEH (3 projections). Most parts of the stomach are located above the diaphragm.

High-Resolution Esophageal Manometry (HRM) uses a high-resolution catheter to measure intraluminal esophageal pressure. This method shows high sensitivity for HH diagnosis and helps to evaluate esophageal motility [12]. HRM plays a particularly crucial role prior to surgery in planning types of surgical treatment. HRM can be used to rule out motility disorders such as achalasia, which can mimic reflux. Unfortunately, this method is not generally available in clinical practice as HRM equipment is less accessible.

PH-metry is based on sensors placed in the esophagus. These sensors detect pH changes during a 24-hour period. This helps to detect and calculate acid refluxes in a 24-hour period, as well as to understand the connection between clinical symptoms and refluxes. PH-metry, before surgery, helps to differentiate “real” GERD from other similar conditions and avoid unnecessary operations. Recently a new method of Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance pH-metry (MII-pH) has been developed. Reflux monitoring using MII-pH technology is a relatively new technique and is currently considered the “gold standard” for GERD diagnosis. The movement of intraesophageal fluids is detected by MII-pH by measuring differences in electrical conductivity. Thus MII-pH can detect both acid and non-acid refluxes [13]. As GERD is frequently combined with HH type I, this method is used for the standard diagnostic workup in HH type I. In HH type II, III, IV, reflux symptoms are less common. Consequently, the significance of MII-pH in PEH is reduced, as negative results do not change the management procedure.

5. Medical management

Treatment of GERD with sliding HH (type I) is mostly conservative and based on diet, lifestyle changes and medical therapy. The objective of this chapter is not to review principles of medical treatment. Readers are referred to other sources regarding this topic. Our goal is to review the principles of surgical therapy in HH.

6. Surgical management

6.1 Indications for surgery

6.1.1 Sliding hiatal hernia (type I)

Asymptomatic sliding HH does not require specific therapy or surgical repair [14].

Surgical therapy for HH type I should be considered for:

Patients who have objective diagnosis of GERD (based on preoperative evaluation) and have inadequate symptom control by medical therapy.

Extra-esophageal GERD complications (confirmed on preoperative evaluation and exuded other reasons).

Patients with GERD and severe peptic complications like recurrent esophageal ulcer, peptic stricture, Barrett’s esophagus.

Patients with adequate control of GERD symptoms, but request surgery to avoid long-term prescription and side effects of medications.

6.1.2 Paraesophageal hiatal hernias (type II, III, IV)

Asymptomatic PEH, even large, is not an absolute indication for surgery [14]. The patient’s age and comorbidities should be taken into consideration.

For such patients, the strategy called “watchful waiting” is reasonable, because the annual risk of strangulation is less than 2% [15]. However, elective procedures encounter much less mortality compared with emergency procedures which have an average mortality rate about 17% [15].

For symptomatic PEH, surgical therapy should be considered in all cases. Age should not be a barrier to repair symptomatic PEH [14].

6.2 Surgical approaches

There are three main surgical approaches for HH repair: laparoscopic (currently the best), open transabdominal, open transthoracic.

6.2.1 Laparoscopic approach

Laparoscopic HH repair has good postoperative results with low mortality and morbidity rate. Additional preferences of laparoscopy include shorter hospital stays, less postoperative pain and better cosmetic results. Nowadays laparoscopy is the preferred approach for most hiatal hernia repairs [14].

6.2.2 Open transabdominal approach

The open transabdominal approach has similar results with laparoscopy but has a higher morbidity rate and longer hospitalization. Based on this, an open approach is reserved for patients when laparoscopy is not possible or is technically challenging. Indications for open abdominal surgery include patients who have had multiple upper abdominal surgeries in the past, patients who cannot tolerate laparoscopy and for technical considerations (e.g., complicated PEH, emergency situations, lack of experience).

6.2.3 Open transthoracic approach

Open transthoracic approach involves the longest hospital stays, the greatest need for mechanical ventilation postoperatively and the greatest risk of pulmonary embolism [16]. The advantages of the transthoracic approach are better visualization and greater ease of performing esophageal mobilization and the procedure for esophageal-lengthening. Given that, the open transthoracic approach is reserved for patients with large PEH (type IV) who are not candidates for transabdominal repair. However, in experienced hands, the laparoscopic transabdominal approach has been successful also with patients having giant PEH (type IV).

6.3 Surgical techniques

Considering recommendations, the majority of HH should be treated laparoscopically. This chapter will address laparoscopic techniques. The principles of open surgery are similar.

6.3.1 Patient position and port placement

The patient is placed in a modified low lithotomy position. Attention should be taken to correct thigh position relative to patient body—thigh should be at the same level as anterior abdominal wall, not elevated above (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The Patient’s position for laparoscopic HH repair. The thigh is not elevated above the abdominal wall.

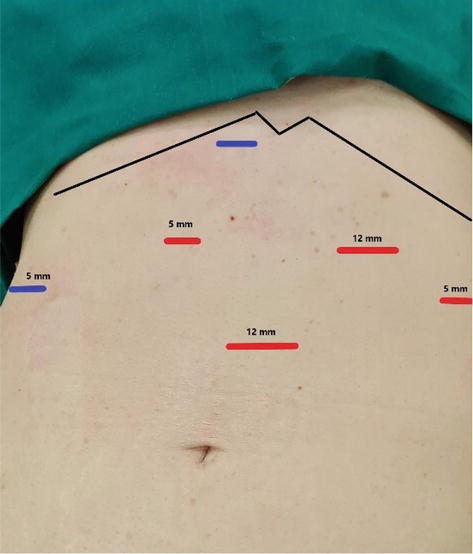

The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs. The reversed Trendelenburg position is used to facilitate exposure of the diaphragm and to displace the stomach inferiorly. Five ports are used in standard situations: the camera port is placed 1–2 cm to the left of the midline and 8–10 cm below the sternum. The second port is placed at the midclavicular line 2–3 cm below the left costal margin. Two additional 5 mm ports are placed. The fifth port could be placed in two different positions depending on the liver retractor. For a Fan Liver Retractor, port position is at the linea axillars anterior below right costal margin. For a Nathanson Liver Retractor, a small subxiphoid incision is performed (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Port placement (5 ports). Two ports (blue) could be placed in two different positions—Depends on liver retractor.

There are four critical steps in laparoscopic HH repair [17] (Video 1):

Excision of the hernia sac.

Sufficient mobilization of the intrathoracic esophagus to restore it intra-abdominal length.

Repair of the diaphragmatic crura.

Fundoplication.

6.3.2 Excision of the hernia sac

Dissection is started from the left or right diaphragmatic crus by dividing the phrenogastric membrane. The dissection is continued superiorly into mediastinum and the hernia sac is divided from mediastinal tissue. Short gastric vessels are divided to facilitate right crus dissection. A retroesophageal window is created and a drain is placed around the esophagus. This helps to retract the esophagus inferiorly and facilitate mediastinal dissection. After dissection, excision of the hernia sac is performed.

6.3.3 Sufficient mobilization of the intrathoracic esophagus to restore its intra-abdominal length

Aggressive mediastinal dissection is crucial to achieve sufficient length of the intra-abdominal esophagus (at least 3 cm). During dissection, care should be taken to avoid damage to the vagal nerves. Incomplete mobilization of the esophagus can lead to constant tension in the hiatal region and recurrence of the problem. In most cases, sufficient length could be achieved by deep intrathoracic mobilization of the esophagus. The esophagus must be mobilized to the level of the inferior pulmonary veins. In rare cases, the achievement of sufficient length is not possible (short esophagus). In such situations Collis gastroplasty could be the optimal choice. This maneuver elongates the esophageal length by the creation of a tube from the cardia part of the stomach. Usually, proximal resection of the stomach is performed with staplers. The 52-French bougie is inserted in the esophagus before resection to attain an optimal neo-esophagus diameter.

6.3.4 Repair of the diaphragmatic crura

The crura are sutured together using non-absorbable sutures. It could be an interrupted suture or a continuous suture. The use of the continuous suture technique fits with principles of abdominal wall closure—the continuous small-bite technique [18]. The use of barbed continuous sutures helps to facilitate closure in large defects. Closure starts inferiorly where right and left crura join together and proceed superiorly up to the esophagus. The 52-French bougie is placed in the esophagus and should pass easily after repair. Crus closure should not be very tight, so that the closed laparoscopic instrument could freely pass between the esophagus and the crura.

6.3.5 Prosthetic mesh for crura repair

A controversy exists about the use of mesh for crura repair. From one point of view, the only suture repair of PEH has a high radiology recurrence rate—up to 59% [19]. On the other hand, mesh implantation could lead to serious complications like mesh erosion and esophageal stenosis [20]. Different types of meshes exist on the market: synthetic non-absorbable, synthetic absorbable and biologic meshes.

Synthetic non-absorbable meshes are the most popular and differ in materials, knotting structure and weight. A common feature of such meshes is that they remain as a foreign body around the esophagus, constantly causing massive fibrosis, which decreases the possibility of recurrence. However, extensive fibrosis can lead to esophageal stenosis. Mesh migration could cause mesh erosion in the esophagus, mesh infection, sepsis and mediastinitis. Mesh related complications have been reported to range from 1.3 to 20% [21]. To redo surgery in the presence of non-absorbable mesh is a very challenging procedure, even in experienced hands due to dense adhesions and fibrosis.

Biological meshes cause less extensive fibrosis, and fewer complications. No erosions in the esophagus have been reported after biological mesh implantation. This is because of complete mesh resorption after some time. In one study, a long-term follow-up of 59 months showed no biological mesh related complications [22]. Unfortunately, the biggest disadvantage of biological meshes is the high rate of radiological recurrence—up to 54%, similar to that for sutured repairs [22]. This makes implantation of biological meshes questionable.

Synthetic absorbable meshes have short-term absorption (e.g., Vicryl ™) or long-term absorption (e.g., Phasix ™). Recently, slow absorbing synthetic meshes have appeared on the market (e.g., Phasix ™). Resorption times for these meshes are long—about 12–18 months. During this period the meshes cause dense fibrotic tissue to form, which should hold the diaphragmatic crura in desirable positions. On the other hand, the meshes will completely disappear with no foreign body formation. This means that esophageal mesh erosion or infection is not possible. In recent studies [23], these meshes show promising results in large PEH repair operations.

6.3.6 Fundoplication

Fundoplication is the procedure of creating a wrap with gastric fundus around the esophagus to make a one-way valve, that allows food passage to the stomach but does not allow reflux coming up to the esophagus. Fundoplication is an important part of the operation that improves the quality of life after surgery and decreases GERD symptoms.

There are three main methods of fundoplication: posterior 360°—Nissen, posterior 270°—Toupet and anterior 180°—Dor.

Posterior 360° fundoplication (Nissen fundoplication) is the most widely used type. To achieve a complete fundoplication and wrap the fundus around the esophagus, the division of the short gastric arteries is performed. A mobilized part of the fundus is drawn posterior to the esophagus toward the right, so that it completely wraps around the esophagus and meets the left part of the fundus anteriorly. Both parts of the fundus are stitched together and also attached to the anterior wall of the esophagus with 3 permanent stitches. The length of complete fundoplication is about 2–3 cm. The 52-French bougie is placed in the esophagus during fundoplication, so that the wrap should not be too tight.

Toupet fundoplication (posterior 270°) is a partial posterior fundoplication. The initial steps of this procedure are similar to Nissen fundoplication, with the difference being that fundus fixation is performed using stitches to the right and left walls of the esophagus, leaving the anterior wall free and creating a 270° wrap. For this method, usually 6 stitches are necessary (3 on each side).

Dor fundoplication (anterior 180°) is a partial anterior fundoplication. The initial steps are similar to posterior fundoplication, but mobilized fundus is wrapped anteriorly from the esophagus and fixed with stitches to the left and right walls of the esophagus. Anterior fundoplication is less physiological than posterior, because the Hiss angle is not created.

Both posterior fundoplications (Nissen and Toupet) have better long-term GERD symptom control than anterior fundoplication (Dor) [24, 25]. Dysphagia is the most common postoperative complication after fundoplication. Usually, it is transient and resolves after 3 months. In some studies, the incidence of dysphagia after Nissen fundoplication is as high as 70% [26]. Toupet fundoplication has less postoperative dysphagia when compared to Nissen fundoplication [27]. Another common complaint after fundoplication is inability to belch or vomit, including excess flatulence and abdominal bloating. These complaints were found in up to 60% of the patients and did not depend on type of fundoplication [28].

7. Adverse outcome and failure after hiatal hernia surgery

In most cases, failure of the fundoplication depends on 3 factors: wrong indications and preoperative workup, technical issues, or wrong postoperative workup.

7.1 Wrong indication and preoperative workup

In many cases, indication for HH type I surgery is relative. Based on this, preoperative workup plays an important role in patient selection for surgery. All complications and side effects should be taken into consideration before surgery. Objective studies of GERD—pH monitoring, manometry, upper GI endoscopy and barium swallow—are important to evaluate preoperative condition and make decisions for or against surgery. Sometimes, CT provides additional information about surrounding organs and helps to make correct diagnosis. Anamnesis and previous history of medical therapy are also important.

Obesity is an important factor influencing the result of HH surgery. It has been shown that obese patients have a higher risk of HH recurrence. In such cases, a decision could be made in favor of Roux-en-Y bypass with hiatoplasty as a primary operation. This surgery could solve both problems—decrease GERD symptoms due to low acidity in redundant stomach and decrease the patient’s weight.

Tobacco usage is a well-known risk factor for hernia surgery failure. It causes wound and connective tissue healing problems, as well as chronic cough which leads to constant mechanical irritation of the repaired area. Therefore, nicotine addiction should be eliminated or reduced preoperatively.

PEH surgery is more complicated, takes a longer time and has more side effects. Moreover, many patients with large PEH are elderly and have multiple comorbidities. It is good to remember that asymptomatic PEH is not an absolute indication for surgery because severe complications like volvulus are rare [14]. In some complicated or acute cases, hernia reduction with gastropexy alone (without HH repair) could be a safe alternative for high-risk patients [29].

7.2 Technical issues

Hernia sac dissection is essential to release the tethering of the esophagus and achieve sufficient length of the abdominal esophagus. It is recommended to perform sac excision. However, in large hernias, it can be difficult. It can predispose vagal injury and lead to gastroparesis. For this reason, some authors advocate sac dissection without excision or with only partial sac excision [30].

Crural reinforcement with mesh in large PEH decreases short-term recurrence. Unfortunately, there is lack of long-term data for or against the use of mesh and about type of mesh [14].

Fundoplication plays an essential role in HH surgery and should be done routinely in all cases, except for morbid patients with gastropexy only [14]. Currently, posterior fundoplication has better outcomes when compared to anterior fundoplication in terms of symptom control. Posterior fundoplication is recommended in most cases.

7.3 Postoperative workup

Early postoperative vomiting, belching, or gagging suddenly increase intra-abdominal pressure and are predisposing factors for recurrence. Aggressive treatment and prophylactic medications (e.g., ondansetron) in the early postoperative period are recommended for these factors [14].

Gastric distension and gastroparesis can lead to dangerous complications in the early postoperative period, especially after large PEH surgery. Placement of the nasogastric tube usually helps in most cases. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy can be indicated sometimes. Gastric distension usually decreases spontaneously after a short time. In refractory cases, gastrojejunostomy or pyloroplasty could be the solution [31]

Early postoperative dysphagia is a common complication after HH surgery. Attention should be paid to slow diet advancement from liquids to solids. If dysphagia persists longer than 3 months and weight loss of more than 10 kg occurs, an intervention for the dysphagia should be performed.

8. Recurrent hiatal hernia

Recurrence rates after HH surgery vary. We can distinguish symptomatic recurrence and radiologic recurrence. Radiologic recurrence is confirmed by a barium esophagogram. It shows HH larger than 2 cm above the diaphragm. Some sources declare that radiologic recurrence after PEH repair is up to 59% [19]. In most cases, radiologic recurrence is asymptomatic or mild and does not require revisional surgery. However, in 5% of cases, symptoms are significant and intervention is needed [32]. In most cases, symptoms are dysphagia, regurgitation, nausea, burning, early satiety, chest pain or postprandial dyspnea. In some cases, mechanical pressure can lead to Cameron’s ulcer of the mucosa and bleeding.

Gastric motility should be taken into consideration before surgery. Poor gastric emptying and hypomotility could lead to gastrostasis, bloating, nausea and severe reflux. In these cases, gastric series with barium helps the diagnosis of the problem. Endoscopy with Botulinum toxin injection in the pylorus may decrease symptoms for 3–6 months. The definitive therapy for this problem is pyloroplasty or another gastric drainage procedure (pyloric dilatation, peroral pyloromyotomy etc.) [33].

When surgical intervention is decided, thorough planning should be done. Revisional HH surgery is challenging. The surgical approach could be transabdominal or transthoracic. It depends on the surgeon’s experience and preference. Laparoscopy could be safely performed in most cases, however, dissection should be done with caution. Postoperative adhesions can lead to organ damage and are found in up to 30% of cases [34]. Failure of pervious fundoplication is a common reason for recurrence. Thus

Obese patients with BMI > 35 kg/m2 should be advised for revision using the bariatric procedure. It is known that obesity is an independent risk factor for HH recurrence. On the other side, Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) decreases weight and gives good control over GERD symptoms [35]. Thus, revisional surgery combination with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass could be a preferred option for prevention of future recurrences. In addition, it is known that HH reconstruction in combination with LRYGB does not lead to increased morbidity and mortality in comparison with LRYGB alone [36].

9. Novel techniques in hiatal hernia surgery

Linx ™, a new mechanical device for GERD treatment was recently presented and approved [37]. The Linx ™ is constructed from biocompatible titanium beads with magnetic cores hermetically sealed inside. The bead can move independently and the diameter of this device changes during esophageal movements. So, patients can swallow and eat without any resistance but for reflux to occur, the intragastric pressure should overcome the magnetic sphincter pressure. This is an alternative for the fundoplication procedure and could be used in small hiatal hernia surgery, as the only solution or as additional step after crural closure. This procedure is less invasive and less complicated than fundoplication. A study of the first 1000 implants worldwide showed 5.6% of cases needed endoscopic dilatation and 3.4% required reoperation. The main reason for removal of the devices was dysphagia and the recurrence of reflux [38]

10. Conclusion

HH is a widespread problem in western populations. Treatment is multidisciplinary and requires the involvement of many specialists. While management of HH type I is mostly conservative and based on diet, lifestyle changes and medical therapy, symptomatic PEH (HH type II, III, IV) treatment is surgical. Recent advances in minimally invasive surgery (i.e., laparoscopic surgery) have significantly improved the results of surgical procedures, however, many controversies still exist in HH management (e.g., sutured repair or mesh placement). The development of new materials and procedures, the standardization of guidelines and surgical methods will continue to improve treatment results and the quality of life for patients in the future.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Greg MacDonald PhD. from Riseba University of Applied Sciences, Riga for his help.

I also sincerely thank Olga Berdnikova for her support and assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.

Dunn CP, Patel TA, Bildzukewicz NA, Henning JR, Lipham JC. Which hiatal hernia’s need to be fixed? Large, small or none? Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. 2020; 5 :29. DOI: 10.21037/ales.2020.04.02 - 2.

Menon S, Trudgill N. Risk factors in the aetiology of hiatus hernia: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011; 23 (2):133-138. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283426f57 - 3.

Dellaportas D, Papaconstantinou I, Nastos C, Karamanolis G, Theodosopoulos T. Large Paraesophageal hiatus hernia: Is surgery mandatory? Chirurgia (Bucur). 2018; 113 (6):765-771. DOI: 10.21614/chirurgia.113.6.765 - 4.

Carrott PW, Hong J, Kuppusamy M, Koehler RP, Low DE. Clinical ramifications of giant paraesophageal hernias are underappreciated: Making the case for routine surgical repair. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2012; 94 (2):421-426; discussion 426-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.058 Epub 2012 Jun 27 - 5.

Pauwels A. Dental erosions and other extra-oesophageal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Evidence, treatment response and areas of uncertainty. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2015; 3 (2):166-170. DOI: 10.1177/2050640615575972 - 6.

Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006; 55 (10):1398-1402. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668 Epub 2006 Mar 23 - 7.

Lebenthal A, Waterford SD, Fisichella PM. Treatment and controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair. Frontiers in Surgery. 2015; 2 :13. DOI: 10.3389/fsurg.2015.00013 - 8.

Brar HS, Aloysius MM, Shah NJ. Cameron Lesions. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; - 9.

Weitzendorfer M, Köhler G, Antoniou SA, Pallwein-Prettner L, Manzenreiter L, Schredl P, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of hiatal hernia: Barium swallow X-ray, high-resolution manometry, or endoscopy? European Surgery. 2017; 49 (5):210-217. DOI: 10.1007/s10353-017-0492-y Epub 2017 Sep 19 - 10.

Weijenborg PW, Van Hoeij FB, Smout AJPM, Bredenoord AJ. Accuracy of hiatal hernia detection with esophageal high resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2015; 27 :293-299 - 11.

Laracca GG, Spota A, Perretta S. Optimal workup for a hiatal hernia. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. 2021; 6 :2. DOI: 10.21037/ales.2020.03.02 - 12.

Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE, International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2015; 27 :160-174 - 13.

Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: The Lyon consensus. Gut. 2018; 67 (7):1351-1362. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722 - 14.

Kohn GP, Price RR, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Muensterer OJ, Awad Z, et al. Fanelli RD; SAGES guidelines committee. Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernia. Surgical Endoscopy. 2013; 27 (12):4409-4428. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-013-3173-3 Epub 2013 Sep 10 - 15.

Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal hernias: Operation or observation? Annals of Surgery. 2002; 236 (4):492-500; discussion 500-1. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00012 - 16.

Paul S, Nasar A, Port JL, Lee PC, Stiles BC, Nguyen AB, Altorki NK, Sedrakyan A. Comparative analysis of diaphragmatic hernia repair outcomes using the nationwide inpatient sample database. Arch Surg. 2012;147(7):607-612. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.127. Erratum in: Archives of Surgery 2012;147(9):804 - 17.

DeMeester SR. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: Critical steps and adjunct techniques to minimize recurrence. Surgical Laparoscopy, Endoscopy & Percutaneous Techniques. 2013; 23 (5):429-435. DOI: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182a12716 - 18.

Deerenberg EB, Henriksen NA, Antoniou GA, Antoniou SA, Bramer WM, Fischer JP, et al. Updated guideline for closure of abdominal wall incisions from the European and American Hernia Societies. British Journal of Surgery. 2022; 109 (12):1239-1250. DOI: 10.1093/bjs/znac302 Erratum in: Br J Surg. 2022 Nov 10 - 19.

Kao AM, Otero J, Schlosser KA, Marx JE, Prasad T, Colavita PD, et al. One more time: Redo Paraesophageal hernia repair results in safe, durable outcomes compared with primary repairs. The American Surgeon. 2018; 84 (7):1138-1145 - 20.

Gordon AC, Gillespie C, Son J, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic large hiatus hernia repair with nonabsorbable mesh. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2018; 31 (5):156 - 21.

Memon MA, editor. Hiatal Hernia Surgery: An Evidence Based Approach. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2017. pp. 134-147. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-64003-7 - 22.

Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG, Brunt ML, Soper NJ, Sheppard BC, et al. Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: Long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; 213 (4):461-468. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.017. Epub 2011 Jun 29. Erratum in: Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2011;213(6):815 - 23.

Jushko M, Ivanovs I. Quality of life after hiatal hernia repair with biosynthetic mesh Phasix. Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences, Section B: Natural, Exact and Applied Sciences. 2022; 76 :632-635. DOI: 10.2478/prolas-2022-0097 - 24.

Engström C, Lönroth H, Mardani J, Lundell L. An anterior or posterior approach to partial fundoplication? Long-term results of a randomized trial. World Journal of Surgery. 2007; 31 (6):1221-1225; discussion 1226-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-007-9004-8. Epub 2007 Apr 24 - 25.

Nijjar RS, Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Archer S, Bessell JR, Booth M, et al. International Society for the Diseases of the esophagus-Australasian section. Five-year follow-up of a multicenter, double-blind randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen vs anterior 90 degrees partial fundoplication. Archives of Surgery. 2010; 145 (6):552-557. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.81 - 26.

Sato K, Awad ZT, Filipi CJ, Selima MA, Cummings JE, Fenton SJ, et al. Causes of long-term dysphagia after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. JSLS. 2002; 6 (1):35-40 - 27.

Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Antoniou SA, Luketina RR, Emmanuel K, Pointner R. Comparison of results from a randomized trial 1 year after laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplications. Surgical Endoscopy. 2013; 27 (7):2383-2390. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-013-2803-0 Epub 2013 Jan 30 - 28.

Courtney O, Peter N. Anterior Versus Posterior Fundoplication, Are They Equal? In: Muhammed AM, editor. Hiatal Hernia Surgery: An Evidence Based Approach. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2017. pp. 91-102. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-64003-7 - 29.

Rosenberg J, Jacobsen B, Fischer A. Fast-track giant paraoesophageal hernia repair using a simplified laparoscopic technique. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2006; 391 :38-42 - 30.

Trus TL, Bax T, Richardson WS, Branum GD, Mauren SJ, Swanstrom LL, et al. Complications of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 1997; 1 (3):221-227; discussion 228. DOI: 10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80113-8 - 31.

Li Z, Xie F, Zhu L, et al. Post-operative gastric outlet obstruction of giant hiatal hernia repair: a case report. BMC Gastroenterology. 2022; 22 :47. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-022-02117-z - 32.

Elhefny, Amr M.M.a; Elmaleh, Haitham M.a; Hamed, Mohammed A.a; Salem, Hossam E.-D.M.b. Laparoscopic management of recurrent symptomatic hiatal hernia with and without mesh repair: a comparative prospective study. The Egyptian Journal of Surgery 40(4): p. 1064-1073, October-December 2021. DOI: 10.4103/ejs.ejs_90_21 - 33.

Botha AJ, Di Maggio F. Management of complications after paraesophageal hernia repair. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. 2021; 6 :38. DOI: 10.21037/ales-19-241 - 34.

Juhasz A, Sundaram A, Hoshino M, Lee TH, Mittal SK. Outcomes of surgical management of symptomatic large recurrent hiatus hernia. Surgical Endoscopy. 2012; 26 (6):1501-1508. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-011-2072-8 Epub 2011 Dec 17 - 35.

Khan M, Mukherjee AJ. Hiatal hernia and morbid obesity-'Roux-en-Y gastric bypass' the one step solution. Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2019; 2019 (6):rjz189. DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rjz189 - 36.

Kothari V, Shaligram A, Reynoso J, Schmidt E, McBride CL, Oleynikov D. Impact on perioperative outcomes of concomitant hiatal hernia repair with laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery. 2012; 22 (10):1607-1610. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-012-0714-0 - 37.

Ganz RA, Peters JH, Horgan S, Bemelman WA, Dunst CM, Edmundowicz SA, et al. Esophageal sphincter device for gastroesophageal reflux disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013; 368 (8):719-727. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205544 - 38.

Lipham JC, Taiganides PA, Louie BE, Ganz RA, DeMeester TR. Safety analysis of first 1000 patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2015; 28 (4):305-311. DOI: 10.1111/dote.12199 Epub 2014 Mar 11 - 39.

Asti E, Siboni S, Lazzari V, Bonitta G, Sironi A, Bonavina L. Removal of the magnetic sphincter augmentation device: Surgical technique and results of a single-center cohort study. Annals of Surgery. 2017; 265 (5):941-945. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001785