Abstract

Rectal cancer patients with postoperative altered bowel function have poorer quality of life than colon rectal cancer patients with it. The altered bowel function symptoms were named low anterior resection syndrome. Mechanisms of these symptoms associated with removing rectum and receptors on its internal wall, creating neorectum, and destroying pelvic neuro-plexus by analsaving surgery. Due to the low anterior resection syndrome, patients suffered from physical, psychological and social impacts on quality of life. Three options are used to treat low anterior resection syndrome, including self-care strategies, clinician-initiated interventions, and creating a permanent stoma. The self-care strategies contain diet modification, lifestyle changes, and spiritual sublimation. The clinician-initiated interventions include prescribed medication, trans-anal irrigation, pelvic floor rehabilitation, neuromodulation, and so on. Creating a permanent stoma is the eventual choice due to anastomotic restriction. Altered bowel function may follow postoperative rectal cancer patients for whole life; however, flexibly using these care strategies may help them adjust.

Keywords

- colorectal cancer

- altered bowel function

- low anterior resection syndrome

- consequence of anal-saving surgery

- care strategies of low anterior resection syndrome

1. Introduction

Altered bowel function is a common consequence in postoperative colorectal cancer patients and may impact patients’ quality of life for years [1, 2, 3]. In the population, rectal cancer patients had worse long-term quality of life than colon cancer patients, which may relate to severer bowel dysfunction after they received anal-saving surgery [2, 4]. Improving the dysfunction in rectal cancer patients may effectively promote the quality of life in colorectal cancer patients [5]. The postoperative altered bowel function in rectal cancer patients with anal-saving surgery was named low anterior resection syndrome [6, 7]. This chapter will focus on definition of low anterior resection syndrome, the mechanisms of the dysfunction, its impactions on quality of life, and management strategies of low anterior resection.

2. Definition of low anterior resection syndrome

Under a consensus combined in the 17th European Colorectal Congress, low anterior resection syndrome was defined as a series of bowel dysfunction symptoms after patients received anal-saving surgery, such as anterior resection, low anterior resection, ultralow anterior resection, total mesorectal excision, and so forth [4, 6]. These symptoms and their incidence included small frequent stool (70–94.4%), altered anal sense (12–98%), fecal incontinence (12–97%), fecal urgency (67%), evacuator dysfunction (47%), varied stool forms (37.6%), and gas-stool discrimination (34%) [4, 6, 7, 8, 9]. These symptoms gradually spontaneously improved in the postoperative period but seldom totally recovered over years [4, 8, 9, 10, 11].

3. Mechanisms of low anterior resection syndrome

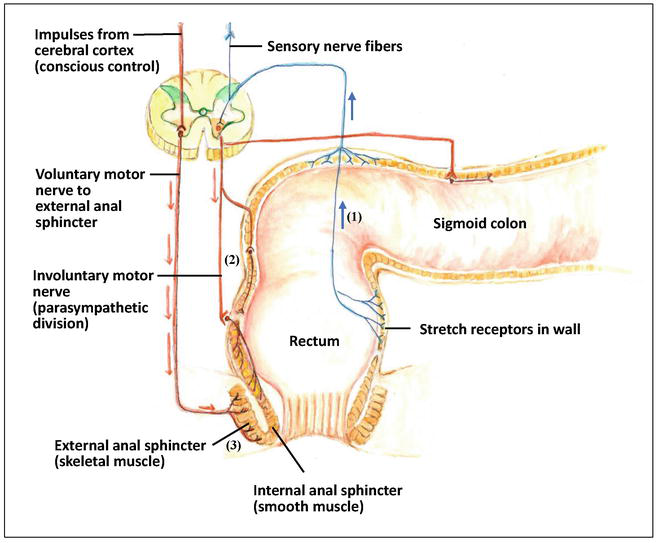

A mechanism of defecation includes a series of processes (see Figure 1): (1) When feces move into and distend the rectum, they stimulate stretch receptors in the wall of rectum, and the receptors transmit signals along afferent fibers to spinal cord neurons; (2) A spinal reflex is initiated in which parasympathetic motor fibers (efferent fibers) stimulate the contraction of the rectum and sigmoid colon and relaxation of the internal anal sphincter; (3) When it is convenient to defecate, voluntary motor neurons are inhibited, which allow the external anal sphincter to relax, and then feces may pass [12].

Figure 1.

The mechanism of defecation. (1) When feces move into and distend the rectum, they stimulate stretch receptors in the wall of rectum, and the receptors transmit signals along afferent fibers to spinal cord neurons, (2) A spinal reflex is initiated in which parasympathetic motor fibers (efferent fibers) stimulate the contraction of the rectum and sigmoid colon, and relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, (3) When it is convenient to defecate, voluntary motor neurons are inhibited, which allow the external anal sphincter to relax, and then feces may pass.

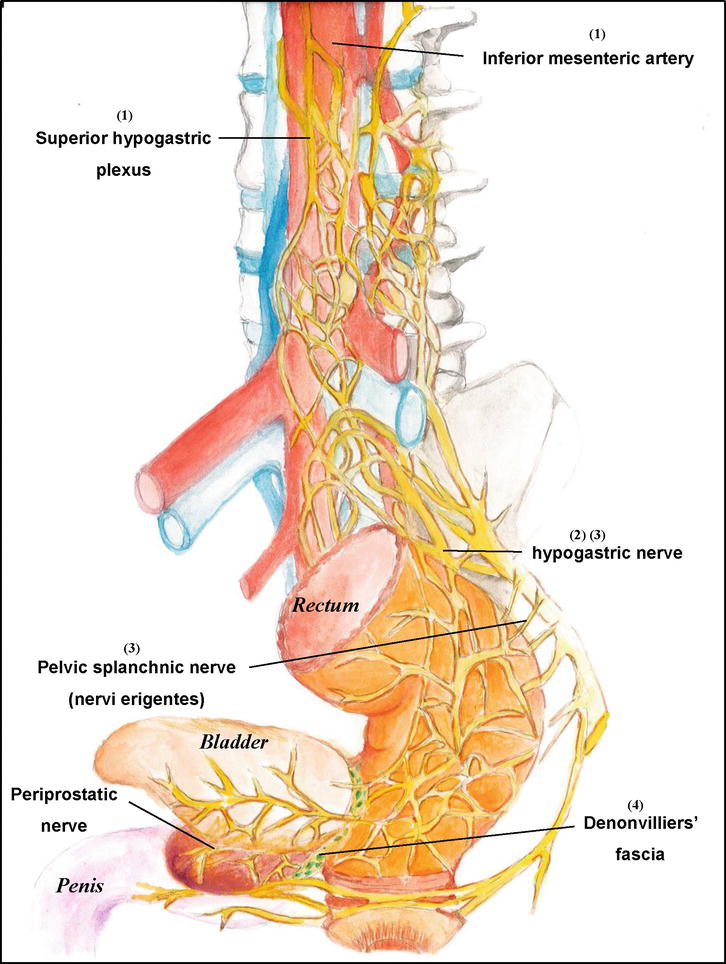

The purpose of anal-saving surgery is to save the anal sphincters and to avoid receiving abdominoperineal resection with permanent stoma [13]. When patients received anal-saving surgery, it may resect distal sigmoid, whole rectum, total mesorectum and partial or/and total internal sphincter or/and external sphincter, as well as straight down the stump of colon to create a colon-to-colon or coloanal anastomosis for bowel continuum [13, 14, 15]. Potential points of pelvic nerve injury during rectal dissection include (see Figure 2): (1) Damage to the superior hypogastric plexus from tension or high division of the inferior mesenteric artery, (2) Injury to the main trunks of the hypogastric nerve during retrorectal dissection; (3) Injury to the inferior hypogastric plexus and nervi erigentes during the mobilization of lateral stalks, and (4) injury to the periprostatic plexus during the dissection of Denonvilliers’ fascia [16, 17, 18].

Figure 2.

Potential points of pelvic nerve injury during rectal dissection include. (1) Damage to the superior hypogastric plexus from tension or high division of the inferior mesenteric artery. (2) Injury to the main trunks of the hypogastric nerve during retrorectal dissection. (3) Injury to the inferior hypogastric plexus and nervi erigentes during the mobilization of lateral stalks. (4) Injury to the periprostatic plexus during the dissection of Denonvilliers’ fascia.

When rectum was resected, the stump of colon was straightdown to form a neorectum [19]. Because of the neorectum with smaller volume and with decreasing available eastability following chemoradiotherapy, the mechanic change may induce small frequent stool and varied stool forms; smaller volume of neorectum and resection of the stretch receptors in the wall of rectum may lead to fecal urgency, evacuator dysfunction, altered anal sense, and gas-stool discrimination; resection of rectal receptors, destroying of pelvic neuro-plexus and resection of anal sphincter may cause fecal incontinence [13, 15, 19].

4. The symptom distress and impactions on quality of life related to low anterior resection syndrome

After rectal cancer patients received anal-saving surgery or reversal of temporary stoma, they experienced varied symptoms of altered bowl function [20, 21, 22]. They were often preoccupied with these uncontrolled excrement symptoms, which easily disturb their physical function, compel them to experience emotional distress, and interfere with their social activities [7, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. Additionally, a multicenter correctional study revealed patients with the major low anterior resection syndrome had significantly worse quality of life than the those with minor and moderate syndrome [25].

In the domain of physical function, interruption of daily activities (e.g., eating, householding, and sleep), consequent distraction in daytime, and decreased sexual behavior often related to small frequent defection, urgency, and fecal incontinence [20, 22]. Under the disturbance of sleep, there may be difficulty in falling asleep, interruption of sleep due to intent to defecate, difficulty in falling asleep post broken sleep at midnight, and poor quality of sleep [7, 20]. On the intimacy behaviors, patients and their couples may choose other methods (e.g. hug, kiss, and spiritual empathy, etc.) to replace sexual behaviors [7].

In the domain of psychological function, patients often develop varied negative moods due to uncontrolled excrement, such as distress, depress, upset, botheration, irritation, helplessness, loneness, hopelessness, and so on [7, 20, 23]. They feel tie to toilet due to frequent go to restroom, experience struggle in living because of relieving from stoma but falling in destructive bowel habits, though it is a price to survive from cancer, and mark stigma related to uncontrolled incontinence [20, 26, 27]. They often fear the spread of poor odor and feel embarrassment due to fecal incontinence [27], which lead to concern over the availability of restroom [7].

In the domain of social function, patients do not dare to go outside or dinning, compete to go to restroom with family members, are forced to change mode of work, decrease travel, and give up enjoyment [7, 20]. Their lifestyle changes may bother their family, and they may suffer from loneness because their family cannot totally understand their feeling [7, 23]. Their life style changed, thus, they feel they become a different person, in the other ward, their body image was changed [7, 26, 28]. At the same time, they also suffered from social isolation [20, 21, 26].

5. The management strategies of low anterior resection syndrome

Although management of low anterior resection syndrome remains equivocal, some strategies are mentioned [5, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. The strategies involve in three options: self-care strategies, clinician-initiated interventions, and creating a permanent stoma [29, 30, 31, 35].

5.1 Self-care strategies

The self-care strategies for treating low anterior resection syndrome contain diet modification, lifestyle changes, and spiritual sublimation [29].

Diet modification is the commonest strategy to treat the altered bowel function in postoperative rectal cancer patients [32]. Some types of foods leading to aggravation of bowel dysfunction were advised, including greasy foods, liquid foods, gas-inducing foods, sweet foods, and stimulating foods [32, 33, 36]. These foods easily increase the frequency of defecation and possibly induce diarrhea, urgency, fecal incontinence, or/and gas-stool discrimination [32]. Notably, the mechanism may be supported by a correlative study, which revealed some nutrients aggravate bowel dysfunction; for example, the consumption of protein, cholesterol, and fruit increases the frequency and urgency of defecation; the consumption of fruit decreases the abnormal sense of defecation, but the interaction of wheats and milk leads to an abnormal sense of defecation [37]. The consumption of high-fiber foods remained equivocal; some studies mentioned that it may increase the risk of diarrhea and frequency of bowel movement, but it also may decrease the incidence of fecal incontinence when taken an amount of 25 g in a day [31, 32, 33]. Although patients’ motivation of diet modification is usually driven by burden of low anterior resection syndrome, they often have a trial-and-error process, need to overcome general habits, and face social interfering factors before forming new eating habits, such the availability of diet preparation, the time and amount of eating regularly, and so on [38].

Lifestyle change is a consequence of suffering from low anterior resection syndrome and also is a strategy of treating it [32, 39]. To have a supply of anal skin-care products and use sitz bath can decease perianal soreness related to frequent defecation [29]. When patients go outside, using wipes or pads, carrying spare clothes, and confirming the availability of restroom can help them to manage the embarrassment related to fecal incontinence [7, 29]. Participating some activities to divert patients’ attention from defecation is a useful method to control bowel symptoms, such as walking, jogging, going work, joining religion ceremony, and so on [33, 40]. Minor patients note that special body position can improve evacuator function; additionally, some patients change their schedule or mode of jobs for return-to-work [33].

In spiritual sublimation, building up a confidence of managing low anterior resection and feeling normality, constructing positive or thankful life attitude, accepting the dysfunction as part of them, and seeking reason to be strong usually help patients to adjust their altered bowel function and cancer disease [7, 23, 33]. In clinical practice, healthcare professionals can find that symptoms did not disappear, but positive attitude and thinking can promote patients’ perception and quality of life [7, 24]. Acceptability and sharing experiences with other rectal cancer patients with low anterior resection syndrome can decrease patients’ loneness and helplessness [23, 24].

5.2 Clinician-initiated interventions

The clinician-initiated interventions for managing low anterior resection syndrome include prescribed medication, trans-anal irrigation, pelvic floor rehabilitation (such as pelvis floor exercise, biofeedback, functional electrostimulation, and rectal balloon training), and neuromodulation (percutaneous/transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and sacral nerve stimulation), and so forth [29, 41].

Some prescribed medications are usually used to improve these altered bowel function [29, 32]. Phenylephrine gel twice a day or once every 8 hours may increase the anal sphincter resting pressure and decrease fecal incontinence, and Botox-A may relieve anal neuropathic pain [26, 38]. Loperamide is the most commonly prescribed oral anti-diarrhea agent to treat low anterior resection syndrome, which can activate the resting tone of internal anal sphincter and reduce episodes of defecation [31]. In clinical practice, the dose of anti-diarrhea medicine is often used by patients’ self-judgment [32].

Indication of trans-anal irrigation is suggested for use in postoperative rectal cancer patients with severe or chronic low anterior resection syndrome [31]. The procedure of irrigation is usually undertaken with a rectal catheter or an anal cone and using 500 to 1500 mL daily or three to four time a week; patients usually train by clinicians or using a training video, and then they are also supervised the outcomes at least 4 weeks to 6 months [29]. The volume of irrigation, intervals between irrigation procedure, and choice of irrigation device remained equivocal and depend on patients’ or educators’ judgment [31, 39]. Under patients’ perception, trans-anal irrigation can improve symptoms of low anterior resection, control the time of defecation, and promote their quality of life; however, patients may feel stressful and have intent of refusal due to conduct the procedure with catheterization [39].

The mechanism of pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation focuses on training coordination, sensory function, and strength of pelvis floor muscle to improve fecal incontinence [31]. The methods may consist of: (1) Pelvis floor muscle training depends on steady contraction of pelvis floor muscles to increase maximum strength, extend the duration of contractions, and improve coordination of pelvic floor muscles (a recommended frequency of the contraction is 25-40 times for three sections a day); (2) Biofeedback allows patients to directly visualize the effects of contraction and relaxation of the pelvis floor muscle and helps them to maintain habitually high-quality pelvic floor movement; (3) Functional electrostimulation induces construction of pelvis floor, and then, patients relearn and optimize the contractions by sensory feedback of this artificial contraction; and (4) Rectal balloon training depends on putting a balloon into rectum to stimulate intent of defecation, and then, patients are trained to resist the urge to defecate [29, 30, 42, 43, 44]. Varied studies validate the effectiveness of the contents of intervention, which include pelvis floor muscle training alone, biofeedback with pelvis floor muscle training, electromyography biofeedback, rectal balloon biofeedback, or all of them [45]. Although the better benefits seem to be proved on multimodalities than the single one, but the conclusion remained equivocal because of several risks of bias, including low quality across all studies due to small sample sizes, insufficient long-term follow-up, lack of randomized and blinding assessment, and heterogeneity of outcome [31, 45]. Additionally, patients’ satisfaction remained unclear [46].

Neuromodulation included percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, and sacral nerve stimulation, which can restore neural pathway by continuous neural stimulation to treating various forms of urinary and fecal incontinence by activating nerve potentials to contract anal sphincter [31]. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is applying a needle electrical stimulation into the tibial nerve at ankle, and is undertaking for 12, 17, or 20 sessions each lasting for 30 minutes; the undertaken intervals are more frequently initially, either once or twice a week, decreasing to weekly, fortnightly, monthly or sixmonthly [29]. The transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is to undertake a similar method of transcutaneous one, but it is using a cutaneous pad to substitute the needle electrical stimulation [31]. The procedure of sacral nerve stimulation is to put a lead of temporary external stimulator at the level of S2, S3, or S4 under general anesthesia, connecting it to a sacral nerve stimulation device and fixing its positions in a subcutaneous gluteal pocket; the setting divides the test and permanent stage, and the permanent implementation is conducted after confirming effective response during test stage [47]. The benefits of neuromodulation were revealed in previous studies, however, they still remained biases due to the results from researches with small sample sizes and lack of long-term follow-up [29, 31].

5.3 Creating a permanent stoma

Anastomosis stricture may develop in postoperative rectal cancer survivor, which may relate to previous radiation and surgery and aggravate symptoms of altered bowel function [30, 35]. When reconstruction of anastomosis is a contraindication to patients, creating a permanent stoma should be the eventual choice [30].

6. Conclusion

Altered bowel function is a consequence of anal-saving surgery. The symptoms impact patients’ physical, psychological, and social domains of quality of life and may follow postoperative rectal cancer patients for whole life. Flexibly using these care strategies may help them rebalance on a new road.

Acknowledgments

I am sincerely thankful for the all kind help from our editing team and the opportunity to share knowledge. The figures in this chapter were created by Li-Hua Fang, a pharmacist from the Department of Pharmacy at the Koo-Foundation Sun Yet-Sen Cancer Centre in Taipei, Taiwan.

References

- 1.

Korai T, Akizuki E, Okita K, Nishidate T, Okuya K, Sato Y, et al. Defecation disorder and anal function after surgery for lower rectal cancer in elderly patients. Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 2021; 6 (1):101-108 - 2.

Jansen L, Herrmann A, Stegmaier C, Singer S, Brenner H, Arndt V. Health-related quality of life during the 10 years after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A population-based study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011; 29 (24):3263-3269 - 3.

Su J, Liu Q , Zhou D, Yang X, Jia G, Huang L, et al. The status of low anterior resection syndrome: Data from a single-center in China. BMC Surgery. 2023; 23 (1):1-9 - 4.

Knowles G, Haigh R, McLean C, Phillips HA, Dunlop MG, Din FV. Long term effect of surgery and radiotherapy for colorectal cancer on defecatory function and quality of life. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013; 17 (5):570-577 - 5.

Laursen BS, Sørensen GK, Majgaard M, Jensen LB, Jacobsen KI, Kjær DK, et al. Coping strategies and considerations regarding low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life among patients with rectal cancer; a qualitative interview study. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022; 12 :1040462 - 6.

Keane C, Wells C, O'Grady G, Bissett IP. Defining low anterior resection syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. Colorectal Disease: the Official Journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2017; 19 (8):713-722 - 7.

Lu LC, Huang XY, Chen CC. The lived experiences of patients with post-operative rectal cancer who suffer from altered bowel function: A phenomenological study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2017; 31 :69-76 - 8.

Maris A, Penninckx F, Devreese AM, Staes F, Moons P, Van Cutsem E, et al. Persisting anorectal dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 (11):e672-e679 - 9.

Chatwin NAM, Ribordy M, Givel JC. Clinical outcomes and quality of life after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. The European Journal of Surgery - Acta chirurgica. 2002; 168 (5):297-301 - 10.

Li C, Tang H, Zhang Y, Zhang Q , Yang W, Yu H, et al. Experiences of bowel symptoms in patients with rectal cancer after sphincter-preserving surgery: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2022; 31 (1):23 - 11.

Varghese C, Wells CI, O'Grady G, Christensen P, Bissett IP, Keane C. The longitudinal course of low anterior resection syndrome: An individual patient meta-analysis. Annals of Surgery. 2022; 276 (1):46-54 - 12.

Martin F, Nath J, Bartholomew E. Fundamentals of Anatomy & Physiology. 12th ed. Pearson; 2023 - 13.

Pucciani F. A review on functional results of sphincter-saving surgery for rectal cancer: The anterior resection syndrome. Updates in Surgery. 2013; 65 (4):257-263 - 14.

Barisic G, Markovic V, Popovic M, Dimitrijevic I, Gavrilovic P, Krivokapic Z. Function after intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer and its influence on quality of life. Colorectal Disease. 2011; 13 (6):638-643 - 15.

Wallace MH. Glynne-Jones R: Saving the sphincter in rectal cancer: Are we prepared to change practice? Colorectal Disease. 2007; 9 (4):302-308; discussion 308-309 - 16.

Chew MH, Yeh YT, Lim E, Seow-Choen F. Pelvic autonomic nerve preservation in radical rectal cancer surgery: Changes in the past 3 decades. Gastroenterology Report (Oxford). 2016; 4 (3):173-185 - 17.

Sanghyun A, Ik Yong K. Pelvic anatomy for distal rectal cancer surgery. In: John C-B, editor. Current Topics in Colorectal Surgery. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2021. Ch. 7 - 18.

Varghese C, Wells CI, Bissett IP, O'Grady G, Keane C. The role of colonic motility in low anterior resection syndrome. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022; 12 :975386 - 19.

Chen SC, Futaba K, Leung WW, Wong C, Mak T, Ng S, et al. Functional anorectal studies in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2022; 34 (3):1-10 - 20.

Taylor C, Bradshaw E. Tied to the toilet: Lived experiences of altered bowel function (anterior resection syndrome) after temporary stoma reversal. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2013; 40 (4):415-421 - 21.

Reinwalds M, Blixter A, Carlsson E. A descriptive, qualitative study to assess patient experiences following stoma reversal after rectal cancer surgery. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2017; 63 (12):29-37 - 22.

Tsui H, Huang XY. Experiences of losing bowel control after lower anterior resection with sphincter saving surgery for rectal cancer: A qualitative study. Cancer Nursing. 2022; 45 (6):E890-E896 - 23.

Pape E, Decoene E, Debrauwere M, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Pattyn P, Feryn T, et al. The trajectory of hope and loneliness in rectal cancer survivors with major low anterior resection syndrome: A qualitative study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2022; 56 :102088 - 24.

Buergi C. It has become a part of me: Living with low anterior resection syndrome after ostomy reversal: A phenomenological study. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2022; 49 (6):545-550 - 25.

Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: An international multicenter study. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2014; 57 (5):585-591 - 26.

Reinwalds M, Blixter A, Carlsson E. Living with a resected rectum after rectal cancer surgery-struggling not to let bowel function control life. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018; 27 (3-4):e623-e634 - 27.

Desnoo L, Faithfull S. A qualitative study of anterior resection syndrome: the experiences of cancer survivors who have undergone resection surgery. European Journal of Cancer Care (England). 2006; 15 (3):244-251 - 28.

Hirpara DH, Azin A, Mulcahy V, Le Souder E, O’Brien C, Chadi SA, et al. The impact of surgical modality on self-reported body image, quality of life and survivorship after anterior resection for colorectal cancer – A mixed methods study. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2019; 62 (4):235-242 - 29.

Burch J, Swatton A, Taylor C, Wilson A, Norton C. Managing bowel symptoms after sphincter-saving rectal cancer surgery: A scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021; 62 (6):1295-1307 - 30.

Sarcher T, Dupont B, Alves A, Menahem B. Anterior resection syndrome: What should we tell practitioners and patients in 2018? Journal of Visceral Surgery. 2018; 155 (5):383-391 - 31.

Rosen H, Sebesta CG, Sebesta C. Management of low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) following resection for rectal cancer. Cancers. 2023; 15 (3):778 - 32.

Yin L, Fan L, Tan R, Yang G, Jiang F, Zhang C, et al. Bowel symptoms and self-care strategies of survivors in the process of restoration after low anterior resection of rectal cancer. BMC Surgery. 2018; 18 (1):35 - 33.

Liu W, Xia HO. Can I control my bowel symptoms myself? The experience of controlling defaecation dysfunction among patients with rectal cancer after sphincter-saving surgery: A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health & Well-Being. 2022; 17 (1):1-13 - 34.

Pape E, Van Haver D, Lievrouw A, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Van De Putte D, Van Ongeval J, et al. Interprofessional perspectives on care for patients with low anterior resection syndrome: A qualitative study. Colorectal Disease. 2022; 24 (9):1032-1039 - 35.

Zeman M, Czarnecki M, Chmielarz A, Idasiak A, Grajek M, Czarniecka A. Assessment of the risk of permanent stoma after low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2020; 18 (1):207 - 36.

Harji D, Fernandez B, Boissieras L, Berger A, Capdepont M, Zerbib F, et al. A novel bowel rehabilitation programme after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: The BOREAL pilot study. Colorectal Disease. 2021; 23 (10):2619-2626 - 37.

Liu W, Xu JM, Zhang YX, Lu HJ, Xia HO. The relationship between food consumption and bowel symptoms among patients with rectal cancer after sphincter-saving surgery. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021; 8 :642574 - 38.

Liu W, Xu JM, Zhang YX, Lu HJ, Xia HO. The experience of dealing with defecation dysfunction by changing the eating behaviours of people with rectal cancer following sphincter-saving surgery: A qualitative study. Nursing Open. 2021; 8 (3):1501-1509 - 39.

McCutchan GM, Hughes D, Davies Z, Torkington J, Morris C, Cornish JA. Acceptability and benefit of rectal irrigation in patients with low anterior resection syndrome: A qualitative study. Colorectal Disease. 2017; 20 :O76-O84 - 40.

Nakagawa H, Sasai H, Tanaka K. Defecation dysfunction and exercise habits among survivors of rectal cancer: A pilot qualitative study. Healthcare (Basel). 2022; 10 (10):2029 - 41.

Rodrigues BDS, Rodrigues FP, Buzatti KCLR, Campanati RG, Profeta da Luz MM, Gomes da Silva R, et al. Feasibility study of transanal irrigation using a colostomy irrigation system in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2022; 65 (3):413-420 - 42.

van der Heijden JAG, Kalkdijk-Dijkstra AJ, Pierie JPEN, van Westreenen HL, Broens PMA, Klarenbeek BR. Pelvic floor rehabilitation after rectal cancer surgery. A Multicenter randomized clinical trial (FORCE trial). Annals of Surgery. 2022; 276 (1):38-45 - 43.

Sacomori C, Lorca LA, Martinez-Mardones M, Salas-Ocaranza RI, Reyes-Reyes GP, Pizarro-Hinojosa MN, et al. A randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of pre- and post-surgical pelvic floor physiotherapy for bowel symptoms, pelvic floor function, and quality of life of patients with rectal cancer: CARRET protocol. Trials. 2021; 22 (1):1-11 - 44.

Asnong A, D'Hoore A, Van Kampen M, Wolthuis A, Van Molhem Y, Van Geluwe B, et al. The role of pelvic floor muscle training on low anterior resection syndrome: A Multicenter randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery. 2022; 276 (5):761-768 - 45.

Chan KYC, Suen M, Coulson S, Vardy JL. Efficacy of pelvic floor rehabilitation for bowel dysfunction after anterior resection for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021; 29 (4):1795-1809 - 46.

Li H, Guo C, Gao J, Yao H. Effectiveness of biofeedback therapy in patients with bowel dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery: A systemic review with meta-analysis. Therapeutics & Clinical Risk Management. 2022; 18 :71-93 - 47.

De Meyere C, Nuytens F, Parmentier I, D'Hondt M. Five-year single center experience of sacral neuromodulation for isolated fecal incontinence or fecal incontinence combined with low anterior resection syndrome. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2020; 24 (9):947-958