Oxford classification of the rectal prolapses.

Abstract

Rectal prolapse is a debilitating medical condition known to significantly compromise an individual’s quality of life. Optimal management typically entails trans-abdominal minimally invasive surgical interventions, particularly when performed with stringent adherence to appropriate indications. Such surgical interventions hold the potential to ameliorate patients’ symptoms and enhance their overall quality of life. A prerequisite for the successful execution of these surgical procedures is a comprehensive preoperative assessment, encompassing a thorough analysis of rectal and anal functionality. This essential evaluation serves as a crucial determinant in achieving optimal surgical outcomes. Moreover, due to the frequent concurrence of anterior prolapse with urinary and gynaecologic dysfunctions, a multidisciplinary assessment becomes imperative. A multidisciplinary discussion involving various medical specialties is pivotal in guiding treatment decisions. In conclusion, a meticulous preoperative assessment is paramount in selecting the most suitable surgical approach, thereby facilitating an enhancement in the patient’s quality of life.

Keywords

- rectal prolapse

- rectocele

- ventral rectopexy

- perineal surgical approach

- complication rate

1. Introduction

Rectal prolapse denotes a pathological condition characterised by the complete or partial invagination of the upper rectum [1]. This phenomenon manifests in two distinct forms: internal and external (Figure 1), with the latter being discernible upon perianal examination if reduction cannot be achieved. Following a Valsalva manoeuvre, rectal prolapse may either spontaneously resolve or necessitate manual reduction via digital pressure. In select instances, it may prove non-reducible, thereby inducing symptoms such as pain, ulceration, haemorrhaging, incarceration, and gangrene (Figure 2). In such cases, rectal prolapse constitutes a formal surgical indication requiring immediate attention [2]. This surgical intervention typically entails resection and the creation of a stoma.

Figure 1.

External rectal prolapse.

Figure 2.

Complicated large external recto-sigmoid prolapse with mucosal ischemia.

The incidence rate of rectal prolapse is reported as 2.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, with a notably higher prevalence among elderly women, demonstrating a gender ratio of 9:1 [1, 3]. In a recent work published by El-Dhuwaib et al. [4] including one of the largest databases concerning this pathology including more than 25,000 patients treated between 2001 and 2012, a higher incidence was found that rose to 18.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. Frequently, this condition is observed in patients with a medical history characterised by chronic constipation, strenuous defecation, pelvic floor dysfunction, or perineal obstetric injuries [1, 2]. Despite ongoing research efforts, the precise pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning rectal prolapse remain inadequately understood [5]. There exists some systemic pathology like the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and the mucoviscidosis or cystic fibrosis that are found to be risk factors for the development of the rectal prolapse. In a paper published by Joshi et al. [6] they found an increased quantity of elastic fibres in patients with rectal prolapse compared to the control population.

Another recent paper published by Attaallah et al. [7] demonstrate a possible role of the rectal redundancy in the physiopathology of the rectal prolapse.

Patients with rectal prolapse commonly exhibit various anatomical anomalies, including a rectum with a straight alignment, absence of fascial attachments between the rectum and the sacrum, redundancy of the sigmoid colon, diastasis of the levator ani muscles, abnormal deep Douglas pouch, and a patulous anus [2].

These patients are characterised by a medical history that often includes symptoms such as incontinence and constipation. In cases where external full-thickness prolapse is present, patients may experience passive incontinence, urge incontinence, or soiling as additional symptoms [2].

Constipation is used to describe symptoms that relate to difficulties in defecation; this includes infrequent bowel movements, hard or lumpy stools, excessive staining, a sensation of incomplete evacuation of blockage, and, in some cases, the use of manual manoeuvres to facilitate evacuation. The chronic constipation affects around 10–15% of the population and is one of the prevalent gastroenterological entities. Following the Rome IV criteria, constipation is categorised into four different subtypes [8]:

Functional constipation

Irritable bowel syndrome avec constipation

Opioid-induced constipation

Functional defecation disorders, including inadequate defecatory propulsion and dyssynergic defecation.

Obstructive defecation syndrome (ODS) is a functional defecation disorder characterised by excessive staining, the sensation of incomplete evacuation, the sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, and/or manual assistance to facilitate the evacuation in more than 25% of bowel movements over the last 12 consecutive weeks [9]. From an anatomical perspective, ODS is primarily associated with specific anatomical factors, namely rectocele, internal rectal prolapse, and enterocele.

Rectocele is characterised by the protrusion of the rectum into the vaginal cavity. This occurrence results from damage to the posterior compartment, leading to the weakening of the posterior vaginal wall support [10], or it can involve the herniation of the anterior rectal wall into the posterior vagina [11]. Enterocele, on the other hand, entails the compression of the small intestine against the rectal wall, typically occurring in patients with an abnormal deep Douglas pouch. Enterocele is a type of elitrocele [12], which is defined as a herniation of the Douglas pouch which is interposed between the vagina and the rectum. Based on the content of this deep Douglas pouch, we should talk about:

Enterocele: the presence of a small bowel in the deep part of the Douglas pouch hernia

Sigmoidocele: the presence of a sigmoid colon, usually in the case of a dolico-sigmoid

Epiplooncele: the presence of epiploon in the deepest part of the Douglas cavity

It is worth noting that internal rectal prolapse and rectocele frequently coexist.

Rectocele is diagnosed in more than half of women presenting with pelvic floor disorders [10], although its true incidence and pathogenesis remain subject to controversy [11]. In approximately 80% of cases, rectocele coexists with an internal rectal prolapse, whereas isolated rectocele is found in only 10% of cases [13]. Surgical intervention is recommended when rectocele is symptomatic; however, if a non-symptomatic rectocele is discovered, surgical intervention is not advised. The primary objective of surgical treatment for this type of functional pathological finding is symptom resolution [10].

Some authors have identified significant correlations between pelvic floor disorders and certain factors, including a younger age at first delivery, a higher body mass index, forceps delivery, and a history of previous gynaecologic surgery [2, 10].

On occasion, rectifying the underlying anatomical disorder may not necessarily correspond to an amelioration of symptoms. This observation raises the possibility of a common tendency to underestimate other potential contributing factors in this intricate syndrome [14]. Such factors can exert a significant influence on individuals’ quality of life and carry substantial social and economic implications, particularly within the context of an ageing population [15]. It’s so important in this type of situation to tailor the preoperative management and the surgical indication based on the individual patient’s characteristics.

2. Clinical findings and diagnosis

Patients with rectal prolapse typically present with several common complaints, including the sensation of a protruding mass following defecation or the need to manually reduce this protrusion [1]. Additionally, they may experience mucous discharge during defecation, and in some cases, bleeding can occur due to a solitary ulcer. In elderly patients, incontinence can be reported in up to 88% of cases, while constipation may affect as many as 70% of individuals with rectal prolapse [1].

The preoperative assessment of symptom severity holds paramount importance [3]. It enables a more objective evaluation of the post-operative course and facilitates the assessment of functional outcomes during follow-up. Various scoring systems are available for this purpose, such as the Wexner, FISI, GIQL (general Quality of Life), and Vaizey scores.

Clinical examination, which can be conducted under general anaesthesia and includes both anorectal and vaginal assessments, plays a pivotal role in diagnosing internal rectal prolapse. If it’s performed under general anaesthesia, the gynaecological position is preferred, differently the lateral decubitus or four-legged position it’s possible with a combined vaginal and rectal evaluation performed in dorsal decubitus. The classification of rectal prolapse is based on the Oxford classification, which comprises five grades (Table 1) [16].

| Definition | Radiological definition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal rectal prolapse (IRP) | Recto-rectal intussusception | Grade I | High recto-rectal prolapse | Descends no lower than proximal limit of rectocele |

| Grade II | Low recto-rectal prolapse | Descends into the level of rectocele but not onto anal canal | ||

| Recto-anal intussusception | Grade III | High recto-anal prolapse | Descends onto anal canal | |

| Grade IV | Low recto-anal prolapse | Descends into anal canal | ||

| External rectal prolapse (ERP) | Grade V | External prolapse | Protrude from anus | |

Table 1.

Notably, rectocele is a common finding, even in asymptomatic individuals undergoing radiological examinations. It is observed in approximately 80% of women [11] with half of these cases involving rectoceles exceeding 1 cm in size. Larger complex rectoceles, typically measuring more than 3–4 cm [3, 17], are associated with a variety of symptoms, including obstructive defecation syndrome, constipation, rectal pain, and bleeding. Patients often describe the sensation of a vaginal mass during defecation, and manual assistance through vaginal compression of the rectocele is reported in 20–75% of cases.

A multidisciplinary preoperative assessment that includes thorough radiological and instrumental evaluations assumes paramount importance in the management of rectal prolapse. Equally crucial is the multidisciplinary discussion of cases, involving collaboration with gynaecologists, urologists, proctological specialists, and pelvic surgeons [3].

When urological or gynaecological symptoms are present, a focused evaluation becomes imperative, potentially leading to the consideration of combined surgical interventions, particularly in cases involving anterior uro-vaginal prolapse.

The preoperative instrumental evaluation comprises several key components [3, 18, 19]:

Colonoscopy: this procedure is essential to rule out other potential causes of rectal bleeding, such as polyps or tumours, particularly when a recent and negative endoscopy report is not available.

Defecography or Dynamic-MRI: defecography stands as the preferred radiological test due to its ability to capture the natural positioning during the examination. However, radiological imaging is unnecessary when dealing with external prolapse. The dynamic-MRI, if performed by an expert radiologist in pelvic floor imaging, is the best imaging for the evaluation of the elitrocele, enterocele, sigmoidocele, epiplooncele, and rectocele. For the internal rectal prolapse, the dynamic defecography, if performed by an expert radiologist, is, in our experience, the best radiological evaluation.

Manometry: manometric assessment proves valuable in cases of reducible prolapse. It enables a functional evaluation of the sphincters and the identification of any alterations in the coordination between the rectal and sphincter muscles, such as anismus. In cases where anismus is detected, preoperative biofeedback rehabilitation is recommended, with resolution sought before proceeding with surgery [14].

Transanal Echography: this evaluation is employed to assess the integrity of the anal sphincter if there exists any suspicion of a possible sphincter lesion or an abnormal sphincter hypotonia at the anorectal manometry was found.

Colic Transit Time: in situations involving severe constipation that could not be referred to as obstructive defecation syndrome, colic transit time assessment is performed to facilitate a differential diagnosis from obstructive defecation syndrome [1] or a combined situation of colic constipation and obstructive defecation syndrome; in the case of presence of colic constipation, a medical treatment is mandatory. A gastroenterological follow-up is usually performed to allow an improvement of the colic constipation. A new patient assessment will be performed to evaluate the persistence of obstructive defecation syndrome caused by a pelvic floor disorder.

Peripheral neurological disease may necessitate the inclusion of pudendal nerve motor latency testing and other relevant neurophysiological assessments in patient evaluations.

Several absolute contraindications, particularly for the abdominal surgical approach, merit careful consideration [3]:

Pregnancy: surgical intervention during pregnancy is not advisable.

Absence of Anatomical Abnormality: in cases where there is no identifiable anatomical abnormality, surgery should be avoided.

Severe Intrabdominal Adhesions: the presence of extensive intrabdominal adhesions poses a significant contraindication.

Active Proctitis: surgical intervention is not recommended in the presence of active proctitis.

Psychological Instability: patients with significant psychological instability, as indicated in the literature [20], may not be suitable candidates for surgery.

For some conditions, there are relative contraindications that warrant consideration, including:

High-Grade Endometriosis: high-grade endometriosis should be evaluated carefully, and the decision for surgery should be made judiciously.

Previous Pelvic Radiotherapy: patients with a history of previous pelvic radiotherapy should be assessed individually to determine the appropriateness of surgical intervention.

Previous Complicated Sigmoid Diverticulitis: a history of complicated sigmoid diverticulitis should also be taken into account when considering surgery.

To resume, in our experience the preoperative patient assessment is based on several key points steps (Table 2).

| When | |

|---|---|

| Personal medical history with particular attention to past gynaecological history and pelvic-floor surgical history Evaluation of the patient’s medical treatment | Always |

| Carful clinical examination that includes the abdominal and pelvic examination of the perineal region, the anorectal, and vaginal examination. Rigid anoscope or rectoscopy. | Always The diagnosis of rectal prolapse is fundamentally clinical |

| Clinical examination under general anaesthesia | If the standard clinical evaluation does not allow a complete evaluation |

| Colonoscopy | If we do not have a recent endoscopic evaluation or in the presence of newly appeared rectorragia In presence of solitary rectal ulcer |

| Defecography performed by an expert radiologist | To diagnose internal rectal, prolapse, and rectocele |

| Dynamic-MRI performed by an expert radiologist | Better in case of elitrocel, sigmoldocel, enterocel, epiplooncel, rectocele, and major rectal prolapse |

| Manometry | Useful in case of internal prolapse with ODS and/or rectocele at elitroclele |

| Trans anal echography | If a sphincteric lesion is suspected, in case of incontinence with a past medical history of gynaecological surgery and suspicion of an obstetrical lesion |

| Colic transit time | If a colic constipation is suspected |

| Pudendal nerve motor latency | In the case of concomitant neurologic pathology |

| Discussion of the case in a multidisciplinary setting | Always |

| Urodynamic evaluation | In case of concomitant urological symptoms |

Table 2.

Key steps of the preoperative evaluation.

3. Surgical treatment options

The definitive treatment for rectal prolapse is exclusively surgical. However, the absence of robust results from large prospective randomised controlled trials has led to a lack of international consensus regarding the gold-standard surgical intervention for both internal and external rectal prolapse [12, 13]. Currently, the ventral mesh rectopexy, as described by D’Hoore, is considered a leading approach in the field [9].

Two primary surgical approaches are commonly employed: the abdominal approach and the perineal approach [21]. While the literature documents over a hundred surgical techniques, we will focus our attention on those that are most widely practiced both in everyday surgical procedures and in published literature. In Table 3 there is a list of the most discussed surgical approaches in international literature. We will focus our attention on the three most performed procedures as you should see later.

| Abdominal approach | Perineal approach |

|---|---|

| Ventral mesh rectopexy D’Hoore | Perineal recto-sigmoidectomy – Altemeier technique |

| Posterior mesh rectopexy | Rectal mucosal sleeve resection – Delorme technique |

| Orr-Loygue rectopexy | Anal encirclement Thiersch |

| Resection rectopexy | Perineal suspension fixation – Wyatt |

| Anterior suture rectopexy |

Table 3.

The most common surgical procedures ordered based on the surgical approach.

Non-operative management is typically reserved for individuals who are not suitable candidates for surgery. This approach relies on interventions such as a high-fibre diet, laxative therapy, enemas, and biofeedback rehabilitation [1, 21].

The selection of the optimal surgical approach hinges on achieving the best functional outcomes, minimising recurrence rates, and reducing post-operative comorbidities. Regrettably, the existing literature lacks prospective randomised studies capable of conclusively identifying the superior approach [1, 3, 5]. In the randomised studies published within the last decade [3, 5], the perineal approach exhibited a non-significantly higher recurrence rate. Furthermore, in terms of functional results and improvements in quality of life post-surgery, both randomised studies conducted by Senapati et al. [5] and Smedberg et al. [3] failed to detect any significant differences. A prospective trial by Emile et al. [22] showed a non-statistically significant increase in recurrence rates and longer post-operative hospital stays following Delorm’s procedure.

In conclusion, no single procedure demonstrates clear superiority in functional outcomes and post-operative morbidity. However, data suggests that the abdominal approach may be more suitable for young, healthy patients with a lower risk of general anaesthesia-related complications. The perineal approach, on the other hand, may be reserved for elderly and more frail patients who can undergo spinal or epidural anaesthesia [1, 21].

The perineal surgical approach principally encompasses two procedures: full-thickness rectal resection with colo-anal anastomosis (Altmeier procedure) and circumferential mucosal resection (Delorm’s procedure).

Various abdominal procedures involve rectal mobilisation with rectopexy [1], with or without sigmoid resection [23]. Some authors have proposed rectal mobilisation without pexy, but a multicentre randomised controlled trial by Karkas et al. [24] demonstrated a significantly higher recurrence rate at 5 years after non-rectopexy versus rectopexy (8.65 vs. 1.5%, p = 0.003).

A subset of surgeons suggests concomitant sigmoid resection (Frykman-Goldberg procedure) during rectopexy to reduce post-operative constipation compared to preoperative and non-resection rectopexy; this procedure is more commonly performed in the United States clinical practice [1]. In Europe, resection rectopexy is not commonly performed due to an increased risk of colorectal anastomotic fistula and the availability of less risky surgical options with similar outcomes. We do not have experience in resection rectopexy that we decide not to perform considering the higher risk of complications.

Rectal mobilisation can be performed anteriorly or posteriorly. A study by Aitola et al. [25] demonstrated that posterior mobilisation worsens constipation or leads to de novo constipation. Other publications suggest that anterior mobilisation is associated with less constipation [3]. Consequently, posterior rectopexy is considered an obsolete and abandoned technique [1].

The anterior rectopexy, or Ripstein technique, and its subsequent variants were first described in 1959 [1]. The physiological and anatomical objective is to restore the rectum’s anatomical position and correct pelvic floor descent [1, 26].

Rectopexy can be executed using non-absorbable sutures or a mesh. However, a meta-analysis by Lobb et al. [26] failed to establish that mesh rectopexy significantly reduces recurrence rates. The lack of robust results in this regard can be attributed to the heterogeneity of the studies included in the analysis.

During rectal mobilisation in rectopexy, the lateral ligaments should either be preserved or divided. The division may lead to denervation and damage to the parasympathetic component of the inferior hypogastric plexus, potentially resulting in a higher rate of post-operative constipation [1].

Regarding abdominal procedures, the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach has gained popularity since the introduction and standardisation of the ventral rectopexy procedure by D’Hoore [27].

In conclusion, the most widely favoured surgical procedure for rectal prolapse treatment is minimally invasive ventral mesh rectopexy [1]. Within the perineal approach, Delorm’s and Altmeier’s procedures are the most frequently performed [1].

3.1 Altmeier’s procedure

The rectosigmoid resection with colo-anal anastomosis, performed via a perineal approach, was initially described by Mikulicz in 1889 [28]. This surgical procedure can be conducted under locoregional anaesthesia, which carries a relatively low surgical risk.

The patient is positioned in a modified lithotomic position with splayed arms. At the time of incision, a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen (comprising Cefazolin and Metronidazole) is administered, along with a low-dose heparin treatment [3, 29].

A urinary catheter is inserted and left in place for a duration of 48 hours. The use of a Lone-Star divaricator is essential as it allows for optimal exposure of the anal region, facilitating the coloanal manual anastomosis.

The procedure commences with an incision made in the rectal wall, positioned approximately 15 mm above the dentate line in the lower rectum. This incision is full-thickness and extends to the opening of the Douglas space. Subsequently, both the rectum and sigmoid colon are mobilised through this incision. In the posterior aspect, the mesorectum and mesosigmoid are ligated and subsequently sectioned. The peritoneum layer is closed using absorbable sutures, while the posterior muscular plane is sutured using non-absorbable sutures.

The anastomosis is executed via separate full-thickness sutures, typically employing Vicryl 2 or 4/0 sutures. We recommend the placement of four cardinal points, which are carefully tensioned with the assistance of the Lone-Star divaricator, followed by the positioning of additional sutures to ensure the creation of an optimal anastomosis.

Furthermore, the anastomosis should be of a mechanical nature. In such cases, the rectal wall is incised 3 cm above the dentate line to avoid anastomosis directly on the dentate line, as this could potentially lead to chronic pain.

3.2 Delorm’s procedure

The Delorme’s procedure involves the mucosectomy of the prolapsed rectum, followed by a muscular layer plication and a muco-mucosal anastomosis. Delorme first described this technique [28].

The patient’s positioning and perioperative measures are the same as those employed for the Altmaier procedure.

The procedure begins with a circumferential incision made approximately 15 mm above the dentate line. Subsequently, the mucosa is separated from the circular muscular layer, corresponding to the internal sphincter. Typically, this detachment of the mucosa is achieved through electrocoagulation. An instrument is used to grasp the mucosa, and traction is applied with a finger within the prolapsed lumen. Once adequate mucosal dissection is achieved, the muscular layer is repositioned and sutured, typically using separate stitches. The muco-mucosal anastomosis commences with four cardinal stitches and is then completed with additional stitches to ensure a comprehensive anastomosis.

3.3 Ventral mesh rectopexy

The ventral mesh rectopexy is currently the most frequently performed surgical technique for rectal prolapse and was initially described in 2005 by D’Hoore et al. [27]. This minimally invasive surgical approach is widely accepted. The original description of ventral rectopexy, known as the Orr-Loygue technique, involved full rectal mobilisation and suturing of two meshes onto the antero-lateral wall [19]. However, full rectal mobilisation has been largely abandoned due to its negative impact on functional outcomes.

The patient is positioned in a modified lithotomic decubitus with arms placed alongside the body. A urinary catheter is inserted, which can be removed post-surgery.

At the time of incision, a broad-spectrum antibiotic is administered, and a low-dose heparin is given [3].

The laparoscopic column is placed on the left side of the patient, while the second surgeon may be positioned on the right side or the opposite side [28].

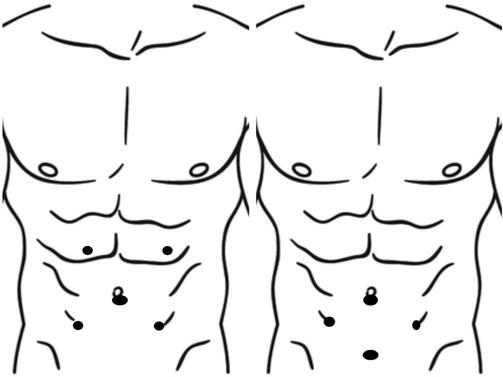

A periumbilical optic trocar placement is carried out, and pneumoperitoneum is induced either through an open technique or by inserting a Verres needle at the Palmer point in the left hypochondrium. Three or four operative 5 mm trocars are placed, with specific trocar placement varying based on surgeon preference (Figure 3). A 30° scope is recommended, although some authors have used a 0° scope as well [28]. A three trocars procedure is also possible with the suspension of the uterus, but a suboptimal exposure will be achieved with this operative setting.

Figure 3.

Trocar placement.

The sigmoid colon descends into the pelvis and should be secured with an omental flap attached to the left abdominal wall [28]. In non-hysterectomized women, transparietal fixation of the uterus is performed to free up the pelvis. A malleable valve of a laparoscopic pence is used to expose the rectovaginal space.

The patient is placed in a Trendelenburg position at 20° or 25°, with a 10° tilt. The rectosigmoid junction is retracted to the left, and an inverted-J incision is made on the right side of the rectum, over the deepest part of the Douglas pouch. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the hypogastric nerve. Dissection proceeds along the anterior rectal wall in the rectovaginal septum, with special attention to avoiding vaginal or rectal injury. No lateral or posterior dissection is performed. The anterior dissection is continued right to the elevator muscular plain; this step is useful to perform an intraoperative rectal or/and vaginal exploration to evaluate the completeness of the dissection. A non-absorbable polypropylene 3 × 17 cm mesh is secured to the anterior wall of the distal rectum with 3 up to 6 separate non-absorbable sutures. Some authors as Maggiori et al. [9] use a quite bigger mesh 4 × 20 cm. The mesh is also fixed to the sacral promontory using non-absorbable sutures or non-absorbable tacks [30]. Proper suspension of the rectum is crucial to avoid excessive tension and potential functional complications [3]. The posterior vaginal wall is sutured to the anterior aspect of the mesh, allowing for the closure of the rectovaginal septum and correction of vaginal prolapse; this is not a mandatory aspect in our experience and it can be avoided.

Closure of the peritoneal flap is performed using running sutures or separate stitches. This step is essential to prevent adhesions, obstructions, and reduce the risk of recurrence and symptomatic elitrocel [3]. In our experience, we use a 3–0 barbed V-Loc™ reabsorbable suture.

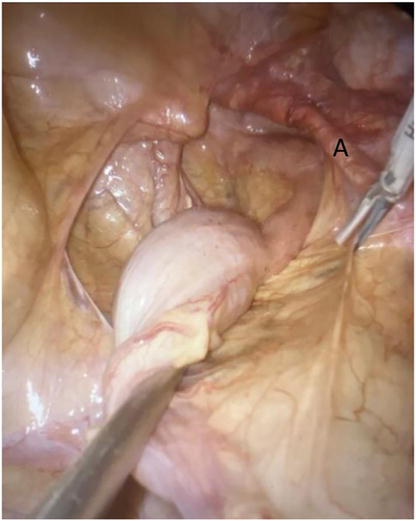

This technique, as reported by D’Hoore et al. [27], achieves a recurrence rate of 5% with a median follow-up of 5 years. The median recurrence rate for anterior mesh rectopexy varies in the literature from 0 to 16% (Figure 4) [26].

Figure 4.

Case of recurrent internal rectal prolapse with symptomatic rectocele in hysterectomised patient. Beginning of the J incision of the peritoneum at the right side of the rectum. At right side, we can remark the presence of the previous mesh.

Studies have evaluated the efficacy of biological mesh versus non-absorbable synthetic mesh. While no randomised trials directly compare the two options, some meta-analyses suggest no significant difference in post-operative complications and recurrence rates [2]. However, biological mesh tends to be more expensive. Conversely, a review conducted in 2008 by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reported a higher failure rate with biological mesh (23 vs. 9%) compared to synthetic mesh [30]. Relative indications introduced in 2013 by a panel of experts [3] recommend the use of biological mesh in specific situations, such as young adolescents or patients of reproductive age, diabetics, smokers, or those with a history of pelvic irradiation, or in cases of intra-operative injury to the rectum or vagina.

Regarding synthetic mesh, two primary mesh materials have been tested: polyester and polypropylene. Polyester mesh was associated with a significantly higher rate of erosion [31]. Moreover, synthetic mesh erosion rates were 1.87% for polypropylene compared to 0.22% for biological mesh. In our experience, we prefer a polypropene mesh. We do not have experience in this field with biological mesh; considering the experience with this type of mesh in some abdominal wall procedures, we find the manipulation of this mesh in a minimally invasive setting not easy.

In the initial description of the surgical technique, a synthetic suture was used to secure the mesh to the rectum [32]. However, it was found that a polydioxanone sulphate (PDS) 2–0 suture had a 0% erosion rate, whereas a polyester suture (Ethibond) had a 3.7% erosion rate [31]. Some authors have also explored the use of tissue glue (cyanoacrylate or synthetic hydrogel) to secure the mesh to the rectum, showing promising results, but further analysis is required. In our experience, we use a 2–0 PDS suture.

In cases of abdominal adhesions, the same surgical procedure can be performed via laparotomy.

The minimally invasive robotic approach has been evaluated in recent years. A retrospective study by Dumas et al. [33] found a longer operative time but significantly shorter hospital stays, higher patient satisfaction, and lower recurrence rates. Another meta-analysis published in 2021 showed no difference in post-operative outcomes but a shorter hospital stays [34]. Although a longer operative time is often reported, this finding was not confirmed by Flynn et al. [34]. Conversely, a meta-analysis conducted by Albayati et al. [35] comparing the two minimally invasive approaches found no difference in outcomes, but the robotic approach did require a longer operative time.

A technical variation of the ventral rectopexy that we start performing recently is the ventral mesh rectopexy with the retroperitoneal tunnelization of the mesh; this technique allow to avoid the complete lateral opening of the peritoneum with the J incision preserving both lateral and utero-sacral ligaments. Two separate incisions of the peritoneum are performed: the first at the sacral promontory and the second at the Douglas to open the recto-vaginal plain. A laparoscopic instrument is passed in the retroperitoneal space between the two incisions to create a retroperitoneal tunnel to allow the passage of the mesh. In the retrospective analysis performed by Campenni et al. [36], comparing the tunnelization technique with the classic ventral rectopexy, the modified tunnelization technique seems to be safe and faisable.

4. Outcomes and complications

Surgical complications associated with rectal prolapse repair can be categorised into inadequate technique-related issues, procedure-specific complications, and general medical complications that may occur during hospitalisation. Addressing the first two categories, the treatment could require a laparoscopic revision surgery or a conservative treatment. Technical errors identified in revision surgery, as reported by some authors [30], include insufficient evidence of ventral dissection or inadequate fixation of the mesh to the rectum or promontory.

Mesh-related complications can arise, such as mesh erosion into the rectal, vaginal, or bladder walls, particularly in patients who have undergone hysterectomy. This erosion may result in the palpable presence of mesh during rectal or vaginal examinations. The incidence of erosion can reach up to 7% with synthetic mesh but remains at 0% with biological mesh [30].

Another mesh-related complication is rectal stricture [30], which manifests as obstructive defecation syndrome and/or pelvic pain. The study by Badrek-Al Amoudi [30] attributed this complication to inadequate mesh fixation at the mid-sacrum rather than at the promontory.

Chronic pelvic pain is a rare complication that may be linked to pudendal nerve irritation. Establishing the exact cause can be challenging, but it may be associated with chronic inflammation.

Recurrence rates reported in the literature range from 0 to 16% [26], with most recurrences occurring within the first 2–3 years. The duration of follow-up is a key consideration in interpreting these rates. In a study conducted by D’Hoore et al. [27] the recurrence rate was 5% at 5 years, consistent with published literature. Maggiori et al. [9] reported a similar range, with a recurrence rate of 6% and a median follow-up of 42 ± 7 months.

A structured training program to ensure proper technical execution of the surgery is essential. The learning curve, as recognised by the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, typically comprises around 25–30 procedures [31]. As discussed by Badrek-Al Amoudi [30], the learning curve may influence both functional outcomes and complication rates. However, Trompetto et al. [29] reported a prolapse rate exceeding 40% after 4 years of follow-up following Altmeier’s procedure.

In a meta-analysis comparing abdominal ventral rectopexy with the perineal approach (Delorme and Altmaier techniques) published in 2022 by Pellino et al. [37] a higher recurrence rate was observed with the perineal approach, particularly in studies with longer follow-up periods. This difference was statistically significant in non-randomised trials but not in randomised trials. The study also found that the rate of post-operative incontinence was higher with the perineal approach, while the rate of constipation was higher with the abdominal approach.

5. Conclusions

Rectal prolapse presents a complex anatomical condition that frequently leads to debilitating symptoms and a decline in overall quality of life. Internal rectal prolapse is commonly accompanied by the presence of a rectocele. The typical clinical syndrome that leads the patient to a specialistic evaluation can include more frequently an incontinence in case of external prolapse and the obstructive defecation syndrome in case of internal rectal prolapse. When these symptoms are evident, a surgical intervention is the most viable solution. A preoperative tailored evaluation is mandatory to achieve a good post-operative functional outcome; a multidisciplinary discussion of each case is the most appropriate way to achieve the best patient selection. In case of suspicion of anisme, a preoperative well-performed rehabilitation by biofeedback is essential to achieve a favourable functional outcome.

Currently, the most effective technique and the ones that we suggest in terms of recurrence rate and the enhancement of functional aspects and quality of life is ventral mesh rectopexy, a procedure that can be safely carried out through minimally invasive settings by laparoscopic or robotic approach [9]. In case of contraindication for medical or anaesthesiologic reasons or in case of adhesions or any difficult and too risky intrabdominal surgical condition, a perineal procedure can be preferred. In this case, according to our experience, the Altmeier is preferred in case of major external prolapse and a Delorme procedure in case of minor external rectal prolapse but there a no study in literature that demonstrates the superiority of one of two techniques.

References

- 1.

Gallo G et al. Consensus statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): Management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2018; 22 (12):919-927. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-018-1908-9 - 2.

Faucheron JL, Trilling B, Girard E, Sage PY, Barbois S, Reche F. Anterior rectopexy for full-thickness rectal prolapse: Technical and functional results. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015; 21 (16):5051-5053. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5049 - 3.

Mercer-Jones MA et al. Consensus on ventral rectopexy: Report of a panel of experts. Colorectal Disease. 2014; 16 (2):1431-1433. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12415 - 4.

El-Dhuwaib Y, Pandyan A, Knowles CH. Epidemiological trends in surgery for rectal prolapse in England 2001-2012: An adult hospital population-based study. Colorectal Disease. 2020; 22 (10):1359-1366. DOI: 10.1111/codi.15094 - 5.

Senapati A et al. PROSPER: A randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 (7):858, 861, 865-867. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12177 - 6.

Joshi HM et al. Histological and mechanical differences in the skin of patients with rectal prolapse. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2015; 30 (8):1117-1122. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-015-2222-x - 7.

Attaallah W, Akmercan A, Feratoglu H. The role of rectal redundancy in the pathophysiology of rectal prolapse: A pilot study. Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research. 2022; 102 (5):289. DOI: 10.4174/astr.2022.102.5.289 - 8.

Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2020; 14 (1):39-46. DOI: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1708718 - 9.

Maggiori L, Bretagnol F, Ferron M, Panis Y. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy: A prospective long-term evaluation of functional results and quality of life. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2013; 17 (4):431-436. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-013-0973-3 - 10.

Gluck O, Matani D, Rosen A, Barber E, Weiner E, Ginath S. Surgical treatment for rectocele by posterior colporrhaphy compared to stapled transanal rectal resection. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12 (2):1-3. DOI: 10.3390/jcm12020678 - 11.

Zbar AP, Lienemann A, Fritsch H, Beer-Gabel M, Pescatori M. Rectocele: Pathogenesis and surgical management. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2003; 18 (5):369-384. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-003-0478-z - 12.

Agnès Sénéjoux. Rectocèle, entérocèle et élytrocèle : diagnostic et prise en charge. POST’U. 2023:300-302 - 13.

Van Iersel JJ, Paulides TJC, Verheijen PM, Lumley JW, Broeders IAMJ, Consten ECJ. Current status of laparoscopic and robotic ventral mesh rectopexy for external and internal rectal prolapsed. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016; 22 (21):4978-4984. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i21.4977 - 14.

Picciariello A et al. Obstructed defaecation syndrome: European consensus guidelines on the surgical management. British Journal of Surgery. 2021; 108 (10):1150-1152. DOI: 10.1093/bjs/znab123 - 15.

Formisano G et al. Update on robotic rectal prolapse treatment. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11 (8):706. DOI: 10.3390/jpm11080706 - 16.

Tsunoda A, Takahashi T, Yagi Y, Kusanagi H. Rectal intussusception and external rectal prolapse are common at proctography in patients with mucus discharge. Journal of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. 2018; 2 (4):139-144. DOI: 10.23922/jarc.2018-003 - 17.

Wong MTC, Abet E, Rigaud J, Frampas E, Lehur PA, Meurette G. Minimally invasive ventral mesh rectopexy for complex rectocoele: Impact on anorectal and sexual function. Colorectal Disease. 2011; 13 (10):e320-e326. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02688.x - 18.

Fu CWP, Stevenson ARL. Risk factors for recurrence after laparoscopic ventral rectopexy. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2017:179. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000710 - 19.

Smedberg J, Graf W, Pekkari K, Hjern F. Comparison of four surgical approaches for rectal prolapse: Multicentre randomized clinical trial. BJS Open. 2022; 6 (1):1-3, 10-11. DOI: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrab140 - 20.

Marceau C, Parc Y, Debroux E, Tiret E, Parc R. Complete rectal prolapse in young patients: Psychiatric disease a risk factor of poor outcome. Colorectal Disease. 2005; 7 (4):360-365. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00762.x - 21.

Formijne Jonkers HA et al. Evaluation and surgical treatment of rectal prolapse: An international survey. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 (1):115, 118-119. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03135.x - 22.

Emile SH et al. Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy vs Delorme’s operation in management of complete rectal prolapse: A prospective randomized study. Colorectal Disease. 2017; 19 (1):50-53. DOI: 10.1111/codi.13399 - 23.

Tou S, Brown SR, Nelson RL. Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 2015 (11):5. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001758.pub3 - 24.

Karas JR et al. No Rectopexy versus Rectopexy following rectal mobilization for full-thickness rectal prolapse: A randomized controlled trial. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2011; 54 (1):29-34. DOI: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fb3de3 - 25.

Aitola PT, Hiltunen K-M, Matikainen MJ. Functional results of operative treatment of rectal prolapse over an 11-year period. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1999; 42 (5):655-660. DOI: 10.1007/BF02234145 - 26.

Lobb HS, Kearsey CC, Ahmed S, Rajaganeshan R. Suture rectopexy versus ventral mesh rectopexy for complete full-thickness rectal prolapse and intussusception: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2021; 5 (1):1-3. DOI: 10.1093/bjsopen/zraa037 - 27.

D’Hoore A, Cadoni R, Penninckx F. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for total rectal prolapse. British Journal of Surgery. 2004; 91 (11):1500-1505. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.4779 - 28.

Lechaux D, Lechaux J-P. Trattamento chirurgico del prolasso rettale completo dell’adulto. EMC – Tecniche Chirurgiche Addominale. 2014; 20 (3):1-16. DOI: 10.1016/S1283-0798(14)68235-8 - 29.

Trompetto M, Tutino R, Realis Luc A, Novelli E, Gallo G, Clerico G. Altemeier’s procedure for complete rectal prolapse; outcome and function in 43 consecutive female patients. BMC Surgery. 2019; 19 (1):1. DOI: 10.1186/s12893-018-0463-7 - 30.

Badrek-Al Amoudi AH, Greenslade GL, Dixon AR. How to deal with complications after laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: Lessons learnt from a tertiary referral Centre. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 (6):707-712. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12164 - 31.

Mercer-Jones MA, Brown SR, Knowles CH, Williams AB. Position statement by the pelvic floor society on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland on the use of mesh in ventral mesh rectopexy. Colorectal Disease. 2020; 22 (10):1429-1435. DOI: 10.1111/codi.13893 - 32.

Collinson R, Wijffels N, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for internal rectal prolapse: Short-term functional results. Colorectal Disease. 2010; 12 (2):97-104. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02049.x - 33.

Dumas C et al. Is robotic ventral mesh rectopexy for pelvic floor disorders better than laparoscopic approach at the beginning of the experience? A retrospective single-center study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2023; 38 (1):216. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-023-04511-9 - 34.

Flynn J, Larach JT, Kong JCH, Warrier SK, Heriot A. Robotic versus laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2021; 36 (8):1621-1631. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-021-03904-y - 35.

Albayati S, Chen P, Morgan MJ, Toh JWT. Robotic vs. laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for external rectal prolapse and rectal intussusception: A systematic review. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2019; 23 (6):529-535. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-019-02014-w - 36.

Campennì P, Marra AA, De Simone V, Litta F, Parello A, Ratto C. Tunneling of mesh during ventral rectopexy: Technical aspects and long-term functional results. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12 :294. DOI: 10.3390/jcm12010294 - 37.

Pellino G et al. Abdominal versus perineal approach for external rectal prolapse: Systematic review with meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2022; 6 (2):1-3, 5, 7. DOI: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrac018