Abstract

Shrinking suburbs cause to occur several problems in Japan. One of the serious problems is the safety of communities, which are kept by community’s members. Some suspicious persons will invade vacancy houses, because nobody can maintain them. And it is difficult to keep house, because of aging of residents. And many public facilities and shopping centers were closed by the depopulation. This chapter introduces two case studies. One is the case of suburb of Hiroshima and another is Ryugasaki new town which is located in suburb of Tokyo. Amidst the aging in the suburb of Hiroshima, facilities for the elderly have been increasing in suburban housing estates in recent years. Facilities planned for child-rearing households and facilities developed for those households are no longer consistent with aging population attributes, and improvement of living convenience facilities and welfare facilities for the elderly is required. Therefore, this study focuses on the location of nursing care insurance service projects such as nursing home care and home care facilities, among welfare facilities for aged people in suburban housing estates, and examines the location of nursing care welfare facilities in the suburban housing estates of Hiroshima City. And we will point out the failure of Japanese town planning.

Keywords

- aging society

- housing estates

- town planning

- essential facilities

- welfare facilities

- Japanese cities

1. Introduction

The suburbs are not a dream location for every Japanese family, and depopulation has occurred in several urban regions. In many traditional urban growth models, suburbs continuously grow, with population inflow to commuter towns in metropolitan regions. However, this trend is changing, due to the population decreasing in old suburban areas, while the population in inner-city areas increases. Kubo and Yu [1] point that old Japanese suburban housing estates, which were developed before the 1970s, are in decline, and they have encountered several serious problems. The most serious are aging residents and a decreasing population, which are caused by long-term dwellings. As many Japanese think that the “Japanese Dream” is the occupancy of a detached house in a suburb, suburban Japanese residents tend to stay put after childrearing. Another serious problem is the increase in the number of vacant houses [2]. In this study, we attempted to clarify the conditions of shrinking suburbs in Japanese cities and introduce revitalization activities in the suburbs, with the aim of contributing to the revitalization of suburbs through geographical studies.

In Japan, there is little poverty and diversification in the suburbs. Aging, however, is a serious problem. Aging has resulted in an increase in the number of vacant houses and shrinking communities [1]. Regarding the aging of suburban residents in old housing, the first generation of migrants grew older and continued to live in their own houses in suburban areas. Furthermore, their children grew up and moved out. Therefore, aging communities without younger generations have formed in the suburbs. These were caused by the failure of town planning, which supplied the same types of houses for the short term [3]. Furthermore, increases in vacant houses are seen throughout old suburban housing estates, which induce new uneasiness, social troubles, and a drop in house prices. As a countermeasure, some suburban communities have attempted to vitalize and promote community activities.

Rapid population aging in modern urban societies has brought about significant changes in various aspects of social systems. In most metropolitan regions in Japan, suburban housing estates have aged rapidly in recent years. This is because, in the high economic growth period, a large number of monotonous houses without diversity in the layout and sales price zone were supplied in large quantities, and the life stage, age composition, and social position were almost homogeneous [1]. For this reason, in many suburban housing estates, the number of older persons increased, owing to the loss of the young generation (relative aging), and the total number of older persons increased, owing to the aging of residents (absolute aging). As these progressed in parallel, the aging state progressed remarkably.

The shrinking suburbs can cause several problems. One serious problem is the safety of communities, which is maintained by community members. Some people invade vacant houses because no one can maintain them. It is difficult to maintain houses because of aging residents. It is difficult to keep houses and gardens clean. Many public facilities and shopping centers have been closed due to depopulation. People must shop by bus or train. Although older adults depend on cars, they can no longer drive independently [3].

The suburban housing estates often assume the child-rearing generation as a resident at the beginning of development, and the facilities in the residential estates are educational facilities, such as kindergartens, child-rearing facilities, and elementary schools. Many commercial facilities are arranged systematically. However, owing to the aging of the residents, the number of children decreases significantly in elementary schools, empty classrooms occur, and commercial facilities with products for young parenting households in the center of housing estates are needed to respond to the needs of the old persons. There are also some places where shops close sequentially, and shutters are in place [1].

Amidst this aging trend, facilities for the old persons have been increasing in suburban housing estates in recent years. Facilities planned and developed for child-rearing households are no longer consistent with aging population attributes, and improvements in living convenience and welfare facilities for the old persons are required.

This study aimed to clarify the changes in suburban neighborhoods in Japanese metropolitan regions. In particular, we focused on aging and changes in family members to clarify the shrinking conditions of the suburbs. The second aim was to discuss how town planning caused these crises and how Japanese housing choices were made.

In the following sections, we present the results of an analysis of aging and regional transformation in suburban areas using two case studies: Ryugasaki City in the Tokyo metropolitan area and Hiroshima City in the regional metropolitan area.

2. Case study of Ryugasaki New Town

2.1 Development of Tokyo’s outer suburbs

After World War II, the Japanese government established national land-planning regimes in the 1950s. First, a hierarchical decision-making structure for planning (national, regional, and prefectural land planning) was developed to reconstruct urban infrastructure and overcome housing shortages. In the 1960s, a series of national land-planning and related policies were designed to stimulate rapid industrialization and urbanization, not only in the three major metropolitan areas but also in newly designated industrial areas, to form industrial clusters throughout Japan. At the same time, transportation systems (e.g., highway networks, bullet trains, nationwide train systems, and airport networks) were intensively established, resulting in the growth of major large-city networks connected by management functions (e.g., the network between head offices in Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya and their regional offices in Sapporo, Sendai, Hiroshima, Okayama, and Fukuoka). Under these circumstances, the rapid inflow of younger workers into major cities required new frontiers to accommodate them. As a result, suburban development has increased since 1980, peaking in the 1980s, just before Japan’s economic bubble burst.

In terms of housing development to overcome housing shortages and accommodate newly migrated workers to large cities, the Japan Housing Corporation (presently the Urban Renaissance Agency) played a significant role. To supply a sufficient number and quality of housing in a short period, the Japanese government launched the Housing Loan Corporation (1950), enacted the Public Housing Law (1951), and established the Japan Housing Corporation (1955). The Housing Loan Corporation supported housing purchases by high-income populations and the Public Housing Law supported young couples and nuclear families in offering affordable rental housing units. The Japan Housing Corporation was responsible for huge suburban housing developments; usually, these included detached houses, rental housing units, and shopping streets, and many of them learned from the planning ideas of neighborhood units. In one catchment area of an elementary school, a neighborhood unit, community center(s), shopping and office areas, and a variety of housing were developed. Each facility and housing area was connected by pedestrian roads separated from automobile roads. In Osaka, Senri New Town (NT) has welcomed new residents since 1962, followed by Kozoji NT in Nagoya in 1968 and Tama and Narita NTs in Tokyo in 1971. Similar suburban developments were popular between the 1960s and the early 1990s. In addition to public agents (Japan Housing Corporation and prefectural housing corporations), private housing developers joined the suburban housing supply, reaching a home-ownership rate of 60% in Japan in the 1960s [4].

2.2 Case study of Ryugasaki New Town

Using the case study of Ryugasaki NT, which has been developed by the Former Japan Housing Corporation since 1981 at the edge of the Tokyo metropolitan area, we explored the possibilities for suburban neighborhoods to be sustainable residential areas.

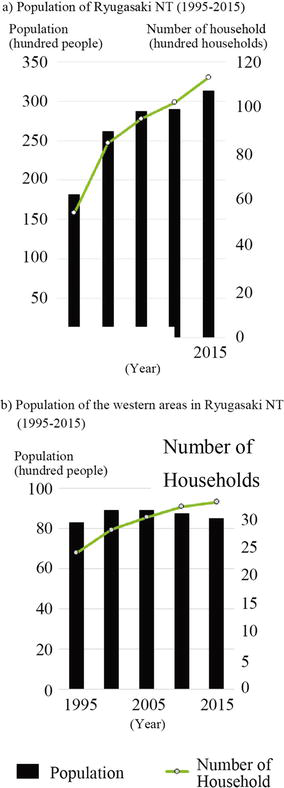

In 1981, the western half of NT was completed and occupied by thousands of residents commuting to central Tokyo, whereas the eastern half was under construction. After four decades, the western half of NT is now occupied by elderly couples or singles, turning them into super-aging neighborhoods, along with the outmigration of the younger generation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in population and households in Ryugasaki NT (1995–2015). Source: Population Census of Japan (1995–2015).

According to our field survey, slight but constant inflows of foreigners, renters, and buyers of existing houses contributed to maintaining the population in the western half of the NT. However, the eastern parts of NT took more than 15 years to complete until the municipal government changed its main area from residential or industrial to commercial in the late 1990s. After the opening of a new shopping center in the mid-1990s, the surrounding residential areas were purchased by relatively younger families who worked and studied in neighboring cities. Ryugasaki NT complemented the residential function of the Tokyo metropolitan area in the 1980s and the 1990s, but gradually weakened this function. Now, NT supplements the strong housing demand of local, mainly blue-collar residents. Such a transition in the major functions of NT helped make an aging suburban housing estate a sustainable residential area. The details are presented in the following sections.

2.3 Changes in the residential characteristics of Ryugasaki NT

We conducted questionnaire surveys in Ryugasaki NT in May 2021 and distributed them to all the households in the NT on behalf of all community centers there; 11,719 questionnaires were distributed, and 2130 valid answers were collected (18.2% of respondents). We compared valid answers between the eastern and western areas.

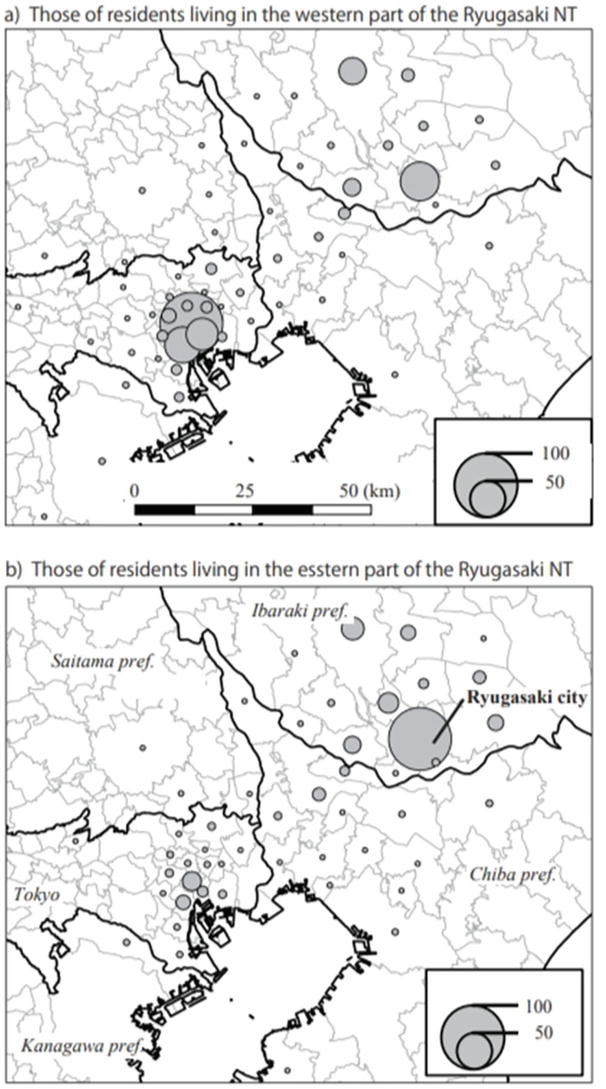

Figure 2 shows the locations of the major workplaces of household heads in the two areas of the NT. In the western area, most household heads worked in central Tokyo, whereas Ryugasaki and its neighboring cities became remarkable in the eastern parts of the NT. In our questionnaire surveys, a large proportion of Western residents searched for their homes when they married, had babies, or felt a shortage of housing space because of the growth of their children in a large part of the Tokyo metropolitan area. Due to rising house prices at the time, they had to give up on the idea of purchasing housing in the near suburbs (10–30 km commuter belt of Tokyo).

Figure 2.

The location of the offices to which household heads worked for longest. Note: In the western part of the NT (top figure), out of 567 answers from residents of this area, 309 were listed on the map. In the eastern part of the NT (bottom figure), of the 232 answers from residents of this area, 217 were listed on the map. Locations outside of the map were excluded. Source: Authors’ questionnaire surveys.

Meanwhile, with a decline in house prices in the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century, residents of the eastern part of the NT could find affordable housing options in Ryugasaki NT. At that time, the former Japan Housing Corporation stopped new housing developments and was one of the rare developers that offered total planning for the NT area. They had plans for built environments and facilities to satisfy residents’ daily needs (e.g., shopping, recreation, education, communication among residents, or medical treatment). Private developers tend to sell only houses and land. Therefore, most residents tended to live and work in neighboring areas and evaluated the residential environment of Ryugasaki NT.

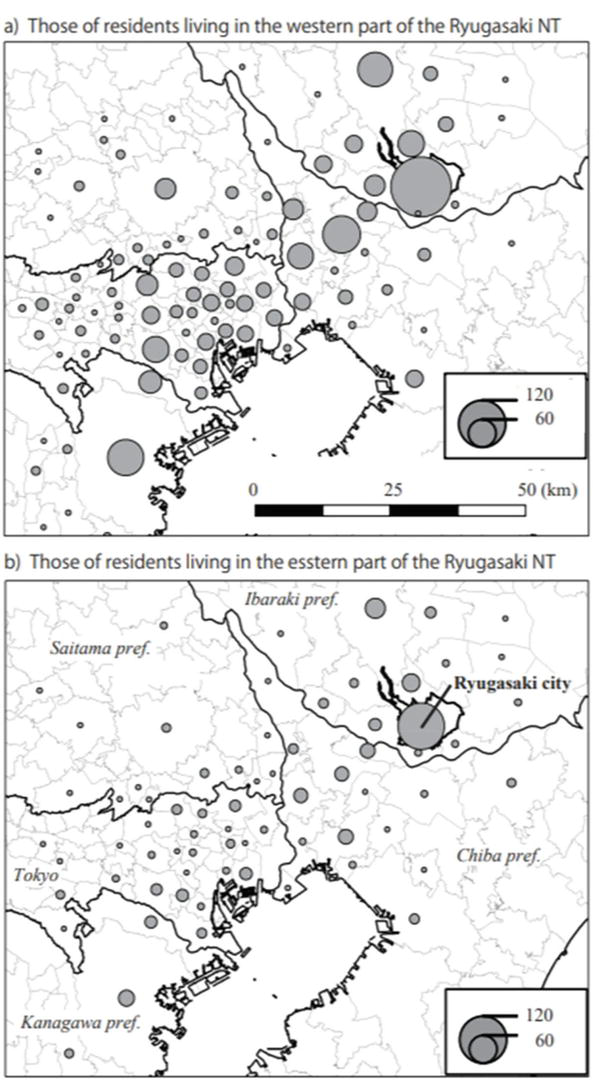

The residential areas of adult children clearly reflected the differences between the two areas (Figure 3). In the western part of the area (top figure), a large proportion of adult children lived in Tokyo, followed by those living in neighboring areas of their parents. In addition, many adult children maintained a double-income status and worked in offices in central Tokyo or nearby suburbs. By contrast, in the eastern areas, most adult children lived nearby and maintained a double-income status.

Figure 3.

The residential areas of adult children. Note: In the western part of the NT (top figure), out of data from 1034 adult children residents of this area, 861 were listed on the map. In the eastern part of the NT (bottom figure), among the 361 adult children residing in this area, 330 were listed on the map. Locations outside the map and adult children living with their parents were excluded. Source: Authors’ questionnaire surveys.

In summary, the western area is characterized by typical suburban residents from the 1970s to the 1980s, mostly single-income households working in central Tokyo supported by housewives. However, the eastern area is characterized as a great housing option for residents who live and work in neighboring areas. Ryugasaki NT is part of the Tokyo metropolitan area, compensating for residential functions during the rapid growth period from the 1980s to the 1990s. In the period of the urban divide and shrinking suburbs in the first two decades of the twenty-first century [5], Ryugasaki NT played the role of a center for neighboring cities, offering superior housing options to other small and partial housing developments.

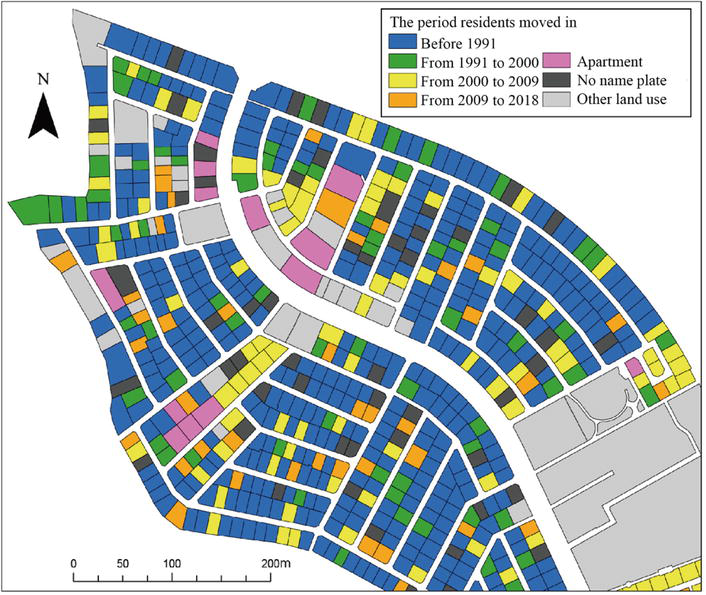

3. Constant inflow of residents to avoid aging and shrinking neighborhoods in Japan

We have confirmed that western and eastern areas within Ryugasaki NT had different urban functions, reflecting the different economic and urban conditions between 1970 and the 1990s and the first two decades of the twenty-first century. In the Japanese housing market, most of the shrinkage in the outer suburbs was triggered by the aging of the whole neighborhood due to the aging of existing residents and outflows of younger generations under the fragile existing housing market [6]. Therefore, we examined the inflow of new residents in a district in the western area (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The time period when residents moved into a neighborhood in the western part of Ryugasaki NT (1991–2018). Note: We determined the time period for residents moving into the residence using name plates written on residential maps. If name plates were renewed between the two time periods, we judged that the resident moved between that time period. Source: ZENRIN Co. Ltd., Residential Maps, Ryugasaki City (1991/2000/2009/2018).

According to the interview surveys, a significant number of residents moved out when the “Building Agreements” of this neighborhood were not renewed. In Ryugasaki NT, most of the neighborhoods established “Building Agreements” to maintain pleasant residential environments, but some neighborhoods forgot to renew, gave up renewing due to the lack of agreement from residents, or modified the contents to meet today’s needs.

In this case neighborhood, the renewal of “Building Agreements” was not successful and caused an outflow of residents. The vacant housing was occupied by new residents, and the constant and slight inflows of new residents have continued today. Although the neighborhood is aging, these constant inflows prevent complete shrinkage.

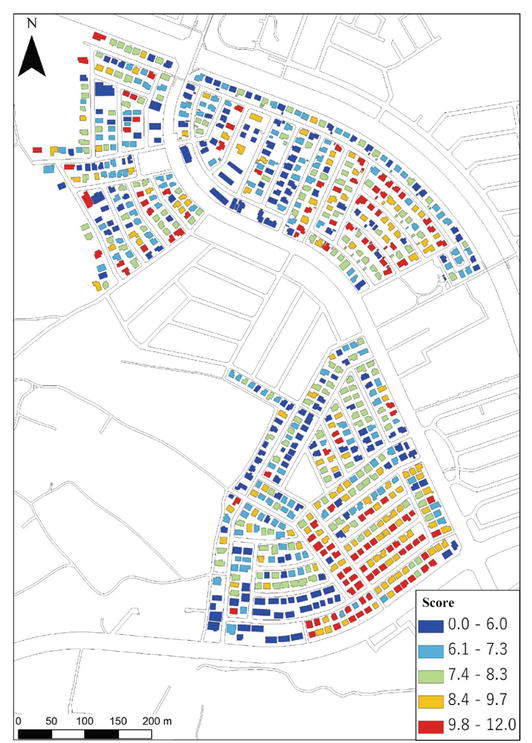

To calculate the quality of the residential environments of the case neighborhood in the western area of the Ryugsaki NT, we conducted a field survey to determine the condition of each house and its site based on two criteria, “Building Agreements” and contemporary and universal design requirements. Details of the calculation and content are explained in the notes for each figure. There was no significant correlation between these two criteria.

According to the score distribution based on “Building Agreements,” only southern blocks showed a high score (Figure 5). These blocks are occupied by education-minded volunteer residents (according to interview surveys). In addition, these blocks face the elementary school across the road, therefore many houses had security signs (e.g., signboards, stickers, or flags), such as “don’t rush into the road” or “be careful of crime.”

Figure 5.

The score distribution based on the “building agreements” of the case neighborhood (2021). Note: The “Building Agreements” of this case neighborhood were considered for (1) land use (maximum 4 points: Detached house (4) and others (0)), (2) trees and planting (maximum 4 points: Based on the number of trees in the garden), and (3) external structure (maximum 4 points: Tree material (2), other plants (1), others (0); height is 150 cm or lower (2) and over 150 cm (0)). Source: Authors’ field surveys conducted in March 2021.

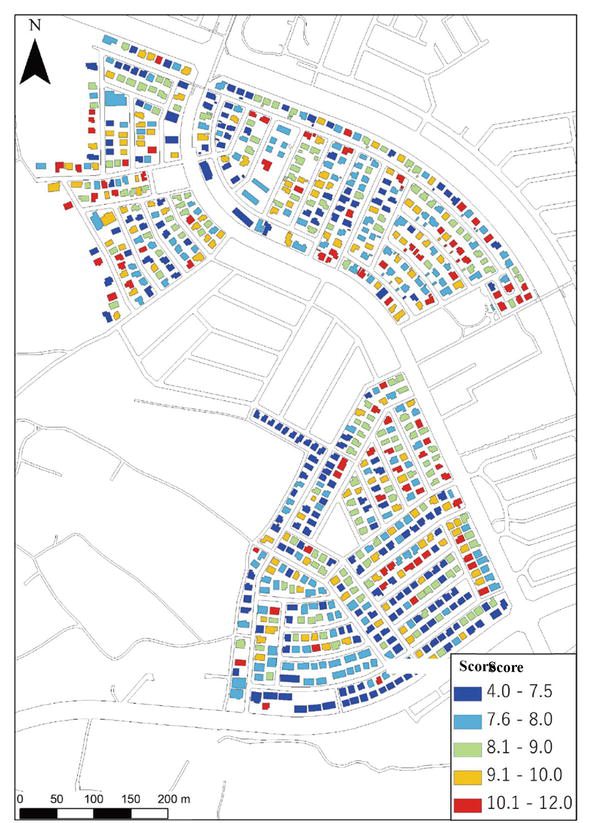

With regard to more contemporary needs (more than two parking spaces) and universal design guidelines (no barriers between the road and entrance of the house), the northern blocks showed high scores (Figure 6). Essentially, the blocks with a high score in the “Building Agreements” criteria received a lower score here. High-scoring blocks are occupied by newly moved residents or renovated houses; therefore, they have sufficient parking spaces and fewer barriers between the road and entrance. Due to the fragile existing housing market of Japan, new ideas, such as “barrier free” environments, can be seen regularly in newly built houses but not in existing houses. Homeowners who require new facilities must continue investing in their homes to meet their residential needs. The fragile housing market can affect people’s decision to move to new houses because of the lower possibility of missing out on the house. In this way, old suburban neighborhoods gradually lose attraction to the next generation.

Figure 6.

The score distribution based on requirements for universal design (2021). Note: The score was calculated using the following: (1) No barrier between the road and the housing site (maximum 4 points) and the site to the entrance of the house (4), based on the formula of “4-(number of steps)/2,” if the number of steps exceed 8, the score is 0, but we add 2 points if there are handrails for overcoming the barrier; and (2) the number of parking spaces (formula is “the number of parking spaces*2, with a maximum 4 of points). Source: Authors’ field surveys conducted in March 2021.

Thanks to the booming developments in eastern areas, western parts can be another option for homeowners seeking affordable but well-designed suburban developments. Good residential environments with classical or contemporary designs can satisfy various needs. The case neighborhoods showed the possibility of becoming sustainable neighborhoods in the near future.

4. Aging and changes of essential facilities in housing estates in Hiroshima

In the next case study, we focused on the location of nursing care insurance service projects such as nursing home care and home care facilities, among welfare facilities for older persons in suburban housing estates, and examines the location of nursing care welfare facilities in the suburban housing estates of Hiroshima City [2]. And we will point out the failures of Japanese town planning. As suburban housing estates were originally targeted at child-rearing households, they were rarely established from the very beginning at the time of the development of welfare facilities for older persons. However, owing to the aging of residents, the long-term care insurance service business is now more likely to be located in suburban areas [1].

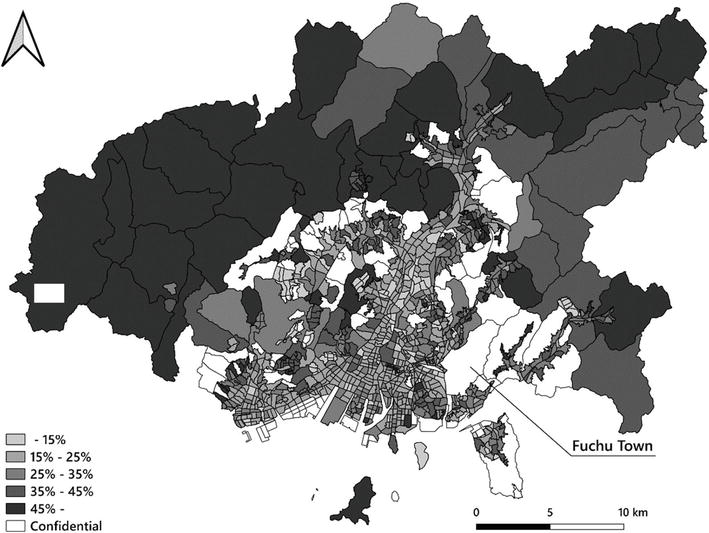

4.1 Aging in suburban housing estates

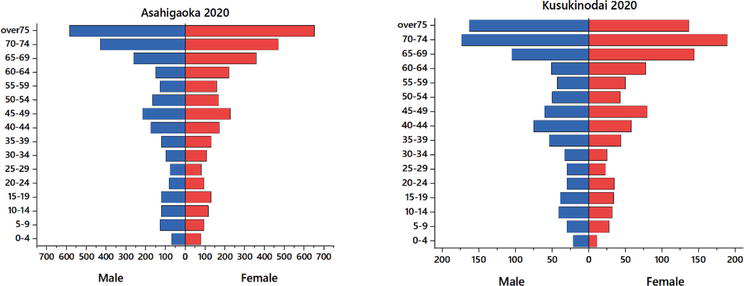

Suburban housing estates have rapidly lost their appeal since the 1990s, with potential homeowners showing preference for condominiums in city centers [6]. Suburbanization has continued, and suburbs have started to shrink due to changes in the urban housing market and lifestyles. Hiroshima City has become a typical phenomenon in which the population of suburban housing estates is aging. Figure 7 shows that many older persons live in suburban housing estates. In the old suburbs, the majority of residents have become elderly, and the most popular family type has only one or two members [1].

Figure 7.

Rate of older persons in Hiroshima City (2020). Data: National Census.

During the early stages of development, the residents’ age structure indicated that young nuclear families were dominant. Thirty or forty years later, the household couple aged and their children moved out (Figure 8). In these old housing estates, the number of children has decreased significantly and kindergartens and daycare centers for children have been closed. As Yui (2019) pointed out, owing to the outflow of young people and an aging population, shopping streets within suburban housing estate are closing, and the number of vacant houses is increasing. As a result, seniors have started going out to shop outside the area and using home delivery services to purchase food.

Figure 8.

Age structure in old suburban housing estate in Hiroshima City.

4.2 Changes of essential facilities

As Kubo and Yui [1] clarified, some buildings have been changed from supermarkets to nursing homes for the older persons. The number of large nursing homes for the older persons is increasing in the suburbs. As the population declines and ages, it has become difficult to maintain shopping malls, and many are closing. Nursing homes for the older persons are located in the suburbs because of the aging population [2]. Aging is proceeding in the inner-city and suburbs. In particular, the number of nursing homes for the older persons is increasing in suburban areas because their children live in distant places and cannot care for their parents. In response to the aging population, welfare institutions for the older persons have increased rapidly in suburban residential areas in recent years. Both home nursing care service offices and nursing home care service offices are widely distributed in residential areas in the suburbs.

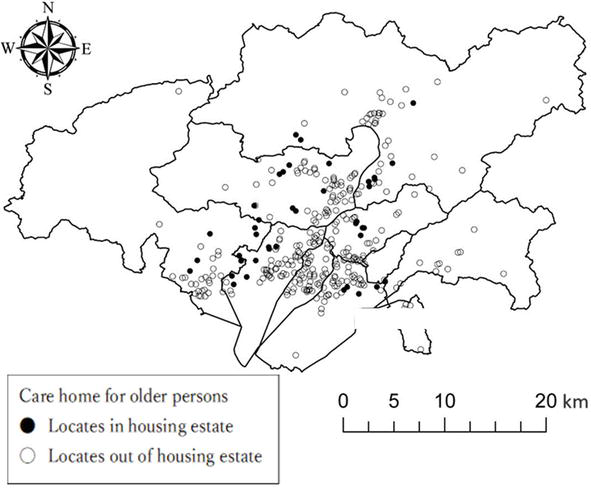

Yui [2] clarified that nursing homes for the older persons are located in the suburbs because of the aging population (Figure 9). Aging is proceeding in the inner-city and suburbs. In particular, the number of nursing homes for the older persons is increasing in suburban areas because their children live in distant places and cannot care for their parents. Some buildings have been changed from supermarkets to nursing homes for the older persons. The transformation of shops to welfare facilities is often observed in suburban areas. Otherwise, the number of large nursing homes for the older persons is increasing in the suburbs. Some vacant houses have been renovated into welfare facilities or cafés where the older persons gather each day.

Figure 9.

The locations of nursing home for older persons in Hiroshima (Reprinted from [

5. Conclusions for a sustainable community

Aging in housing estates was induced by the failure of town planning, which provided a monotonous housing type in the short term. Aging is caused by the aging of the first generation of migrants, and a high rate of aging is caused by the moving out of the second generation. Furthermore, serious aging is caused by residents’ homogeneity across generations because of the period of a housing supply shortage [1, 7]. The housing preferences of young households changed from the suburbs to inner cities. Working women prefer urban residences in order to balance their work and home lives. Thus, gentrification is related to female working conditions. Housing projects try to develop conditions to provide care facilities for the older persons and to enable workers to balance the demands of work and family and, furthermore, they are able to make use of women’s abilities in the old neighborhoods. These housing projects attempt to develop conditions that provide care facilities for the older persons and enable workers to balance the demands of work and family. It is necessary to set the period of housing development to more than 20 or more long years. Furthermore, it is also important to plan the mixed development, which supply for various households.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Toyota Foundation (D19-R-0007: PI is Tomoko Kubo) and JSPS (23H00730: PI is Tomoko Kubo). We would like to express my gratitude to those who contributed to this project: Dr. Yuki Iwai and Mr. Haru Usui at University of Tsukuba. We thank Mr. Satoshi Yokogawa and Mr. Taketo Onitsuka for the drawings maps and graphs at Hiroshima University.

References

- 1.

Kubo T, Yui Y, editors. A Rise in Vacant Housing in Post-Growth Japan: Housing Market, Urban Policy, and Revitalizing Aging Cities. Singapore: Springer; 2019 - 2.

Yui Y. Increasing welfare services and feature of uses in aging suburban housing estates. Annals of Japan Society for Urbanology. 2018; 51 :169-176 - 3.

Yui Y, Sugitani M, Kubo T. The housing vacancies in suburbs: A case study of Kure City. Urban Geography of Japan. 2014; 9 :69-77. DOI: 10.32245/urbangeography.9.0_69 - 4.

Ronald R. The Ideology of Home Ownership. New York: Palgrave Macmilan; 2008 - 5.

Kubo T. Divided Tokyo: Disparities in Living Conditions in the City Center and the Shrinking Suburbs. Singapore: Springer; 2020 - 6.

Hirayama Y, Izuhara M. Housing in Post-Growth Society: Japan on the Edge of Social Transition. New York: Routledge; 2018 - 7.

Kubo T, Yui Y, Sakaue H. Aging suburbs and increasing vacant houses in Japan. In: Hino M, Tsutsumi J, editors. Urban Geography of Post-Growth Society. Sendai: Tohoku University Press; 2015. pp. 123-146