The appearance of the words equity, equality, and parity in KCSE exams.

Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals have long underscored the significance of equity as a value-laden concept. This study explores the concept of equity through an examination of secondary school leaving examinations in Kenya. The analysis incorporates examination data from 2018 to 2022 across three subjects: History and Government, Christian Religious Education (CRE), and Business Studies. The analysis specifically investigates the treatment of various topics related to equity, revealing a substantial emphasis on issues of economic disparity in comparison with themes such as ethnicity, gender, and race. Notably, the analysis within the realm of CRE illuminates distinctions in moral perspectives between the West and Kenya, with Kenya’s highly capitalistic economy not necessarily aligning with a strong endorsement of liberal competition in examinations. Despite its capitalist orientation, Kenya’s approach to welfare in exams transcends the mere alleviation of those below a certain threshold; it delves into the fundamental issue of difference itself. This chapter contends that Kenya’s conceptualization of equity diverges from Western definitions, positing its unique notions of justice and fairness, with a predominant focus on fostering social equality through social welfare and mutual assistance.

Keywords

- equity

- secondary school leaving examinations

- Kenya

- social equality

- economic differences

1. Introduction

The term “equity” has become a frequent topic in discussions surrounding the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly since 2015. However, its interpretation varies across societies and nations [1]. Distinguishing itself from concepts like “equality,” the term is closely aligned with ideas of justice and fairness [2]. Concepts of justice and fairness, often explored in literature on citizenship and religious education, lack a universally agreed-upon international definition. Studies have highlighted disparities in the reception of these concepts between Western and non-Western countries [3, 4, 5, 6]. Therefore, comprehending the notion of “equity” requires an understanding of its local perceptions and the varying interpretations of justice and fairness across countries and societies.

Defining “equity” poses challenges, and its societal interpretation remains elusive. Notably, there is a dearth of studies investigating the definition of “equity” with Africa as a focal point. Considering the significance of “equity” as a key international development goal, its impact on African nations should not be underestimated. Hence, this study seeks to fill this gap by examining how the concept of “equity,” integral to international goals, is embraced in African societies. Specifically, the research suggests that exploring the teaching of justice and fairness in schools, particularly in three humanities subjects in Kenya—business studies (BS), Christian Religious Education (CRE), and History and Government (HIS)—may reveal a country’s stance on equity.

The study aims to analyze how these subjects impart concepts related to equity and other values. To this purpose, first, the words related to equity are to be identified based on the frequency with which they are used and with what words and topics they are associated. Then, it will explore how the state of difference is perceived and what corrective measures are considered desirable.

2. Literature review

Education about fairness and justice in schools globally, including Africa, often aligns closely with moral education. Various African countries, such as Zambia, Malawi, and South Africa, incorporate moral education into subjects like “spiritual and moral education,” “religious and moral education,” and “life orientation” [7]. Religious education plays a significant role in moral education in several countries [8], although conflicts with its practice [9, 10] and conflicts between religion and morality [11, 12] have been noted.

The historical background reveals that in many African countries, religious education primarily focuses on specific religious tenets, such as Christianity or Islam, rooted in the colonial legacy [3]. In Nigeria, moral education has long been intertwined with religion, mainly Christianity and Islam [13]. However, Matemba [3] critiques religious education in Africa as a colonial project heavily influenced by missionaries and European powers. Some countries, like Botswana, have addressed curriculum reform challenges by excluding religious education and incorporating issues and values specific to Africa into their educational content [7]. Even decades after its introduction, moral values in Christian/Islamic religious education do not always align with moral values in Africa.

Citizenship education in Africa presents conceptual discrepancies when compared to Western contexts. The distinction between the “civic public” and the “primordial public” of ethnic groups in Africa, where individuals often identify with the latter public sphere, is notable [5]. Countries with diverse ethnic groups tend to prioritize nurturing national citizenship, a different trend from nourishing global citizenship identity in Western countries [14, 15]. The contrast between individualism in the West and communalism in Africa is evident, with local norms of solidarity like Ubuntu/Harambee in Kenya [16]. These differences, highlighted by Bhola [6], underscore tensions between Western and non-Western understandings of the link between citizenship and development. These variations suggest that the image of a desirable society and the notions of fairness or justice may differ between the West and Africa, leading to diverse interpretations of “equity.”

Reviewing the studies reveals that Western and African conceptions of morality may not necessarily align. In citizenship and religious education, including moral education, inconsistencies arise when Western concepts are imported into African contexts. These discrepancies result from the influence of various conditions in existing societies, leading to different levels of acceptance. Similarly, the acceptance of equity, encompassing concepts such as justice and fairness, is influenced by various societal conditions. Therefore, examining how these concepts are recognized, accepted, and reconciled with existing ideas of justice and fairness in society is crucial.

3. Analysis subjects

3.1 Kenyan context

In this study, Kenya serves as the analyzed country for several reasons. Firstly, English is the official language and the language of instruction in Kenyan schools, facilitating the examination of “equity” and related international concepts. Secondly, Kenya typifies an African nation with diverse ethnic groups and a colonial background, contributing to distinctions in citizenship education between the West and Africa. Finally, the prominence of religious education, encompassing Christianity and Islam, aligns with the framework explored in prior studies.

Major challenges faced by Kenya post-independence revolved around unifying a nation with diverse ethnicities. The curriculum initially emphasized promoting nationhood, national integration, social equality, Kenyan identity, and building inclusive citizenship [16]. Despite the introduction of the subject of “social education and ethics (SES)” into the school system in 1976, since the 1990s, the Kenyan government has downgraded the status to an optional subject with religious education from compulsory secondary school subject for 2 years. Then, religious education gained more power through the efforts of religious leaders. Finally, by 2003, SES was removed from the secondary education curriculum [16].

These facts will show the challenges in citizenship education in Kenya (how to be a Kenyan unity in a country where several ethnic groups live) and the fact that Christianity and other religions have no small political power. It shows the relevance of choosing Kenya as a case analysis of Africa in comparison with the West for this study, which seeks to analyze various concepts of equity.

3.2 Overview of the education system

In this study, the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education examination (KCSE exam) was treated as the object of analysis. The reason for targeting examinations for analysis is that they are prepared by the Kenyan government and are texts that are read by almost all students. While analysis of textbooks and interviews with teachers may be appropriate, textbooks are not the best source for detecting the Kenyan government’s attitude toward equity because, in the case of textbooks, the publisher is the intermediary between the students and the government and because there are multiple textbook companies. Similarly, the interviews with individual teachers would also be influenced by their personal views and the issues surrounding the students. On the contrary, the examinations are the best for analysis in the sense that they are common throughout Kenya and are produced by the government.

The KCSE was introduced in 1989. In 2018, Kenya had a gross enrollment rate of 104.0% for primary education (which lasts 8 years) and 70.3% for secondary education (which lasts 4 years) [17]. About half of all students enrolled in primary school take the KCSE, which is the final examination of 12 years of education. It should also be noted that in Kenya, English was adopted as the language of instruction in Grade 4 primary schools in 1961 [18], and all curricula and examinations were written in English, except for examination papers in languages other than English.

Kenya is currently going through a period of transition, with the new curriculum being introduced and the old curriculum coexisting. The old curriculum, which was introduced in 1984, was replaced with the new curriculum, published in 2017. As of the academic year 2022, the new curriculum is reflected up to the seventh grade. Therefore, the KCSE exams from 2018 to 2022, which were the subjects of this analysis, were based on the old curriculum.

Examinations in the three subjects of HIS, CRE, and BS were used for this study from 2018 to 2022. As of 2019, the KCSE exam has 30 subjects, but only 11 of them are taught in most schools and are usually chosen by students in the exam. Each candidate chose 7 or 8 subjects for examination, and these 11 subjects were chosen from at least a quarter of all candidates. Three subjects, HIS, CRE, and BS, were chosen for analysis due to their relevance to the study of “equity.”

The KCSE is mostly a descriptive examination. Many questions have multiple correct answers, and candidates are required to give the number of answers specified in the question. This analysis deals with question and answer sets and will primarily refer to multiple-description model answers. KCSE Examination Report, published annually by the Kenya National Examination Council, contains question texts, model answers, and Marking Schemes. In this study, these data were used in the analysis.

4. Results

4.1 Three subjects

4.1.1 Frequency of “equity” terms

Initially, the study examined the frequency of terms related to “equity,” encompassing variations like “equality” and “parity,” in three subjects over 5 years. The analysis revealed that in History and Government (HIS), “equity” appeared five times, “equality” seven times, and “parity” once. In Christian Religious Education (CRE), “equity” occurred once, “equality” five times, and in Business Studies (BS), “equity” surfaced seven times, “equality” three times, and “parity” twice (Table 1). The collective instances of “equality” surpassed those of “equity,” with minimal occurrences of “parity.”

| Equity | Equality | Parity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 7 | 1 | |

| 1 | 5 | 0 | |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | |

Table 1.

Note: HIS, History and Government; CRE, Christian Religious Education; BS, Business Studies.

“Equity” was consistently linked to “distribution” (or share, tax) across all subjects during the study period, appearing alongside words like “sharing” 12 out of 13 times. Notably, in a 2019 BS question about the characteristics of a good tax system, “equitably distribution of the tac (tax) burden according to the payer’s ability to pay” was considered a model answer.

The term “equality” was employed from two main perspectives. One concerned the equality of treatment—for example, equality before God or equality before the law—which was expressed in terms of equality regardless of gender, race, and so on. The other was guaranteeing equal opportunities; for example, equal job opportunities and equal distribution of resources were mentioned more than once.

The number of appearances of “parity” was limited compared to other words. The word “parity” showed up in all of them as the word “disparity,” and in all of them, it was frequently used in association with “income.” In two of them, it was related to “distribution,” as was “equity” and “equality.” For example, the answer to the question “feature that may indicate a country’s state of underdevelopment” included “high disparity in income distribution” BS in 2019.

4.1.2 Topics regarding “equity”

Gender, ethnicity, religion, race, origin, and region were among the topics covered, along with various words related to equity, with gender and ethnicity appearing more frequently than other topics. As for ethnicity in CRE, the question in 2019 asked about “ways in which Christians can reduce tribalism in Kenya today,” and the model answers include “by preaching/teaching on equality/oneness of human being before God” and “by urging the government to ensure equal distribution of national resources.” However, religion, disability, and region are rarely addressed. Additionally, those were cases that appeared in questions of historical facts or when listing pluralities, such as “regardless of…,” which seemed to be treated less than other themes.

There were 22 model answers related to discrimination, 7 of which are references to discrimination from the West against Africa or discrimination based on colonial policies, apartheid, etc., all found in HIS. For example, under the theme of race, most questions were related to other countries, such as Senegal (HIS in 2018) and South Africa (HIS in 2018), and an explanation of its historical background HIS in 2021. For example, in the context of Kenya, “the desire to create a society free from inequality/oppression/racism” was a model answer to the question “give one reason for the adaptation of the African Socialism in Kenya” (HIS in 2021), which was mostly about the past and less about Kenya today. Many of the discussions on race were about past facts and policies of other countries, as mentioned in many of the HIS, but there was a high level of interest in such historical facts contrasting the West and Africa.

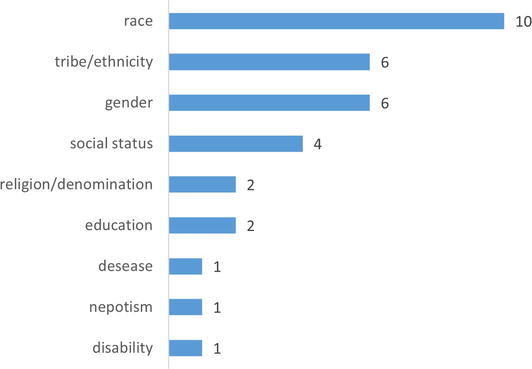

For the other 15 model answers related to discrimination, the denial of discrimination in business and morality was indicated in all three subjects. The most common groups associated with the term discrimination are descriptions of race, followed by gender and tribal/ethnic discrimination, with six mentions (Figure 1). The other three subjects mentioned were social status (four times), and religion/denomination and education (two times), while disease, nepotism, and disability were mentioned once each. The high number of references to gender and ethnicity is consistent with the points made at the beginning of this section, indicating a high level of Kenyan interest in these topics.

Figure 1.

The appearance of the topics related to discrimination. Note: created by the author.

Difference is described as a potentially destructive factor in traditional African communities. For example, “economic factors/poverty/wealth/social status” (CRE in 2018) was a model answer to “identify six factors that have affected the kinship ties in the traditional African communities.” “Due to tribal/ethnic barriers whereby some do not help those who belong to other communities” (CRE in 2019) was a model answer to the question “give seven reasons why some Christians find it difficult to help the needy.” Despite denying discrimination, diversity within a community may also be identified as a factor hindering communalism.

To resolve these issues, there was an emphasis on the need for distributing resources to eliminate undesirable circumstances (e.g., inequality) related to these topics, as well as a recognition of the equality of all people. In particular, content addressing economic differences was dealt with extensively in all three subjects. For example, in HIS, where “African Socialism” is studied, African socialism was positioned in the 2018 exam questions as one of Kenya’s national philosophies, alongside “Harambee” and “Nyayoism.” In the HIS in 2019, there was a question, “discuss five features of African Socialism which was adopted in Kenya after independence.” The answer includes perspectives related to equality, such as “it emphasized equal job opportunities for all regardless of one’s tribe/religion/background,” and perspectives related to welfare and redistribution, such as “narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor would be achieved through progressive taxation/mutual assistance” [19].

In connection with this, tax and distribution were mentioned frequently in HIS and BS. For instance, BS is often asked about understanding the benefits, drawbacks, and features of tax systems; however, the answers to these questions are related to equity [19]. For example, in 2018, when asked about the advantages of indirect taxes, the answer included “it promoted equality/paid by everyone who purchases the goods.” Furthermore, a model answer to the question “Explain five demerits of indirect taxes” in 2021 was “less equitable/regressive/unfair as the burden falls heavily on the poor who spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption” (BS in 2021). Conversely, in 2019, “equitably distribution of the tac (tax) burden according to the payer’s ability to pay” is an answer to the question, “characteristic of a good tax system” as noted in previous section. A view of the distinction between equity and equality in terms of the tax system may be obtained by comparing these expressions [19].

Questions dealing with “poverty” and “gap between wealth and poor” as problems to be solved were particularly common in HIS, and the value of helping the needy and the criticism of being greedy was overwhelmingly asked in CRE. For example, in CRE, a question posed in 2018 regarding “similarities between traditional African view of evil and Biblical concept of sin,” included “greed” as the possible answer. Many questions in CRE focus on Biblical content, but they are not limited to that; for instance, in 2018, a question asked: “factors that have led to an increased role of child labour in Kenya,” with the answer being “greed for money by the child’s parent/guardian” and “gender discrimination in some communities/boys preferred/given priorities than girls.” On the other hand, generosity and sharing with others were also questioned as essential values, both from the perspective of God’s teachings in Christian and African communities.

4.2 CRE as moral education

Of the three subjects, CRE prominently featured words related to “equity” accompanied by value judgment. Previous studies suggest that religious education significantly influences moral development. Manea [20], who analyzed the impact of religious education, indicates that a survey of teachers suggested that religious education in schools is likely to shape students’ moral behavior and conscience. Therefore, this section delves into CRE, examining how the concept of “equity” is taught.

4.2.1 CRE in Kenya

Immediately after independence, CRE was integrated into the curriculum to help students gain spiritual, social, and moral insights into a rapidly changing society [21]. CRE is suggested not only as a subject but also as a moral/religious practice [22]. According to a 2023 syllabus, one of the general objectives of CRE is to acquire “social, spiritual and moral insights to think critically and make appropriate moral decision in a rapidly changing society.”

In Kenya, Christians make up 78% of the population, which is categorized as Protestants, who account for 45% of the population, and Roman Catholics, who comprise 33% of the population. There are also Muslims, 10% of the population. Muslims are often compelled to opt for CRE because of a lack of human resources and teaching materials in secondary school subjects, even though Kenya offers Muslim religious education as a curriculum and examination subject [23, 24]. Students study religious education as a compulsory subject until the second grade of secondary education, which consists of 4 years, and opt for an optional subject from the third grade. Nearly 80% of candidates chose CRE as an optional subject for the examination at the end of secondary education.

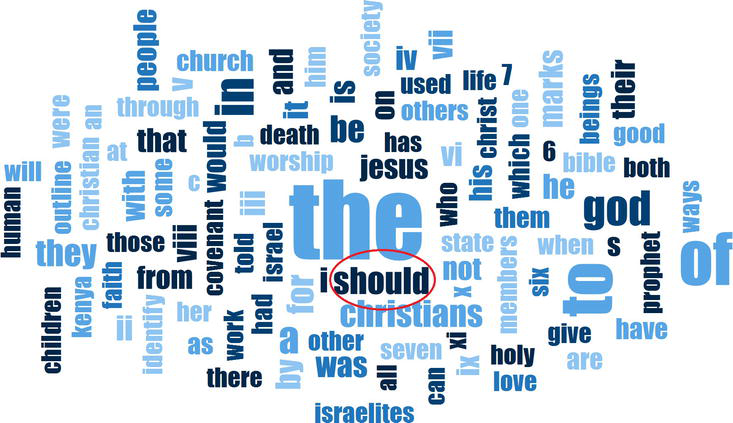

Regarding the characteristics of the examination, the questions are not necessarily limited to knowledge about Christianity and include environmental problems, plastic surgery, community initiation and traditions, marriage and divorce norms, and alcohol abuse. Examples require enumerative and descriptive answers. The questions and model answers frequently include words with value judgments regarding justice and fairness. For example, the word “should” has been frequently used (Figure 2). It appeared 197 times in 5 years of examinations and is the eighth most used word among all words involving prepositions, such as “the,” “a,” and “to.” A model answer was that “wealth should not be used to buy unnecessary materials for luxuries when others are suffering” (2018). Further, there are numerous words expressing value judgments such as “good” (35 times), “evil/evils” (25 times), and “false” (10 times). This appeared in the question “give five examples of relationships based on false love in Kenya today” (2022).

Figure 2.

Frequent words in CRE exam questions and model answers for 2018–2022. Note: Created by MAXQDA and modified by the author.

4.2.2 Attitude toward diversity

In this section, topics that received particular attention are reviewed to confirm attitudes toward each topic in the CRE. First, there were critiques on neoliberalism, which can be expressed with words such as “greed,” “selfishness,” “materialism,” “competition,” and “wealth accumulation without proper distribution.” However, poverty is an issue that needs to be resolved through voluntary distribution. For example, “the advocates for equal distribution of resources” (2020) was a model answer to the question “give ways in which the church is promoting social justice in Kenya today.” “Wealth should be used to help the needy in society” (2020) was also one model answer to the question “outline the traditional African understanding of wealth.”

Furthermore, there was an emphasis on the importance of sharing/helping. The word “share” appeared seven times, and the words “help” appeared 42 times in 5 years of examinations. For instance, “Christians should help the needy/widows/orphans” (2018). It can be said that the differences between the West (individualism/materialism) and Africa (communalism), as pointed out in Obiagu [4], have been identified, and the latter is portrayed favorably, in contrast to the former.

Regarding to the attitude toward gender, essentially, there was an emphasis on equality between men and women, such as the expression “man and woman are equal before God” (2018), which is a model answer to the question “outline seven teachings about human beings from the Biblical creation accounts.” “In both the husband & wife should give conjugal rights to each” (2020) was also an answer to the “state seven similarities between traditional African and Christian understanding of marriage.” However, there were some descriptions of inequality, such as “Christ is the head of the church just as the husband is the head of the wife” (2018). “The woman became subject to man/inferior” (2019) was also a model answer to “identify the consequences of sin from the story of the fall of human beings in Genesis chapter 3.” Furthermore, one answer to the question “unity of believers as expressed in the image of the bride” is “the committed Christian will be taken to a new home/heaven just as the bride is taken by her husband” (2019). In some cases, such as these, men and women do not seem to be seen as “equal.” The disunified attitude toward the value of gender equality is visible.

Critiques of homosexuality are distinctive. It was even described as “there is permissiveness in the society/moral decadence” (2020). Furthermore, to the question of “outline seven causes of homosexuality in Kenya today,” model answers include “peer pressure/bad company” and “due to Western influence” (2020). These expressions suggest that they reject the human rights of sexual minorities and attribute blame to Western influences.

This section can be summarized as follows. CRE critiques neoliberalism, condemning traits like greed and materialism. While poverty is acknowledged, voluntary wealth distribution is emphasized. The importance of sharing and helping others is recurrent, reflecting a communal perspective that contrasts with Western individualism. Regarding gender, CRE promotes equality but occasionally depicts women as subordinate, revealing a disunified stance on gender equality. Notably, CRE exhibits a distinct rejection of homosexuality, attributing its causes to peer pressure and Western influence.

These findings provide a nuanced understanding of equity-related discourse in Kenyan secondary education, with CRE playing a pivotal role in shaping moral perspectives. The study acknowledges the complexities within Kenyan society and highlights the need for a holistic examination of educational materials and official documents to comprehend the practical implications of equity concepts.

5. Discussion

5.1 The concept of “equity” and its coverage

According to UNESCO, “equity” in education denotes the fair and just extent to which children and adults have access to opportunities, striving to reduce disparities related to gender, poverty, residence, ethnicity, language, and other characteristics [25]. Confirming the occurrences of equity-related terms in the examined subjects aligns closely with UNESCO’s definition, emphasizing the necessity for equitable resource distribution irrespective of gender, race, or origin. However, the differential groups noted around the world were skewed in their concern for the issues, with a particular focus on issues that are particularly acute in the Kenyan context (e.g., race, gender, and ethnicity). In other words, it is influenced by the conditions and history of the country or society.

5.2 African curriculum’s “colonized” nature and distinctiveness in Kenya

Previous studies that have analyzed moral education that includes the concept of equity as it relates to justice and fairness have shown differences in the way it is accepted between Africa and the West, as indicated at the beginning of this chapter. This is explained by the historical background of the relationship between individuals and ethnic groups in Africa [5] and colonial policies [3]. Communalism in Africa, in contrast to Western individualism [4], shapes the concept of citizenship.

Additionally, moral education in Africa tends to draw value content exclusively from imported religions (e.g., Christianity and Islam) and excludes African-specific practices, cultures, experiences, challenges, and needs [4]. Therefore, studies on moral education have been criticized for the “colonization” of the African curriculum. However, it is also said that there is an uncritical assumption that what exists in Western countries is good for Africa [3]. Criticized for its “colonization” of the African curriculum, moral education could benefit from a more context-driven approach, incorporating indigenous knowledge [4].

In Kenya, despite practicing capitalism, the emphasis on communal redistribution is evident, differing from neighboring socialist models [26]. However, several concepts emblematic of the West (such as individualism, materialism, and the human rights of sexual minorities) were not acknowledged in the Kenyan examinations. Other subjects, such as HIS and BS, also strongly emphasize African socialism. From the analysis of examination papers, it appears that communal redistribution is preferable in Kenya. Stambach [27] also noted differences between Kenyan and Western attitudes toward Christianity. Stambach [27] states that America views Kenyans’ tendency to distribute funds to needy members from church resources as a form of mismanagement and even nepotism, but in Kenya, it is viewed as an expression of Christian concern and a form of service to the underprivileged.

The above shows that Kenyan notions of fairness and justice are not necessarily uncritical of those in the West but rather present values specific to Africa (e.g., communalism as in Nyayoism and Harambee) and a sense of justice at odds with the West (e.g., discourses that suggest gender inequality and negative views of sexual minorities). Moral education in Kenya, conducted within the Western-derived subject of CRE, tended to portray the African community positively, while some phenomena symbolic of the West were critically discussed. However, this does not necessarily imply only an antagonistic relationship between the West and Africa, as Bhola [6] claimed the importance of collaboration of indigenous and modern knowledge and ensure they be mutually enriching. Thus, when different values clash in a country or society, it is expected that they will influence each other and create other values. This will show the third way for the fusion and further development of a set of Western and African values, rather than the mere acceptance of Western copies in Africa or the perpetual confrontation between the West and Africa.

To add one last thing, as challenges of moral education through religious education, it can be noted that while acknowledging the diversity of religions, an emphasis on the primacy of Christianity was unavoidable. Some countries in Africa apply pluralist approaches to religious education but treat marginalized non-normative religions as add-on knowledge [3]. In Kenya, even Muslims are forced to choose CRE [23, 24]. This is a limitation faced by CRE, which is primarily responsible for moral education in Kenya.

5.3 Policy implication

To examine the policy and practice implications of the study, first, it is important to note that even if common international goals are established, their acceptance depends to a large extent on the historical and social context. In Kenya, ethnicity and gender were topics of particular interest, and there was a strong depiction of Africa against the West. This is not necessarily consistent with the “equity” contents envisioned by the common global goals.

Another characteristic of Kenya is the negative attitude toward economic differences itself and the emphasis on mutual assistance at the citizen level, as well as social security systems

The policy implication of these findings is that it is important to consider policy goals from a bottom-up perspective, seeking to understand how these values and goals are interpreted in Kenya, rather than from a top-down perspective, where Western-derived values and goals are applied to Kenyan policy.

6. Conclusion

The study aims to elucidate diverse perspectives on equity by analyzing humanities subjects in Kenyan secondary education. Results indicated positive assessments of equity and equality, coupled with negative evaluations of disparity and discrimination. Notably, while topics related to gender and ethnicity were relatively common, economic differences dominated discussions. Redress measures included a notable aversion to capitalism and individualism, alongside an emphasis on national and individual mutual assistance. This suggests that Kenya’s understanding of equity varies from Western perspectives, reflecting a unique moral standpoint.

However, the study’s reliance on exam questions and answers from the last 5 years imposes limitations. It is also hard to say that the arbitrariness of the author has been completely eliminated in the categorization of topics and the counting of frequently used terms. Further, while various expressions akin to equity were considered, such as equality, parity, fairness, and justice, the study could not fully capture how each term is defined and interpreted by the Kenyan government. Future research should extend beyond exam materials, encompassing official government documents and investigations into how these value concepts are taught in school settings for a more comprehensive understanding of equity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Osaka University and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20K13907. Yuki Miyamura, a graduate student at Osaka University, assisted in organizing the data. I would like to express my gratitude to all those involved.

References

- 1.

Espinoza O. Solving the equity-equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educational Research. 2007; 49 (4):343-363 - 2.

Gooden ST. From equality to social equity. In: Guy ME, Rubin MM, editors. Public Administration Evolving: From Foundations to the Future. New York: Routledge; 2015. pp. 211-230 - 3.

Matemba Y. Decolonizing religious education in sub-Saharan Africa through the prism of anticolonialism: A conceptual proposition. British Journal of Religious Education. 2021; 43 (1):33-45. DOI: 10.1080/01416200.2020.1816529 - 4.

Obiagu AN. Toward a decolonized moral education for social justice in Africa. Journal of Black Studies. 2023; 54 (3):236-263. DOI: 10.1177/00219347231157739 - 5.

Ekeh PP. Colonialism and the two publics in Africa: A theoretical statement. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 1975; 17 (1):91-112 - 6.

Bhola HS. Reclaiming old heritage for proclaiming future history: The knowledge-for development debate in African contexts. Africa Today. 2002; 49 (3):3-21 - 7.

Matemba YH. Continuity and change in the development of moral education in Botswana. Journal of Moral Education. 2010; 39 (3):329-343. DOI: 10.1080/03057240.2010.497613 - 8.

Barnes LP. What has morality to do with religious education? Journal of Beliefs & Values. 2011; 32 (2):131-141. DOI: 10.1080/13617672.2011.600813 - 9.

Genç M. Values education or religious education? An alternative view of religious education in the secular age, the case of Turkey. Education Sciences. 2018; 8 (4):220. DOI: 10.3390/educsci8040220 - 10.

Van Der Walt JL. Religion in education in South Africa: Was social justice served? South African Journal of Education. 2011; 31 (3):381-393. DOI: 10.15700/saje.v31n3a543 - 11.

Burchardt M. Transparent sexualities: Sexual openness, HIV disclosure and the governmentality of sexuality in South Africa. Culture, Health, & Sexuality. 2013; 15 (sup4):S495-S508. DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2012.744850 - 12.

North-West University, Potgieter FJ. Morality as the substructure of social justice: Religion in education as a case in point. South African Journal of Education. 2011; 31 (3):394-406. DOI: 10.15700/saje.v31n3a537 - 13.

Obidi SS. A study of the reactions of secondary grammar school students to indigenous moral values in Nigeria. Journal of Negro Education. 1993; 62 (1):82-90. DOI: 10.2307/2295401 - 14.

Enslin P. Citizenship education in post-apartheid South Africa. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2003; 33 (1):73-83 - 15.

Matereke KP. Whipping into line: The dual crisis of education and citizenship in postcolonial Zimbabwe. Educational Philosophy and Theory. 2012; 44 (S2):84-99. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00799.x - 16.

Wainaina PK, Arnot M, Chege F. Developing ethical and democratic citizens in a post-colonial context: Citizenship education in Kenya. Educational Research. 2011; 53 (2):179-192. DOI: 10.1080/00131881.2011.572366 - 17.

RoK [Republic of Kenya]. Economic Survey 2019. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2019 - 18.

Woolman DC. Educational reconstruction and postcolonial curriculum development: A comparative study of four African countries. International Education Journal. 2001; 2 (5):27-46 - 19.

Sakaguchi M, Ogawa M, Rasolonaivo AR, Sonoyama D. Exploring the concepts of ‘(In)equality’, ‘(In)equity’, and ‘(dis)parity’ in the National Curricula and Examinations of Secondary Education: A comparison between the cases of South Africa, Kenya, and Madagascar. Africa Educational Research Journal. 2021; 12 :49-62. DOI: 10.50919/africaeducation.12.0_49 - 20.

Manea AD. Influences of religious education on the formation moral consciousness of students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 149 :518-523. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.08.203 - 21.

Kowino OJ, Agak JO, Obiero-Owino CE. The perceived discrepancy between the teaching of Christian religious education and inculcation of moral values amongst secondary schools students in Kisumu East district. Kenya. Educational Research and Reviews. 2011; 6 (3):299-314 - 22.

Saoke VO, Ndwiga ZN, Githaiga PW, Musafiri CM. Determinants of awareness and implementation of five-stage lesson plan framework among Christian religious education teachers in Meru County, Kenya. Heliyon. 2022; 8 (11):e11177. DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11177 - 23.

Svensson J. Divisions, diversity, and educational directives: IRE teachers’ didactic choices in Kisumu, Kenya. British Journal of Religious Education. 2010; 32 (3):245-258. DOI: 10.1080/01416200.2010.498610 - 24.

Ali AA. Historical development of Muslim education in East Africa: An eye on Kenya. The Journal of Education in Muslim Societies. 2022; 4 (1):128-139. DOI: 10.2979/jems.4.1.08 - 25.

UNESCO. Education for all by 2015: Will we Make it? EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2008. Paris: UNESCO; 2008 - 26.

Oketch M, Rolleston C. Policies on free primary and secondary education in East Africa: Retrospect and prospect. Review of Research in Education. 2007; 31 (1):131-158 - 27.

Stambach A. Spiritual warfare 101: Preparing the student for Christian Battle. Journal of Religion in Africa. 2009; 39 (2):137-157. DOI: 10.1163/157006609X433358