Abstract

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the adult-elderly population is mostly arrhythmic due to acute thrombotic coronary artery occlusion or chronic ischemic heart disease. In the young atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) is thought to play a negligible role. We reviewed our pathology experience (1980–2016) in 690 consecutive SCDs in the young (≤40 years old, sudden infant death excluded). We found that CAD was the major cause of SCD (18%). It was observed in 125 subjects (mean age 32.3 ± 5.3 years, female 14), with a peak in 31–40 years old age interval. Site, extent, and histologic type of CAD were peculiar: single plaque of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, consisting of fibrocellular proliferation, with rare lipid core. The culprit atherosclerotic segment showed critical stenosis in 66% of cases and thrombotic occlusion in 34%, the latter as the consequence of plaque rupture in 47% and plaque erosion in 53%, which occurred even upon noncritical stenosis. An overt histologically acute myocardial infarction was never seen. When SCD took place during Holter monitory, transient myocardial ischemia was recorded, followed by ventricular fibrillation at the time of reperfusion. Atherosclerotic CAD was found to be the major cause of SCD also in the young, precipitated by acute coronary thrombosis in only a third of cases, more frequently upon endothelial erosion. Functional plaque instability with vasospasm, superimposed to a critical coronary plaque with ECG transient myocardial ischemia, was observed to precipitate SCD.

Keywords

- atherosclerosis

- coronary artery disease

- epidemiology

- prevention

- sudden death in the young

1. Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a fatal event, also occurring in the young. It may be due to structural heart disease or may occur in normal hearts in the setting of Channelopathies (“mors sine materia”) [1, 2]. While atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most frequent cause of SCD in the adult-elderly [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8], in the young it is considered a rare morbid entity, a belief that does not correspond to herein reported pathological experience.

2. Material and methods

In 1980 we implemented a prospective postmortem research project on sudden death in the young (age interval 2–40 years), studying all cases occurring in the Veneto Region, Italy. Most of the autopsies were carried out in peripheral hospitals.

Up to 2016, we studied 690 consecutive SCDs. The formalin-fixed heart specimens were forwarded to the Cardiovascular Pathology Unit of the University of Padua for examination, according to a thorough protocol [1, 9]. Molecular autopsy in apparently normal hearts was introduced in 2000 [10], and toxicology was performed when indicated [11]. After inspecting coronary ostia and excluding coronary artery anomalies, sections by the scalpel of the subepicardial coronary arteries were performed every 1–2 mm, and samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded for histology and immunohistochemistry.

3. Results

Sudden cardiac death was ascribed to atherosclerotic CAD in 125 out of 690 (18%) SCDs (mean age 32.3 ± 5.3, female 14). A single atherosclerotic plaque was found located in the proximal-middle tract of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LDA) in the great majority (95%).

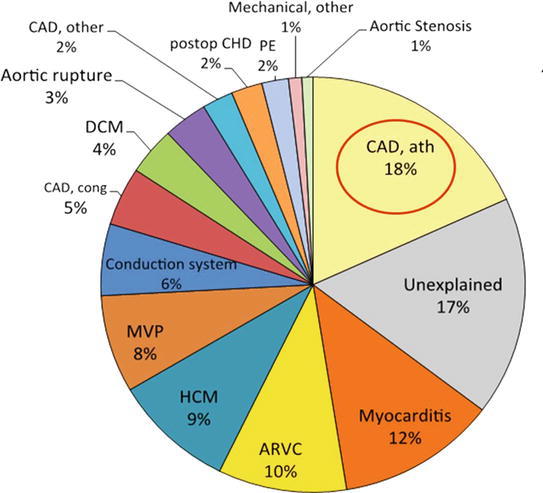

Figure 1 reports the various causes of SCD. Atherosclerotic CAD ranks first (18%), followed by “normal heart” (17%), myocarditis (12%), arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (10%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (9%) and mitral valve prolapse (8%).

Figure 1.

Causes of sudden cardiac death in 690 young subjects, Veneto region, Italy (1980–2016). Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) ranks first (18%). ARVC = Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; ath = atherosclerotic; CAD = coronary artery disease; cong = congenital; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; postop CHD = postoperative congenital heart disease.

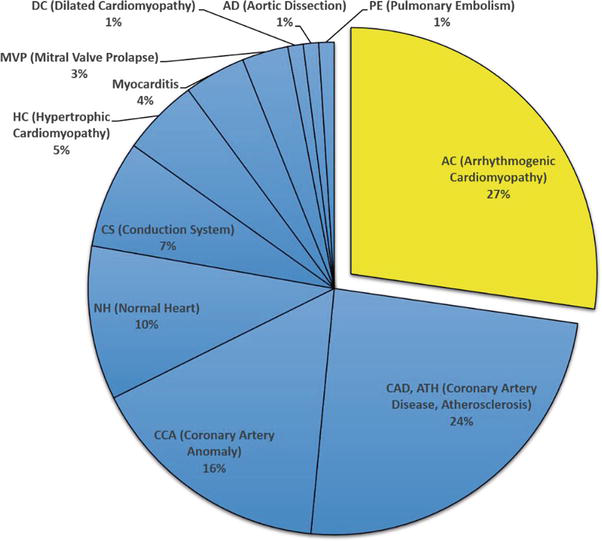

Figure 2 reports the various causes of SCD in 75 athletes, all male: arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy ranks first (27%), atherosclerotic CAD second (24%), and coronary artery anomalies third (17%).

Figure 2.

Sudden cardiac death in 75 athletes. Veneto region, Italy, 1980–2016. Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease ranks second (24%). AC = Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; AD = aortic dissection; CAD, ATH = coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis; CCA = coronary artery anomalies; CS = conduction system abnormalities; DC = dilated cardiomyopathy; HC = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; NH = Normal heart; PE = pulmonary embolism.

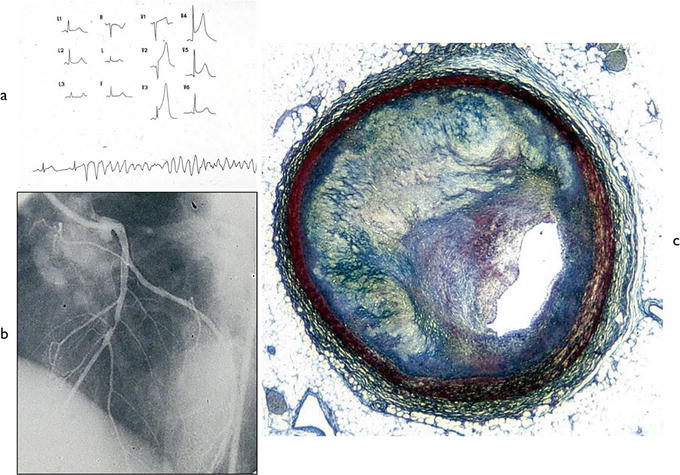

The culprit plaque in SCD by atherosclerotic CAD was either eccentric or concentric. In subjects aged less than 30 years, the plaques rarely disclosed a necrotic core (“atheroma”) and were mostly fibrous, with evidence of recent intimal proliferation on the lumen side (Figure 3). Critical stenosis (>75%), without evidence of fresh mural or occlusive thrombosis, was observed in 76 cases (61%). In two of the latter cases, SCD occurred during Holter monitoring, with evidence of transient ST-segment elevation, turning into ventricular fibrillation during reperfusion (Figure 3) [12].

Figure 3.

Vasospasm as a cause of SCD in a young. (a) ECG with transient ischemia turning into ventricular fibrillation; (b) selective coronary artery angiography: single eccentric obstructive plaque is located in the middle tract of the anterior descending coronary artery; (c) the corresponding histology of the plaque: Fibro cellular type without atheroma, with a recent intimal proliferation (Azan Mallory stain). From [

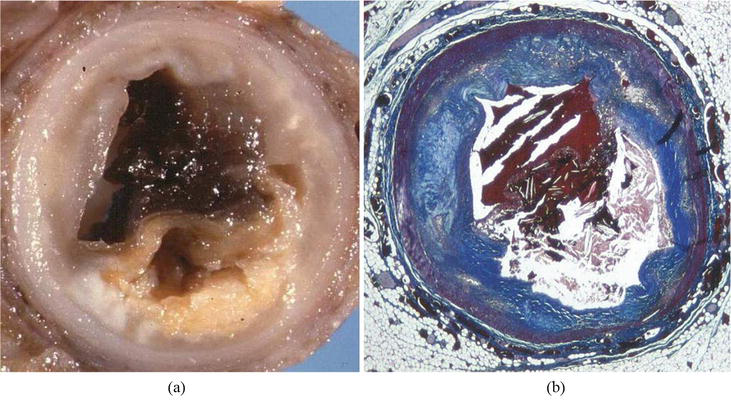

Thrombotic coronary artery occlusion was observed in 49 cases (39%). Plaque with fibrous cap rupture (Figure 4) accounted for thrombosis in 23 cases (47%, all >30 years old) and plaque erosion in 26 (53%) (Figure 5). The latter occurred upon noncritical plaque in 3 (Figure 6). Inflammatory infiltrates with endothelial disruption [13] accounted for erosion in three cases (Figure 7). Atherosclerotic plaques never exhibited calcification.

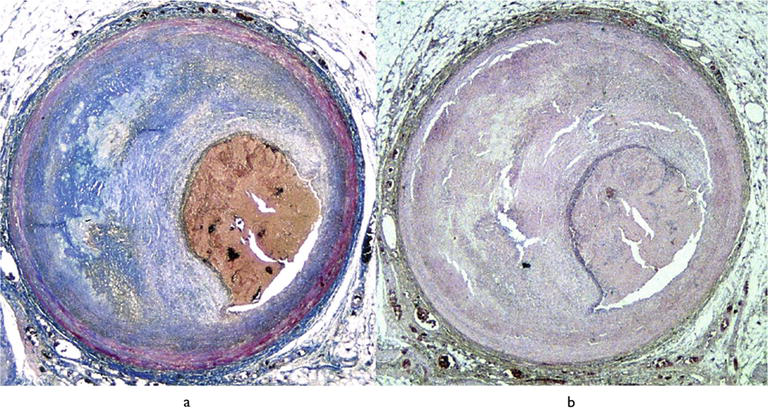

Figure 4.

Example of thrombotic occlusion by fibrous cap rupture. (a) Gross view; (b) corresponding histology. Note the disruption of the thin fibrous cap upon a large atheroma, including needles of cholesterol. Azan Mallory stain.

Figure 5.

Endothelial erosion, complicated by thrombotic occlusion of the lumen, in an eccentric atherosclerotic plaque of the anterior descending coronary artery, with critical stenosis. (a) Azan Mallory; (b) hematoxylin–eosin. Note the subendothelial inflammatory infiltrate covering the plaque, free from atheroma.

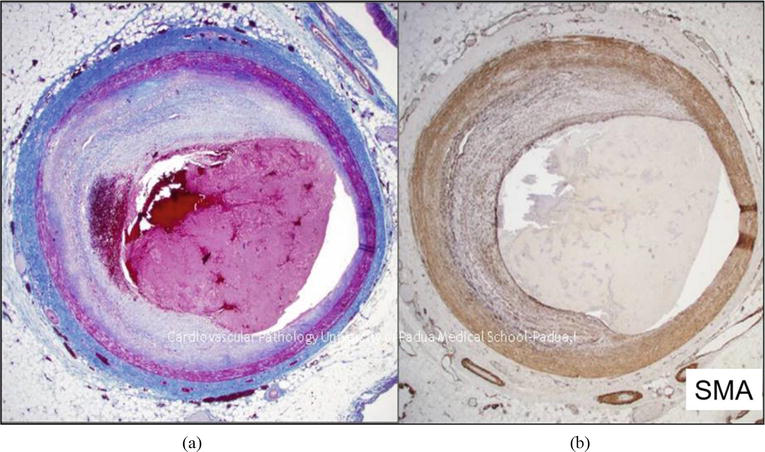

Figure 6.

Erosion occlusive thrombus upon a noncritical atherosclerotic plaque, free from atheroma. (a) Hematoxylin–eosin. (b) CD 38 immunostain.

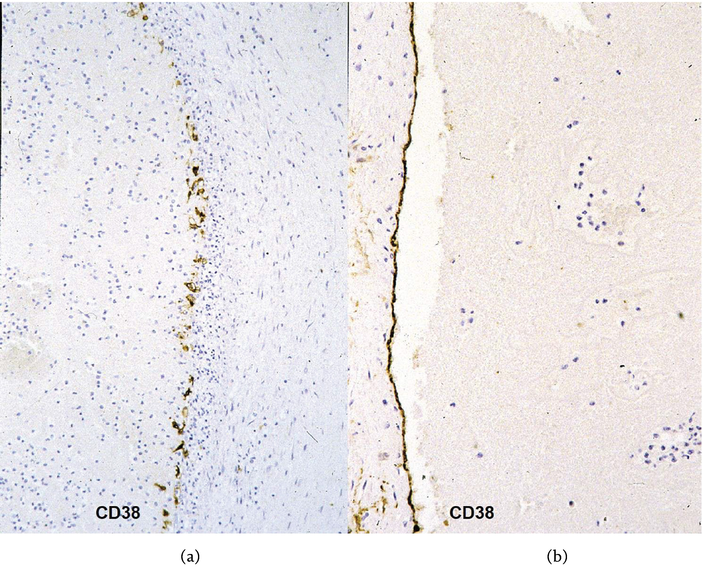

Figure 7.

Occlusive coronary thrombus by erosion. (a) Inflammatory disruption of the endothelial lining at the plant base of the thrombus; (b) intact endothelial lining of the opposite side. CD 38 immunostaining.

As far as the myocardium, histological evidence of an acute myocardial infarction was never observed, whereas fibrotic myocardial scars, in keeping with previous infarcts [1], were seen in 27% of SCD by atherosclerotic CAD.

4. Discussion

Our prospective investigation on SD in the young revealed that in the Veneto Region of Italy CAD is the major cause of SCD also in the young (2–40 years old).

CAD is a nightmare, confirming that atherosclerosis is an acquired “malignant” disease with the risk of premature SCD in the young [14]. The results of our investigation resemble an “Italian” paradox because the high rate of CAD in SCD of the young occurred in Italy, a country with a Mediterranean healthy diet.

Previous studies on the hearts of young people, who died of noncardiovascular disease, revealed that coronary atherosclerosis may appear under the age of 20 [15].

The atherosclerotic plaques of young subjects under 30 years old did not exhibit the classical characteristic of necrotic core and fibrous cap [9, 15]. They appeared fibrous, with recent intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation. Whether this is another type of arteriosclerosis or an early stage of plaque with atheroma remains elusive.

We had indeed the serendipity to study two cases who died suddenly during Holter monitoring after transient ST segment elevation [12]. A single coronary obstructive plaque was located at the proximal anterior descending coronary artery (called the coronary artery of sudden death by German pathologists). The plaque appeared either concentric or eccentric, without atheroma and fibrous cap. The ECG recorded anterior ST-segment elevation in keeping with transmural myocardial ischemia, which returned to normal in a few minutes, followed by the onset of ventricular fibrillation. Most likely, the malignant life-threatening electrical instability occurred during reperfusion at the time of spontaneous reopening of the coronary lumen. Unfortunately, the patients were alone, so resuscitation maneuvers could not be performed. At the microscope, the atherosclerotic plaques showed a recent intimal proliferation of smooth muscle cells (Figures 3 and 8). The tunica media appeared well preserved with normal thickness all around the coronary segment. Immunostaining demonstrated that intimal cell proliferation consisted of both synthetic and contractile smooth muscle cells, which most probably contributed to vasospasm [16]. There was no evidence of plaque rupture with platelets or fibrin adhesion. Thus cell proliferation was not consistent with plaque healing.

The origin of these subendocardial smooth muscle cells (Figure 8) is intriguing [17, 18, 19, 20]. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition has been postulated [21].

Figure 8.

A solitary plaque at the anterior descending coronary artery. (a) Panoramic view: Note the fibrocellular plaque. Azan Mallory stain; (b) close-up of the recent intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation. Hematoxylin–eosin stain.

Our findings suggest that plaque instability in the young is caused not only by plaque rupture or endothelial erosion with thrombosis but also by vasospasm of the culprit segment by intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation with contractile phenotype.

Coronary thrombosis in SCD of the young was mostly precipitated by endothelial erosion, with evidence of inflammatory disruption of the endothelium [13]. The cause of the latter is obscure. Moreover, thrombosis by erosion may occur even upon a noncritical plaque. It makes it impossible to detect by the stress test, which in Italy is mandatory for sports eligibility.

In conclusion, even in the young, atherosclerotic CAD is the main cause of SCD. Plaque instability may be either structural by thrombosis, mostly due to inflammatory erosion, or functional due to contractile intimal smooth muscle cell proliferation upon the plaque, accounting for transient coronary occlusion and acute myocardial ischemia, turning into ventricular fibrillation.

5. Limitation of the study

Data on risk factors, like smoking, cholesterol, hypertension, and familiarity, were unavailable since, in this young population, SCD occurred as a first manifestation of the disease in the absence of files from previous health visits.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Registry of Cardio-Cerebro-Vascular Pathology, Veneto Region, Venice, and by ARCA Foundation, Padua, Italy.

Acronyms and abbreviations

coronary artery disease electrocardiogram left anterior descending sudden cardiac death sudden death

References

- 1.

Thiene G, Corrado D, Basso C. Sudden Cardiac Death in the Young and Athletes. Text Atlas of Pathology and Clinical Correlates. Milan, Italy: Springer-Verlag; 2016. p. 190. ISBN 978-88-470-5775-3 - 2.

Thiene G. Sudden cardiac death and cardiovascular pathology: From anatomic theater to double helix. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014; 114 (12):1930-1936. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.037 - 3.

Lovegrove T, Thompson P. The role of acute myocardial infarction in sudden cardiac death – A statistician’s nightmare. American Heart Journal. 1978; 96 (6):711-713. DOI: 10.1016/0002-8703(78)90002-9 - 4.

Davies MJ. Stability and instability: Two faces of coronary atherosclerosis. The Paul Dudley White Lecture 1995. Circulation. 1996; 94 (8):2013-2020. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.2013 - 5.

Davies MJ. Anatomic features in victims of sudden coronary death. Coronary artery pathology. Circulation. 1992; 85 (1 Suppl):I19-I24 - 6.

Arbustini E, Grasso M, Diegoli M, Pucci A, Bramerio M, Ardissino D, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic plaques with and without thrombus in ischemic heart syndromes: A morphologic, immunohistochemical, and biochemical study. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1991; 68 (7):36B-50B. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90383-v - 7.

Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013; 368 (21):2004-2013. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1216063 - 8.

Crea F, Libby P. Acute coronary syndromes: The way forward from mechanisms to precision treatment. Circulation. 2017; 136 (12):1155-1166. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029870 - 9.

Corrado D, Basso C, Poletti A, Angelini A, Valente M, Thiene G. Sudden death in the young. Is acute coronary thrombosis the major precipitating factor? Circulation. 1994; 90 (5):2315-2323. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2315 - 10.

Basso C, Carturan E, Pilichou K, Rizzo S, Corrado D, Thiene G. Sudden cardiac death with normal heart: Molecular autopsy. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2010; 19 (6):321-325. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.02.003 - 11.

Montisci M, Thiene G, Ferrara SD, Basso C. Cannabis and cocaine: A lethal cocktail triggering coronary sudden death. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2008; 17 (5):344-346. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.05.005 - 12.

Corrado D, Thiene G, Buja GF, Pantaleoni A, Maiolino P. The relationship between growth of atherosclerotic plaques, variant angina and sudden death. International Journal of Cardiology. 1990; 26 (3):361-367. DOI: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90095-m - 13.

van der Wal AC, Becker AE, van der Loos CM, Das PK. Site of intimal rupture or erosion of thrombosed coronary atherosclerotic plaques is characterized by an inflammatory process irrespective of the dominant plaque morphology. Circulation. 1994; 89 (1):36-44. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.36 - 14.

Thiene G. More basic research on atherosclerosis to find targeted therapy and improve prevention. Circulation. 2013; 128 :f54. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a87d8aCirculation - 15.

Angelini A, Thiene G, Frescura C, Baroldi G. Coronary arterial wall and atherosclerosis in youth (1-20 years): A histologic study in a northern Italian population. International Journal of Cardiology. 1990; 28 (3):361-370. DOI: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90320-5 - 16.

Rizzo S, Coen M, Sakic A, De Gaspari M, Thiene G, Gabbiani G, et al. Sudden coronary death in the young: Evidence of contractile phenotype of smooth muscle cells in the culprit atherosclerotic plaque. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018; 264 :1-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.096 - 17.

Lambert J, Jørgensen HF. Vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching and plaque stability: A role for CHI3L1. Cardiovascular Research. 2021; 117 (14):2691-2693. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvab099 - 18.

Miano JM, Fisher EA, Majesky MW. Fate and state of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2021; 143 (21):2110-2116. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049922 - 19.

Tavora F, Cresswell N, Li L, Ripple M, Fowler D, Burke A. Sudden coronary death caused by pathologic intimal thickening without atheromatous plaque formation. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2011; 20 (1):51-57. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2009.08.004 - 20.

Horita A, Kurata A, Ohno S, Shimoyamada H, Saito I, Kamma H, et al. Immaturity of smooth muscle cells in the neointima is associated with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2015; 24 (1):26-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2014.09.003 - 21.

Jackson AO, Zhang J, Jiang Z, Yin K. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: A novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2017; 27 (6):383-393. DOI: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.03.003