Benign and malignant tumors of lingual and palatine tonsil [1].

Abstract

Tonsils are lymphoid tissues in the oral cavity and nasopharyngeal region arranged in Waldeyer’s ring. The Waldeyer’s ring consists of pairs of pharyngeal (adenoids), tubal, palatine, and lingual tonsils. These are usually hyperplastic at a younger age and decrease with age. However, asymmetric enlargement might be a sign of pathology. It could be due to tonsillitis, abscess, and benign tumors, such as fibromas, teratomas, and angiomas such as lymphangioma, hemangioma, and inclusion cyst. Benign tumors of the tonsils are usually rare but not uncommon. It could be due to malignancies such as lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or metastasis. This chapter focuses on clinical, histopathological and radiographic features of benign and malignant tumors of palatine and lingual tonsils.

Keywords

- lingual tonsil

- palatine tonsil

- tonsillar carcinoma

- tonsillar tumor

- classification of tonsillar tumors

1. Introduction

Tonsils are developed from the second branchial cleft. This location corresponds to the intersection of oral epiblast and intestinal hypoblast. According to embryology, an organ formed from combining two different tissues has more potential for neoplastic growth [2]. Although benign and malignant tumors of the tonsillar region are more common, there is very scarce literature regarding the definitive classification of tonsillar tumors. In the WHO classification of tumors of the oropharynx, tonsillar tumors are included along with the base of the tongue and adenoids. This chapter focuses exclusively on palatine and lingual tonsillar tumors. These tumors are comprehensively classified according to the histologic nature of the lesion (Table 1).

| Benign tumors | Malignant tumors |

|---|---|

| Fibroma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Lymphangioma/lymphoid polyp | Lymphoma—Hodgkin’s and Non-Hodgkin’s |

| Squamous cell papilloma | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| Lipoma | Adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| Fibroxanthoma (histiocytoma) | Melanoma |

| Chondromas | Sarcomas: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma Synovial sarcoma Angiosarcoma Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Mixed tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) | Metastatic malignancies |

| Oncocytoma, ganglioneuroma, neurilemmoma pigmented nevus, hamartoma | Plasmacytoma (extramedullary) |

Table 1.

2. Benign tumors of tonsils

Benign tumors of the tonsils are rarer than malignant tumors. Most benign tumors of the tonsils are reported in the younger age group. Most patients are asymptomatic, and a benign tumor is often detected as an incidental finding. Other clinical symptoms include the presence/sense of mass, sore throat, and difficulty swallowing/breathing. Most benign tumors of the tonsil manifest in the form of a polyp, and clinical signs and symptoms are identical. The histopathological examination provides a definitive diagnosis of the lesion based on the tissue of origin. Table 1 provides a list of benign tumors. The clinical features of common benign tonsillar tumors are discussed below.

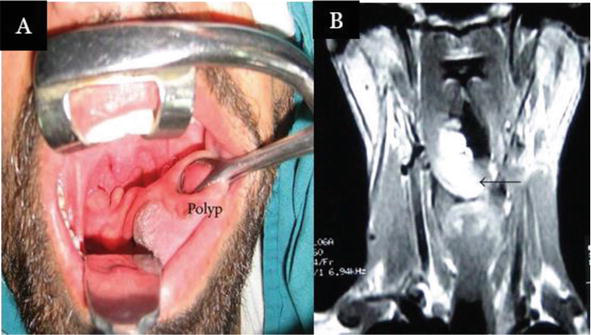

2.1 Hamartomatous fibrous polyps/fibro-epithelial polyp/tonsillar fibroma

These present as a polypoid mass attached to the tonsil. It may be sessile/pedunculated (Figure 1). The patient recognizes mass after it attains a specific size and interferes with functional movements such as deglutition. The most common clinical features include pale pink color, lymphadenopathy, and asymptomatic lesion. However, patients might present with cough or foreign body sensation. Reports of airway obstruction due to benign tonsillar mass are scarce. The rate of malignant transformation is significantly less.

Figure 1.

Well-defined, smooth-surfaced fibroepithelial polyp (yellow arrows) arising from the superior pole of the right palatine tonsil [

2.2 Lymphoid tonsillar mass/Lymphangiomatous polyp

Lymphangiomatous polyps are congenital tumors of the lymphatic system. They are hamartomatous malformations. They are present at birth or manifest in early life (Figure 2). The clinical presentation would be similar to a fibroma. Bilateral occurrence is rare, although few cases are reported in the literature [5].

Figure 2.

Pedunculated polyp of lymphoid origin in the right palatine tonsil [

2.3 Papilloma

It is one of the common benign neoplasms of the tonsil. Clinically they present as grayish-white exophytic lesions with a wrinkled surface. The lesions may be either sessile/pedunculated.

2.4 Lipoma

Lipomas are mesenchymal tumors of fat cells. They are seen less frequently in the head and neck region, especially the tonsillar area. They are benign, slow-growing tumors. The clinical presentation would be similar to other benign tumors. Lipomas can be lobulated. Extensive lipoma might cause airway obstruction.

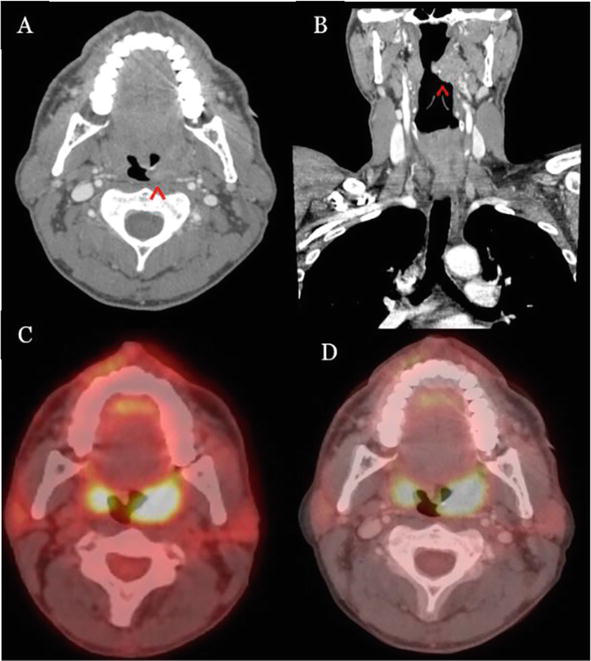

Figure 3.

Axial section of contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating a pedunculated lipoma arising from right palatine tonsil. Notice the non-enhancement of the lesion [

Figure 4.

Clinical presentation of tonsillar lipoma (A) and coronal section of T2-weighted MRI image demonstrating hyperintense lesion (B) [

2.5 Management of Benign tumors of tonsils

Most benign tumors, such as lipoma, fibroma, papilloma, and lymphangioma, present as polypoid masses. Tonsillectomy and surgical excision of the lesion, followed by histopathologic examination, is the most common treatment option. The definitive diagnosis is based on the predominant tissue in the excised specimen. Few cases can be managed with the excision of polypoid mass without tonsillectomy, especially if the polypoid mass is pedunculated [7]. There is less chance for recurrence and malignant transformation of benign tumors of the tonsils. The prognosis is usually good for benign tumors.

3. Malignant tumors of tonsils

Oropharyngeal (OP) cancers include tumors arising from the palatine tonsil, the base of the tongue, the walls of the pharynx, and the soft palate. Palatine tonsils constitute lymphoid tissue embedded in the tonsillar fossa located in the lateral walls of the oropharynx between the tonsillar pillars. Palatine tonsils cancers comprise tumors of the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillar, tonsillar fossa, and plica triangularis. The lingual tonsil constitutes lymphoid tissue in the base of the tongue. Lingual tonsillar cancers comprise tumors of the base of the tongue.

Tonsilar squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) are the most common malignant tonsillar neoplasms, followed by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Most oropharyngeal SCCs (OPSCC) are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV). Tobacco, smoking habits, iron deficiency, avitaminosis, and syphilis have been implicated as other etiology factors for tonsillar neoplasms. The overall incidence of Head and neck SCC (HNSCC) has been reducing since the 1980s due to declining smoking. However, there is a rapid increase in human papillomavirus (HPV) induced OPSCC in younger patients [8].

The presenting symptoms for most tonsillar neoplasms are sore throat, local pain, and the sensation of a mass in the neck. The tonsillar growth begins as a superficial granular ulcer in the tonsillar region. Eventually, the ulcer erodes the surface. They produce a submucosal mass with or without surface ulceration. Tonsillar tumors might spread to alveolar ridges and buccal mucosa. Tonsillar neoplasms metastasize to uni/bilateral lymph nodes and present as lymphadenopathy. Radiating pain in the ear is characteristic of advanced tonsillar malignancy. During initial medical diagnosis, most malignant tonsillar tumors are in advanced stages or extended beyond the tonsil. The poor tactile sensation in the tonsillar region compared to the oral cavity could be the reason for the occult nature of tonsillar malignancies [9].

Both carcinomas and lymphomas present as asymmetric enlargements of the tonsil. It is challenging to differentiate from clinical examination. Some lymphomas present as bilateral tonsillar masses. There is conflicting literature regarding the excision of unilateral asymmetric enlarged tonsils without other suspicious features of malignancy. However, a tumor should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of these cases, and judicious follow-up is recommended [10].

3.1 Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Due to the inherent lack of afferent lymphatic channels, carcinoma in the tonsils is likely a primary malignancy rather than metastasis [11].

The palatopharyngeus muscle forms the posterior tonsillar pillar. Tumors in this region can spread to the soft palate, thyroid cartilage, pterygomandibular raphe, and oral cavity. The posterior tonsillar pillar drains only into level II nodes. But if a tumor spreads to the oropharynx, this region drains into level V and retropharyngeal nodes [12].

Figure 5.

Bilateral tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma [

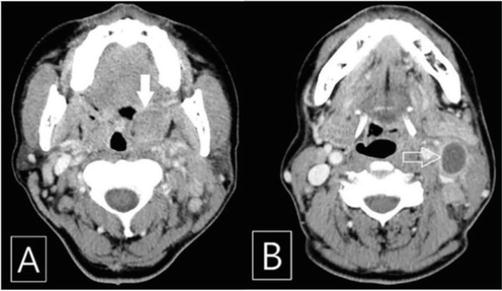

3.2 Lymphoma

Lymphoma accounts for the second most common malignancies of the head and neck. Most head and neck lymphomas are Hodgkin, and only 5% are non-Hodgkin. The tonsils are the most common site of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the head and neck region. The clinical symptoms of primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the tonsils include a sore throat or feeling of a lump in the throat, lymphadenopathy, dysphagia, and occasionally systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats. It usually has a rapid onset with a short clinical course of a few weeks and predominantly occurs in the older age group.

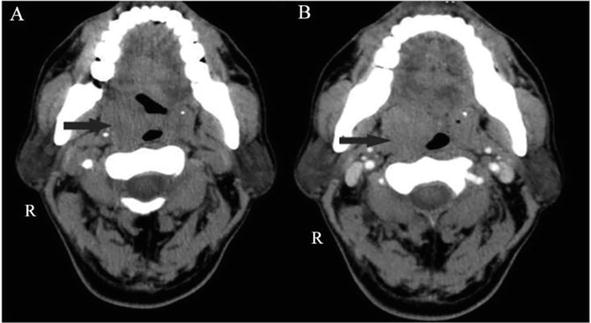

Figure 6.

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) scan of the patient. (A) Hypertrophic and slightly enhanced left palatine tonsil (solid arrow) and (B) enlarged ipsilateral cervical lymph node demonstrating central low attenuated lesion (arrow) [

3.3 Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC)

It is the most common primary salivary gland malignancy. It can occur in the minor salivary glands of the palatine tonsils. Patients might present with asymptomatic swelling that eventually progresses to an ulcerated mass. Few tumors present as fluctuant masses with a blue or red hue identical to mucocele.

Figure 7.

Axial CT image demonstrating solid lesion of MEC with lobulated and ill-defined margins [

3.4 Adenocarcinomas

Most of the adenocarcinomas in the palatine tonsils are metastatic from the lung and gastrointestinal tract. In recent times, the number of tonsillar carcinomas associated with HPV 16 has increased, and most of them were SCC. There are few case reports of HPV p16-positive adenocarcinomas. HPV-associated adenocarcinomas occur in younger patients. They comprise less than 1% of all malignancies of palatine tonsils.

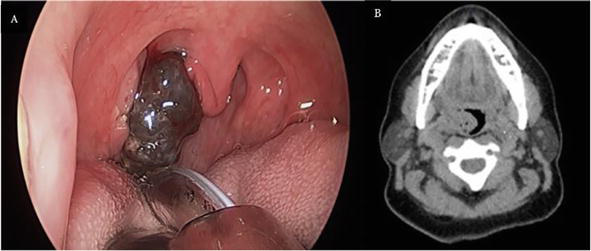

3.5 Melanoma

Primary mucosal melanoma accounts for 1.3% of cases in the head and neck region. In descending order, the primary sites in the head and neck region include the nose and paranasal sinuses, oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. The oropharynx is not a common site of mucosal melanoma. Mucosal melanoma is more common in males than females; the average age is 61–65. Melanoma usually has a poor prognosis, so an early diagnosis has a better outcome.

Figure 8.

(A) Clinical image demonstrating extensive, pigmented exophytic lesion (metastasis to palatine tonsil from a cutaneous melanoma); and (B) Non-contrast CT axial section demonstrating exophytic right tonsillar mass [

3.6 Sarcoma

Tonsillar sarcomas are not very common. Unlike tonsillar squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas grow rapidly and spread through visceral metastasis. The etiopathogenesis of sarcoma is unknown. Detailed knowledge of tonsillar anatomy is important to understand sarcoma’s signs and symptoms and decide on treatment. The superior boundary of the tonsils is formed by the junction of the soft palate and facial pillars and is inferiorly continuous as vallecula. Inferiorly, if lymphoid tissues are more, no line of distinction is present between facial and lingual tonsils. Tonsils are separated from the carotid sheath by the middle constrictor muscle of the pharynx. Tonsils are not directly attached to the anterior pillar or the plica triangularis. A fairly moderate size sarcoma at the superior aspect of the tonsils can cause displacement of the supratonsillar fossa. A larger mass at this site can cause displacement of the uvula and soft palate bulging. A large tumor mass at the inferior aspect can mimic an indurated fixed lymph node due to displacement of the tissues below the jaw angle. Tumor present between the superior and inferior extent (middle third) can be visualized by tongue depression.

Figure 9.

(A) CT scan demonstrating a well-circumscribed, homogeneously enlarged 4.6 × 2.5 × 2.5-cm right tonsil; and (B) post-contrast image demonstrating slight continuing heterogeneous enhancement [

3.7 Metastatic malignancies

Metastasis to palatine tonsils is extremely rare. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature. The mechanism of metastasis is unclear. It could occur through the retrograde lymphatic spread, hematogenous or paravertebral plexus from lungs, or through direct inoculation of lung tumor through bronchoscopy. Physical examination might reveal swollen and edematous tonsils. The patient may have difficulty in breathing, pain, and discomfort. Tonsillar metastasis is often detected as an incidental finding during the routine oral examination. In some cases, the patient might have symptoms such as a sore throat and the sensation of a mass in the neck. Tonsillar metastasis can be uni/bi-lateral depending on the primary neoplasm [27].

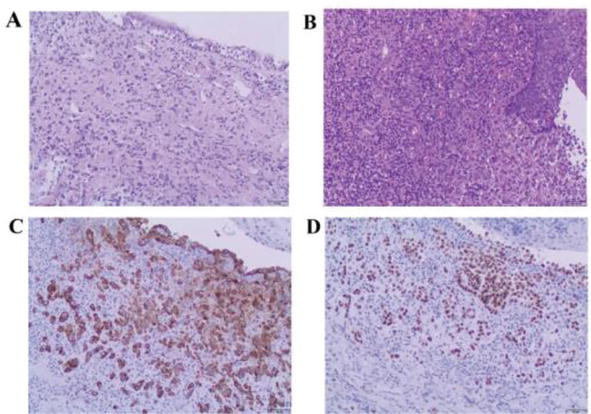

Figure 10.

(A) Respiratory columnar epithelium of the right medial main bronchus undermined by a poorly differentiated carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification, ×100); (B) Stratified squamous epithelium of the right palatine tonsil demonstrating histologically identical cancerous infiltrate (magnification, ×100); (C) Cytokeratin 7; and (D) thyroid transcription factor-1 positivity establish the diagnosis of metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma (magnification, ×100) [

3.8 Extramedullary Plasmacytoma (EMP)

Plasmacytomas are malignancies of plasma cells that primarily involve bone. Sometimes, plasmacytomas occur in soft tissues, called extramedullary plasmacytomas (EMP). These tumors are usually rare and occur mostly in the upper aerodigestive tract. EMPs are extremely rare in the tonsillar region. Clinical presentation includes painless mass, unilateral swelling in the tonsillar region, and lymphadenopathy. There are case reports of bilateral EMP. FNAC might be inconclusive in some cases due to difficulty in distinguishing from reactive lesions.

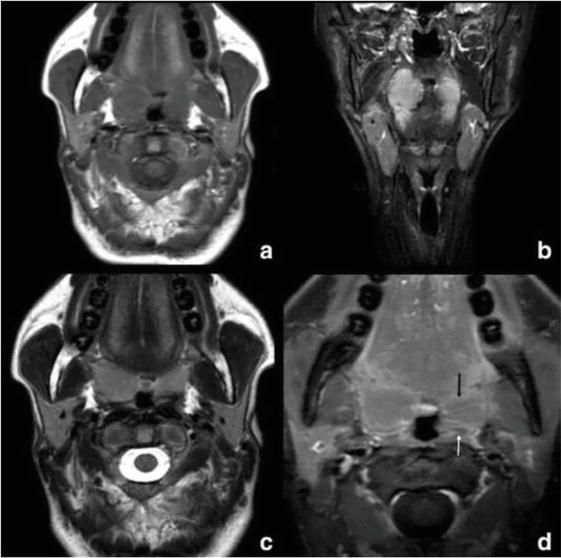

Figure 11.

Tonsillar plasmacytoma: (a) Axial non-contrast T1W; (b) coronal STIR; and (c) Axial T2W and d. postgadolinium T1W with fat saturation MR images. The arrow in image d demonstrates the obliteration of the right palatine tonsillar crypts combined with linear horizontal enhancement to the left [

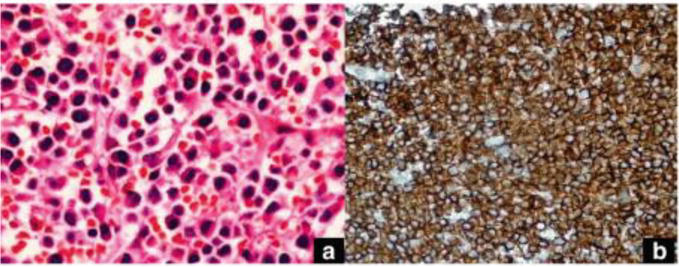

Figure 12.

(a) Plasma cells with an eccentric nucleus and abundant cytoplasm (hematoxylin–eosin × 40); and (b) Diffuse cytoplasmic, focal membranous CD138 staining on the plasma cells (streptavidin-biotin peroxidase × 400) [

4. Conclusion

Majority of benign tumors of the tonsils are managed with surgical excision of tumors with or without tonsillectomy. There is a low chance of recurrence and the prognosis is usually good for benign tumors. Early diagnosis and intervention determine the prognosis for malignant tonsillar tumors. The overall survival rate is better with HPV-positive tumors than with HPV-negative. The high survival rate in HPV-positive cases can be reduced by smoking. The other factors that help to improve prognosis include young age, localized tumor with lack of metastasis, and low comorbidities. CECT/MRI are recommended imaging modalities. The diagnosis of CECT sequences in the maxillofacial region is limited due to the streak artifact. The small primary mucosal tumors are difficult to diagnose; hence clinical evaluation is complimentary, and the thin CT sections help for better assessment. Underdiagnosing the primary lesion by failure to recognize invasion and lymph node metastasis can lead to poor prognosis. Careful evaluation of adjacent soft tissues and osseous structures, involvement of retropharyngeal lymph nodes on ipsilateral/contralateral sites, and detailed knowledge of anatomy are vital for better disease control and prognosis.

References

- 1.

Hyams VJ. Differential diagnosis of neoplasia of the palatine tonsil. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 1978; 3 :117-126 - 2.

Hara HJ. Benign tumors of the tonsil: with special reference to fibroma. Archives of Otolaryngology. 1933; 1 :62-69 - 3.

Marini K, Garefis K, Skliris JP, Peltekis G, Astreinidou A, Florou V. Fibroepithelial polyp of palatine tonsil: A case report. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2021; 39 :276 - 4.

Balatsouras DG, Fassolis A, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Kaberos A. Primary lymphangioma of the tonsil: A case report. Case Reports in Medicine. 2011; 2011 :31 - 5.

Gan W, Xiang Y, He X, Feng Y, Yang H, Liu H, et al. A CARE-compliant article: Lymphangiomatous polyps of the palatine tonsils in a miner: A case report. Medicine. 2019; 98 (1) - 6.

Unzué G, Viteri G, Alberdi N, López P, de Llano L, Lage T, et al. Lipoma of palatine tonsil. Section head and neck imaging. Eurorad. 2020. DOI: 10.35100/eurorad/case.17083 - 7.

Kanotra SP, Davies J. Management of tonsillar lipoma: Is tonsillectomy essential? Case Reports in Otolaryngology. 2014; 2014 :4 - 8.

Filion E, Le QT. Oropharynx: Epidemiology and treatment outcome. In: Functional Preservation and Quality of Life in Head and Neck Radiotherapy. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. pp. 15-29 - 9.

Martin H, Sugarbaker EL. Cancer of the tonsil. The American Journal of Surgery. 1941; 52 (1):158-196 - 10.

Cinar F. Significance of asymptomatic tonsil asymmetry. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004; 131 (1):101-103 - 11.

Heffner DK. Pathology of the tonsils and adenoids. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 1987; 20 (2):279-286 - 12.

Corey A. Pitfalls in the staging of cancer of the oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Neuroimaging Clinics. 2013; 23 (1):47-66 - 13.

Rossi NA, Reddy DN, Rawl JW, Dong J, Qiu S, Clement CG, et al. Synchronous tonsillar tumors with differing histopathology: A case report and review of the literature. Cancer Reports. 2022; 5 (9):e1615 - 14.

Weber AL, Romo L, Hashmi S. Malignant tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx: Clinical, pathologic, and radiologic evaluation. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 2003; 13 (3):443-464. DOI: 10.1016/s1052-5149(03)00037-6 - 15.

Rousseau A, Badoual C. Head and Neck: Squamous cell carcinoma: An overview. Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology. Mar 2012; 16 (2):145-155 - 16.

Kim YC, Kwon M, Kim JP, Park JJ. A case of malignant lymphoma misdiagnosed as acute tonsillitis with subsequent lymphadenitis. Kosin Medical Journal. 2019; 34 (1):78-82 - 17.

Wang XY, Wu N, Zhu Z, Zhao YF. Computed tomography features of enlarged tonsils as the first symptom of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2010; 29 (5):556-560 - 18.

King AD, Lei KI, Ahuja AT. MRI of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the palatine tonsil. The British Journal of Radiology. 2001; 74 (879):226-229 - 19.

Vardiman JW. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: An overview with emphasis on the myeloid neoplasms. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 19 Mar 2010; 184 (1-2):16-20 - 20.

Teixeira LN, Montalli VA, Teixeira LC, Passador-Santos F, Soares AB, Araújo VC. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the palatine tonsil. Case Reports in Oncological Medicine. 2015; 2015 :15 - 21.

Damato S, Thavaraj S, Winter S, Shah K. Human papillomavirus-associated adenocarcinoma of the palatine tonsil. Human Pathology. 2014; 45 (4):893-894 - 22.

Sethi A, Sundermann J, Neeta P. Human Papillomavirus induced adenocarcinoma of tonsil: A rare entity. Clinical Oncological Case Report. 2022; 5 :2 - 23.

Barton BM, Ramsey T, Magne JM, Worley NK. Delayed metastatic melanoma to the pharyngeal tonsil in an African American female. Ochsner Journal. 2019; 19 (2):181-183 - 24.

Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: A review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997; 80 (8):1373-1386 - 25.

Lu ZJ, Li J, Zhou SH, Dai LB, Yan SX, Wu TT, et al. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the right tonsil: A case report and literature review. Oncology Letters. 2015; 9 (2):575-582 - 26.

O’Neill JP, Bilsky MH, Kraus D. Head and neck sarcomas: Epidemiology, pathology, and management. Neurosurgery Clinics. 2013; 24 (1):67-78 - 27.

Bar R, Netzer A, Ostrovsky D, Daitzchman M, Golz A. Abrupt tonsillar hemorrhage from a metastatic hemangiosarcoma of the breast: Case report and literature review. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2011; 90 (3):116-200 - 28.

Zaubitzer L, Rotter N, Aderhold C, Gaiser T, Jungbauer F, Kramer B, et al. Metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma to the palatine tonsil. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2019; 10 (2):231-234 - 29.

Celebi İ, Bozkurt G, Polat N. Tonsillar Plasmacytoma: Clues on magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Medical Imaging. 2018; 18 (1):1-4