Goligher’s classification.

Abstract

Hemorrhoidal disease (HD) is a condition characterized by enlarged normally present anal cushions or nodules accompanied by clinical symptoms. HD of grade I and II, is primarily treated conservatively with medication (creams and phlebotonics) as well as by office-based procedures, such as rubber band ligation, injection sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, cryotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation. Indications for a surgical treatment of hemorrhoidal disease are: persistent and recurrent bleeding that does not respond to conservative treatment and office-based interventions, prolapse of hemorrhoids causing significant difficulties and discomfort (Grade III and IV), failure of conservative treatment methods, presence of complications (anemia, infection, or fistula). There are two types of surgical interventions, non-excisional and excisional. The group of non-excisional surgical procedures includes: stapled hemorrhoidopexy, Doppler-guided ligation of hemorrhoidal arteries and laser treatment of hemorrhoids. The group of excisional surgical procedures includes: open (Milligan-Morgan) hemorrhoidectomy, closed (Ferguson’s) hemorrhoidectomy Ligasure and Harmonic hemorrhoidectomy and Park’s hemorrhoidectomy. Non-excisional surgical methods represent potential options in the treatment of stage III hemorrhoids and patients with early stage IV disease. Non-excisional methods are characterized by lower postoperative pain intensity, faster recovery, and fewer postoperative complications, but they are also associated with a significantly higher rate of recurrence.Excisional methods in surgical treatment represent the method of choice for stage IV hemorrhoidal disease. They are characterized by intense postoperative pain and a higher frequency of complications such as bleeding, urinary retention, anal canal stenosis or stricture, and anal incontinence. There is no single best and most effective method for treating hemorrhoids.

Keywords

- hemorrhoidal disease

- surgical treatment

- non excisional surgical procedure

- excisional surgical procedures

- complications

1. Introduction

Hemorrhoidal disease (HD) is a condition characterized by enlarged normally present anal cushions or nodules accompanied by clinical symptoms [1]. The prevalence of the disease varies depending on the data from the literature, but it is considered that 5% of the total world population over the age of 18, or 50% of individuals over the age of 50, experience various symptoms of HD. It is estimated that 90% of general population suffers from haemorrhoidal symptoms at least once in their life. The rectal bleeding incidence in human population related to haemorrhoidal bleeding is around 20% per year, compared to all kinds of rectal bleeding, while the prevalence of haemorrhoidal disease, according to different studies, varies between 4.4% and 86% It is more common in men than in women. In the United States, over 2.2 million outpatient visits for patients with hemorrhoidal disease are conducted annually [2].

The primary function of the hemorrhoidal plexus is to protect the anorectal muscles and ensure a complete closure of the anal canal during rest. Filled with blood, they assist in maintaining continence, especially during the retention of gas and liquid stool. During defecation, when straining occurs, they fill with blood and descend, acting like cushions in the upper part of the anal canal, thus protecting it from a mechanical injury. Regarding the pathophysiology of hemorrhoidal disease, there are several theories, but the most accepted one is the Thomson theory, which explains the development of the prolapse or “sliding” of anal cushions caused by weakening or laxity of the Treitz muscle due to the loss of elastic fibers, while hypertrophy and congestion of the vascular tissue occur secondarily [3, 4].

In everyday clinical practice, the most commonly used classification for staging hemorrhoidal disease is Goligher’s classification (Table 1) [1].

| Grade | Physical findings |

|---|---|

| I | Prominent hemorrhoidal vessels, no prolaps |

| II | Prolaps with Valsalva and spontaneous reduction |

| III | Prolaps with Valsalva requires manuel reduction |

| IV | Chronically prolapsed manuel reduction ineffective |

Table 1.

In 2009, Nystrom and colleagues improved this classification by using a five-point questionnaire to assess the frequency of pain, discomfort, itching, staining of underwear (soiling), and the need for manual reduction of hemorrhoids. The frequency of symptoms was divided into four degrees: “never,” “less than once a week,” “1–6 times a week,” and “daily” [5]. This classification system for hemorrhoidal disease has a limitation in that it does not capture the quality of life experienced by patients with hemorrhoidal symptoms. To address this limitation, Giordano and colleagues developed a questionnaire that measures bleeding, prolapse, need for manual reduction, pain, and discomfort during defecation (as a measure of quality of life) using scores ranging from 0 to 4. A score of 0 indicates no symptoms, while a score of 20 represents the most severe symptoms [6]. In 2019, Havard modified Nystrom’s classification by replacing manual reduction with the frequency of hemorrhoidal prolapse occurrence. This modification makes it more adaptable to Goligher’s classification [7].

The treatment includes:

Conservative treatment measures (diet, lifestyle changes, application of antihemorrhoidal creams or suppositories, phlebotonics, etc.).

Office-based procedures (sclerotherapy of hemorrhoids, rubber band ligation, cryotherapy).

Surgical interventions, including non-excisional procedures (stapled hemorrhoidopexy, Doppler-guided arterial ligation, laser treatment) and excisional procedures (conventional hemorrhoidectomy, open Milligan-Morgan, closed Ferguson, submucosal hemorrhoidectomy according to Parks), are reserved for high-grade hemorrhoids when the conservative treatment has failed or complications have arisen [4].

Hemorrhoidal disease of grade I and II, according to the European Society of Coloproctology, is primarily treated conservatively with medication (creams and phlebotonics) as well as by office-based procedures, such as rubber band ligation (RBL), injection sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation, cryotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation [2]. The most commonly performed office-based procedure is rubber band ligation, as it has the lowest incidence of recurrent symptoms and the lowest need for retreatment. It is a relatively safe and painless procedure with minimal complications [8]. Additionally, in everyday proctology practice for patients with grade I and II hemorrhoidal disease, sclerotherapy is used, which involves injecting various sclerosing agents (such as 5% phenol, polidocanol foam, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, etc.) [9]. Only 10% of patients out of the total number of affected individuals with hemorrhoidal disease undergo surgical interventions.

Indications for a surgical treatment of hemorrhoidal disease:

Persistent and recurrent bleeding that does not respond to conservative treatment and office-based interventions.

Prolapse of hemorrhoids causing significant difficulties and discomfort (Grade III and IV).

Failure of conservative treatment methods (dietary modifications, topical creams or suppositories, and office-based procedures).

Presence of complications (anemia, infection, or fistula) [1].

2. Types of surgical interventions

2.1 Non-excisional procedures

2.1.1 Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH)

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) is a non-excisional procedure used in the treatment of hemorrhoids, initially introduced by Allegre in 1990 and later further developed by Maria Pecatoria [10]. However, it was Antonio Longo who achieved a widespread recognition of this method in 1998. It is also known as the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH) [11]. The treatment involves using a specialized stapler to excise the rectal tissue, specifically the mucosa and submucosa above the hemorrhoidal nodes, while preserving them and simultaneously lifting them upwards, creating a pexy of the hemorrhoids to prevent prolapse without disrupting the continence mechanism. Additionally, it reduces the arterial blood flow to the hemorrhoids and improves venous drainage [12].

The stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) procedure was developed as a response to the commonly used excisional techniques, such as the Milligan-Morgan and Ferguson procedures, in the treatment of hemorrhoids. The advantage of stapled hemorrhoidopexy is that it is associated with lower postoperative pain intensity and faster recovery. However, a drawback is that it has a higher recurrence rate compared to traditional hemorrhoidectomy. Numerous meta-analyses have compared the outcomes of stapled hemorrhoidopexy and conventional hemorrhoidectomy. One such study is the research by Burch et al. [13], which analyzed 27 randomized controlled trials involving 2279 patients. This study showed that SH was associated with lower postoperative pain intensity but had a higher rate of recurrence and the need for reintervention due to recurrent prolapse of hemorrhoids [13]. The results from the Cochrane Database published in 2010 confirmed the findings of the previous study and demonstrated a significantly higher recurrence rate after SH compared to conventional hemorrhoidectomy, as well as a higher need for additional surgical intervention during a longer-term follow-up [14].

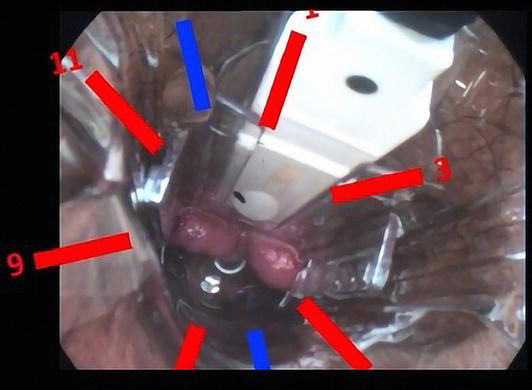

In comparison to Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation (DGHAL) or transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization (THD), stapled hemorrhoidopexy (SH) shows similar results regarding overall postoperative complications and patient satisfaction. However, the percentage of recurrence in the short-term follow-up is higher in Doppler-guided ligation of hemorrhoidal arteries, while there are no differences in the long-term follow-up, as shown by the results of a meta-analysis comprising eight randomized controlled trials involving 977 patients (Figures 1–3) [15].

Figure 1.

Pre op hemorrhoids grade III.

Figure 2.

PPH stapler with excised a ring as “donut” of redundant rectal mucosa and submucosa.

Figure 3.

After SH.

There are data in the literature describing varying frequencies of complications, ranging from 12.7% to 36.5%, following stapled hemorrhoidopexy. These complications may include: rectal bleeding, acute and chronic pain, thrombosed external piles, fecal impaction, proctitis, anal fissure, stricture, local abscess and fistula, perirectal hematoma, infections, complete rectal obliteration, rectovaginal fistulas, perforations, fecal incontinence, etc. Therefore, caution should be exercised when performing this procedure due to the potential risks and management of postoperative complications [16, 17, 18, 19].

2.1.2 Doppler-guided ligation of hemorrhoidal arteries

Doppler-guided ligation of the terminal branches of hemorrhoidal arteries is a non-excisional surgical method used in the treatment of hemorrhoids. It is based on reducing the arterial blood flow to the hemorrhoids by identifying the terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery using Doppler ultrasound and consecutively selectively ligated. This is based on the theory that hemorrhoids occur when there is an imbalance in blood flow of the hemorrhoidal plexus. By arterial ligation the inflow is reduced, causing the plexus to diminish and the hemorrhoids to shrink. The Doppler identification of hemorrhoidal blood vessels was first used in 1993 by Jaspersen and colleagues during the sclerotherapy of hemorrhoids [20]. However, the first application of ligation of the branches of the hemorrhoidal artery for the treatment of hemorrhoids was performed by Kasumasa Morinaga in Japan in 1995. Excellent outcomes were reported in 50 out of 52 treated patients (96%). The surgeries were performed using the Moricorn device [21]. Subsequently, other devices have appeared on the market such as the KM 25 device, HAL-Doppler instrument, and more recently the transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization (THD) instrument, promoted by Carlo Ratto from Italy [22].

Recent research in the field of surgical anatomy has shown that there are typically 6–10 (average 8) terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery. Ligating these branches leads to reduced arterial blood flow, decreased pressure within the hemorrhoidal node, and regeneration of connective tissue, resulting in a reduction in prolapse, bleeding, and other symptoms. The smaller branches of these arteries form a plexus in the corpus cavernosum recti. The procedure is performed using a set consisting of a proctoscope with a Doppler probe and absorbable suture (2–0) with a curved surgical needle (5/8). The Doppler probe is used to identify the terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery at two specific locations:

Above the dentate line in the muscular layer of the rectum, at a distance of 4–6 cm from the anorectal junction.

As well as at the site where it is most superficially positioned, at a distance of 1–2 cm above the dentate line.

Placement of the proctoscope in the patient in the lithotomy position, carefully advancing it up to 7 cm proximal to the rectum (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

THD slide® proctoscope.

Figure 5.

Proctoscope inserted in the anal canal and the most frequent position of terminal branches of a hemorrhoidal is superior-marked in red.

The course of the branches of the hemorrhoidal artery starts from the muscular layer of the upper part of the lower third of the rectum and descends to the dentate line, where it becomes the most superficial and suitable for ligation. The identification of these points of ligation is performed using Doppler ultrasound, and they serve as the access points for ligating the blood vessel and, if necessary, for performing mucopexy in cases of hemorrhoid prolapse [23]. There can be variations in the pathway of the branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery, making the use of a probe necessary for precision and speed during ligation.

There have been a number of studies on THD which show its early efficacy and safety for all grades of hemorrhoids, and recently THD has been acknowledged by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a safe and efficient alternative to conventional hemorrhoidectomies in Great Britain [24].

There are numerous publications on the application of Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal dearterialization, some of which are presented in Table 2.

| Authors | Type of procedure | Type of study | Number of patients | Grade of HB | Follow up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song et al. [15] | DGHAL1 vs. SH2 | Meta analysis | 977 | II–IV | 3–36 months | Lower frequency of postoperative bleeding with DGHAL, but higher recurrence rates vs. SH |

| Denoya et al. [25] | THD3 vs. CH4 | Double blind RCT | 40 | III–IV | 14 days | Decreased postoperative pain after THD |

| Sajid et al. [26] | THD vs. SH | Systematic review | 150 | — | — | Similar results, with less intensity of postoperative pain after THD |

| Brown et al. [27] | HAL5 vs. RBL6 | RCT | 370 | II–III | 12 meseci | HAL higher intensity of post-op pain, lower percentage of recurrence, compared to RBL |

| Simillis et al. [28] | THD vs. SH THD vs. CH | Systematic review | 291 203 | III–IV | — | THD and SH were associated with decreased postoperative pain and faster recovery, but higher recurrence rate. CH resulted in fewer hemorrhoid recurrence |

Table 2.

Publications of comparative analysis of Doppler hemorrhoidal dearterialization.

Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation.

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy.

Transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization.

Conventional hemorrhoidectomy.

Hemorrhoidal artery ligation.

Rubber band ligation.

In relation to patient satisfaction with THD, a retrospective study was conducted at our Department which included 70 patients with grade III et IV hemorrhoids, as well as grade II hemorrhoids, in whom the conservative treatment failed. The patients were contacted by phone 6 months after the surgery. In the course of this study we recorded the following parameters: gender, age, grade of hemorrhoids, duration of hospitalization, type of anesthesia, duration of the surgery, patient satisfaction, the combination of THD with other procedures and surgical complications. The results showed that 62.9% of the participants were satisfied, 27.1% moderately satisfied and 10% unsatisfied with this procedure [29].

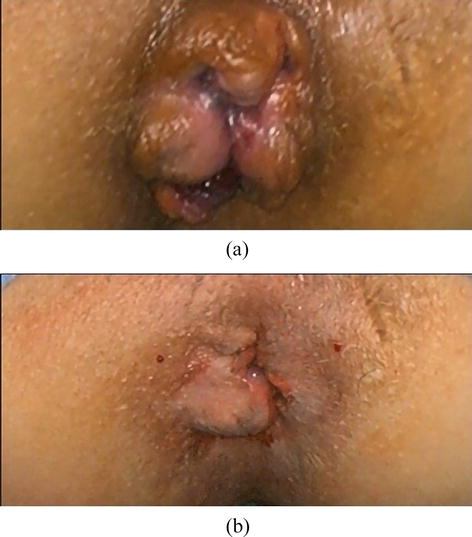

Doppler-guided ligation of the terminal branches of hemorrhoidal arteries is not a completely painless procedure, especially when combined with mucopexy. Despite its popularity and the lower intensity of postoperative pain, THD is a procedure burdened with complications, primarily recurrence. Carlo Ratto, who pioneered this method, analyzed the results of 1000 operated patients in a study conducted in 2017 with a follow-up period of up to 5 years. About 10% of patients in the present series experienced recurrence of hemorrhoidal disease following the primary THD. The most significant risk factors for recurrence were identified as stage IV disease, patients under the age of 40, and high ligation of blood vessels (Figure 6) [30].

Figure 6.

(a) Before THD and (b) after THD.

Apart from recurrence, other complications are also described in the literature: postoperative bleeding, moderate pain, rarely constipation urinary retention and perianal fissure. Berkel and coauthors described brain abscess after THD as a case report 2013, as the most severe complication [31].

2.1.3 Laser treatment of hemorrhoids

The use of lasers in proctology began in the 1960s. Initially, CO2, pulsed, and scanned lasers were used as an adjunct to open hemorrhoidectomy to address increased postoperative pain. It was observed that a laser treatment resulted in reduced postoperative pain and esthetically more pleasing scar tissue. In 2000, Plapler et al. [32] conducted studies on submucosal diode laser treatment in rats, which showed minimal changes in the interstitial tissue of the anal region. They also demonstrated that lasers could be used as a new surgical method for treating hemorrhoidal disease in primate tissue [32].

Laser Hemorrhoidoplasty, also known as Hemorrhoidal Laser Procedure (LHP and HeLP), was described by Plapler et al. [33]. It is based on the endovascular application of laser energy to the hemorrhoidal tissue, which leads to the destruction of submucosal blood vessels and their replacement with fibrous tissue, without damaging the mucosa. It is indicated for hemorrhoids of stages II and III, while for prolapsed hemorrhoids, it is recommended to be combined with mucopexy. The results of the laser energy application begin to be visible after 4 weeks from the surgery [33].

The HeLP procedure has shown, based on prospective studies that mostly included patients up to stage III of the disease, that intraoperative bleeding occurred in 8.7% of cases, which was resolved with sutures without the need for postoperative blood transfusion or blood product replacement. Postoperative bleeding was observed in 2.12% of patients, resulting in extended hospitalization, but none of them required blood transfusion or blood product replacement. Pain and analgesic use were minimal compared to open hemorrhoidectomy [34].

Based on prospective studies predominantly including patients with stage II and III disease, the LHP procedure has also demonstrated significantly less postoperative pain, minimal use of analgesics, negligible intraoperative bleeding, and no postoperative bleeding compared to open hemorrhoidectomy. However, described complications include postoperative edema (1.47%), abscess formation (0.36%), burns (0.73%), and the occurrence of skin tags (0.92%).

Laser procedures for the treatment of hemorrhoidal disease have been shown to be an effective therapeutic option for stage II and III cases, while in stage IV cases, they have demonstrated similar recurrence rates to open hemorrhoidectomy. They have been found to reduce hospital stay duration, have fewer postoperative complications, as well as lower incidence of urinary retention and anal stenosis [35].

2.2 Excisional procedures

2.2.1 Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy

Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy continues to be the gold standard in the treatment of stage III and IV hemorrhoids. The technique was pioneered in 1937 by two surgeons, Edward Campbell Milligan and Clifford Naughton Morgan, at St. Mark’s Hospital in London [36].

The method involves the excision of hemorrhoidal nodules through a careful dissection technique between the mucosa and submucosa on one side, and the muscular layer on the other side. Dissection is performed to reach the root of the hemorrhoids, where the terminal branch of the superior hemorrhoidal artery is ligated. It is essential to leave “bridges” between the excised parts of the hemorrhoids to prevent stenosis or subtotal stenosis of the anal canal. This technique is primarily used for the removal of stage III and IV hemorrhoids at the 3, 7, and 11 o’clock positions, resulting in a “three-leaf” clover appearance after excision (Figure 7) [37].

Figure 7.

Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, appearance of the “three-leaf” clover.

However, Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy is associated with significant postoperative complications, including more intense pain, bleeding, longer hospital stay, anal canal stenosis, and the risk of anal incontinence. Numerous publications have examined the advantages and disadvantages of excisional procedures in the treatment of hemorrhoids. Simillis et al. [28] published a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2015, which included 98 randomized controlled trials involving 7827 patients. The results showed that classic hemorrhoidectomies (open and closed) were associated with higher intensity of postoperative pain, complications, and slower recovery, but significantly lower recurrence rates compared to other methods [28]. Regarding patient satisfaction, a French study demonstrated that out of 482 patients who underwent classical hemorrhoidectomy or Milligan-Morgan procedure, 90% were satisfied or very satisfied, and 93% responded that they would choose the same procedure again (Table 3) [41].

| Guidelines | Grade | Level of evidence; grade of recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Belgian consensus guideline on the management of hemorrhoidal disease [38] | III–IV | Agreement 100%. Grade A. |

| Consensus statement of the Italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of hemorrhoidal disease [39] | III–IV | Level of evidence: 1; Grade of recommendation: A |

| ASCRS Practical Guidelines for Management of Hemorrhoids [2] | III–IV | Grade of recommendation: strong recommendation based on high-quality evidence, 1A |

| Japanese Practice Guidelines for Anal Disorders I. Hemorrhoids [40] | III–IV | Grade of recommendation, A |

Table 3.

Guidelines for good clinical practice with the level of recommendation for Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy.

The surgeon’s choice of specific procedures in the treatment of hemorrhoids depends on personal experience and patient preferences. An interesting study from the Netherlands published in 2018 analyzed a survey among 133 colorectal surgeons and specialists regarding their preferred methods for treating stage IV disease: 2% would perform laser therapy, only 21% would choose hemorrhoidopexy, 10% would opt for Doppler-guided ligation of hemorrhoidal vessels and mucopexy, 21% would prefer stapled hemorrhoidopexy, and 37% would still choose traditional hemorrhoidectomy [42]. It is clear that the choice of method varies for stage IV disease and, according to many, also for stage III disease, as demonstrated in a study by Altomare et al. published in 2018, which analyzed 34,000 patients operated on between 2000 and 2016 by 18 colorectal surgeons [43].

Therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly explain to the patient the advantages and disadvantages of excisional procedures through the process of obtaining informed consent prior to the surgical intervention.

2.2.2 Ferguson’s hemorrhoidectomy

Ferguson’s excisional hemorrhoidectomy is a similar method to the previous one, first published in 1955 in the United States by James Ferguson. The operation is performed in a very similar manner to the Milligan Morgan procedure, with the difference being greater preservation of the mucosa and closure of the edges of the previous excision with absorbable sutures, along with simultaneous ligation of the terminal branch of the superior hemorrhoidal artery (Figure 8) [36, 44].

Figure 8.

Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy.

Numerous published studies have focused on potential differences and similarities between these two methods. One of the well-known studies is a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 13,526 patients conducted by Bhatti et al. and published in 2016. The results are presented in Table 4 [45].

| Clinical characteristics | Milligan-Morgan (open) | Ferguson (closed) |

|---|---|---|

| Postop pain | More intense | Less intense |

| Wound healing | Worse | Better |

| Bleeding | More | Less |

| Recurrence | ns* | ns |

| Postop complications | ns | ns |

| SSI | ns | ns |

| Lengths of stay | ns | ns |

Table 4.

Differences between Milligan Morgan and Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy.

Non-significant.

Regardless of the existing minimal differences, Ferguson’s hemorrhoidectomy also represents the gold standard for the treatment of stage III and IV hemorrhoids.

2.2.3 Ligasure and Harmonic hemorrhoidectomy

Excision of hemorrhoidal nodes can be performed using scissors, a knife, monopolar or bipolar cautery, radiofrequency knife, and more recently, Ligasure and Harmonic devices. The Ligasure system for vessel sealing has proven to be a very effective method in reducing pain compared to traditional hemorrhoidectomy. The technique allows for complete coagulation of vessels up to 7 mm in diameter, with a minimal thermal spread. The thermal spread is limited to 2 mm of the adjacent tissue, which prevents anal spasm and reduces pain (Figures 9 and 10) [46, 47].

Figure 9.

Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy.

Figure 10.

(a) Before and (b) after Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy.

This treatment method is relatively new and has shown a low recurrence rate, as well as a reduction in postoperative pain, without a clear difference in the occurrence of complications such as bleeding, urinary retention, stenosis, or abscesses [48]. A randomized controlled study on 44 patients conducted by Tan et al. [49], comparing the results of Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy with open diathermy hemorrhoidectomy, demonstrated significant advantages of Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy. A publication in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews with 12 randomized controlled trials and 1142 patients demonstrated lower intensity of postoperative pain immediately after the operation and up to 14 days postoperatively, shorter duration of the operation, less intraoperative bleeding, and statistically significantly lower frequency of urinary retentions [50].

A randomized controlled trial conducted by Tsunoda et al. [51] compared Ligasure and Harmonic devices in the treatment of 60 patients with stage III and IV hemorrhoidal disease. In the Ligasure group, the surgical procedure was statistically significantly shorter in duration, there was less blood loss, and a smaller amount of postoperative analgesics was required. The length of hospital stay, patient satisfaction, and intensity of postoperative pain were similar between the two groups [50]. In any case, the use of Ligasure or Harmonic scalpel in the excision technique yields better results compared to standard methods of hemorrhoid coagulation and cutting [51].

2.2.4 Park’s hemorrhoidectomy

Parks’ hemorrhoidectomy is a method that was first described by Sir Alan Guyatt Parks from St. Mark’s Hospital in London in 1956. It was developed as an alternative to the traditional Milligan Morgan procedure, which was associated with significant postoperative complications such as pain, bleeding, and large resection of the rectal mucosa. Parks’ approach aimed to spare the mucosa of the distal colon by performing a high ligation of the terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery. The original method involves a Y-shaped incision, measuring 3–5 cm in length, starting from the mucocutaneous junction between the mucosa of the upper anal canal and the anorectal junction. The hemorrhoidal node is dissected and separated from the muscular layer of the anal canal and rectum. The terminal branch of the superior hemorrhoidal artery is ligated. The ligated area is then covered with a mucosal flap, while the skin incision is left open for potential drainage. Parks’ hemorrhoidectomy is a relatively lengthy surgical procedure compared to other excision techniques, with a slightly higher risk of anal incontinence due to the long lasting application of the Parks self-retractor placed in the anal canal. However, the competing Milligan Morgan technique remains the method of choice to this day, and Parks’ hemorrhoidectomy could not overshadow the popularity of the open excision procedure [36].

3. Conclusion

Non-excisional surgical methods (such as stapled hemorrhoidopexy, Doppler ligations, and mucopexy of the terminal branches of the superior hemorrhoidal artery) represent potential options in the treatment of stage III hemorrhoids and patients with early stage IV disease. Non-excisional methods are characterized by lower postoperative pain intensity, faster recovery, and fewer postoperative complications, but they are also associated with a significantly higher rate of recurrence. Excisional methods in surgical treatment (Milligan-Morgan—open, Ferguson—closed, Parks’ submucosal hemorrhoidectomy) represent the method of choice for stage IV hemorrhoidal disease. They are characterized by intense postoperative pain and a higher frequency of complications such as bleeding, urinary retention, anal canal stenosis or stricture, and anal incontinence. Hemorrhoidectomy performed using Ligasure or Harmonic devices represents an alternative excisional method that reduces the intensity of postoperative pain. It is necessary to thoroughly explain to the patient the advantages and disadvantages of all potential procedures as part of the informed consent process, as the treatment of hemorrhoids should be personalized. There is no single best and most effective method for treating hemorrhoids.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Mrs. Gorjana Djordjevic, for meticulous proofreading and assistance with the English text.

References

- 1.

Lohsiriwat V. Treatment of hemorrhoids: A coloproctologist’s view. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015; 21 :9245-9252. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9245 - 2.

Bradley RD, Lee-Kong SA, Migaly J, Feingold DL, Steele SR. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeon clinical practice guidelines for the management of hemorrhoids. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2018; 61 :284-229. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001030 - 3.

Aigner F, Gruber H, Conrad F, Eder J, Wedel T, Zelger B, et al. Revised morphology and hemodynamics of the anorectal vascular plexus: Impact on the course of hemorrhoidal disease. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2009; 24 :105-113. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-008-0572-3 - 4.

Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: From basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012; 18 :2009-2017. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2009 - 5.

Nyström PO, Qvist N, Raahave D, Lindsey I, Mortensen N. Randomized clinical trial of symptom control after stapled anopexy or diathermy excision for haemorrhoid prolapse. British Journal of Surgery. 2009; 97 (2):167-176. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.6804 - 6.

Giordano P, Nastro P, Davies A, Gravante G. Prospective evaluation of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialization for stage II and III haemorrhoids: Three-year outcomes. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2011; 15 :67-73. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-010-0667 - 7.

Rørvik HD, Styr K, Ilum L, McKinstry GL, Dragesund T, et al. Hemorrhoidal disease symptom score and short health scale HD: New tools to evaluate symptoms and health-related quality of life in hemorrhoidal disease. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2019; 62 :333-342. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001234 - 8.

Ramzisham AR, Sagap I, Nadeson S, Ali IM, Hasni MJ. Prospective randomized clinical trial on suction elastic band ligator versus forceps ligatorin the treatment of haemorrhoids. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2005; 28 :241-245. DOI: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60353-5 - 9.

Cocorullo G, Tutino R, Falco N, Licari L, Orlando G, et al. The non-surgical management for hemorrhoidal disease. A systematic review. Il Giornale di Chirurgia. 2017; 38 :5-14. DOI: 10.11138/gchir/2017.38.1.005 - 10.

Pescatori M, Favetta U, Dedola S, Orsini S. Transanal stapled excision of rectal mucosal prolapse. Techniques in Coloproctology. 1997; 1 :96-98 - 11.

Longo A. Treatment of haemorrhoidal disease by reduction of mucosa and haemorrhoidalprolase with a circular stapling device: A new procedure—6th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery. MundozziEditore. 1998:777-784 - 12.

Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Systematic review on the procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (stapled haemorrhoidopexy). Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2007; 50 :878-892. DOI: 10.1007/s10350-006-0852-3 - 13.

Burch J, Epstein D, Baba-Akbari AS, Weatherly H, Jayne J, Fox D, et al. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy for the treatment of haemorrhoids: A systematic review. Colorectal Disease. 2009; 11 :233, 244. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01638.x - 14.

Lumb KJ, Colquhoun PH, Malthaner R, Jayaraman S. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010; 4 :CD005393. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005393.pub2 - 15.

Song Y, Da M, Chen H, Yang F, Zeng Y, He Y, et al. Transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization versus stapled hemorrhoidectomy in the treatment of haemorrhoids. A PRISMA-compliant updated meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Medicine. 2018; 97 (29):e11502. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011502 - 16.

Popivanov G, Fedeli P, Cirocchi R, Lancia M, Mascagni D, Giustozzi M, et al. Perirectal hematoma and intra-abdominal bleeding after stapled hemorrhoidopexy and STARR—A proposal for a decision-making algorithm. Medicine. 2020; 56 :269-281. DOI: 10.3390/medicina56060269 - 17.

Park JI. Pneumoretroperitoneum after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoid. Annals of Coloproctology. 2013; 29 :256-258. DOI: 10.3393/ac.2013.29.6.256 - 18.

McCloud JM, Jameson JS, Scott AN. Life-threatening sepsis following treatment for haemorrhoids: A systematic review. Colorectal Disease. 2006; 8 :748-755. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01028.x - 19.

Pescatori M, Gagliardi G. Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2008; 12 :7-19. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-008-0391-0 - 20.

Jaspersen D, Koerner T, Schorr W, Hammar CH. Proctoscopic ultrasound in diagnostics and treatment bleeding haemorrhoids. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1993; 36 (10):942-945 - 21.

Morinaga K, Hasuda K, Ikeda T. A novel therapy for internal hemorrhoids: Ligation of the hemorrhoidal artery with a newly devised instrument (Moricorn) in conjunction with a doppler flowmeter. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1995; 90 :610-613 - 22.

Ratto C, Donisi L, Parello A, Litta F, Zaccone G, De Simone V. Distal doppler-guided dearterialization' is highly effective intreating hemorrhoids by transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization. Colorectal Disease. 2012; 14 :e786-e789. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03146.x - 23.

Ratto C. THD doppler procedure for hemorrhoids: The surgical technique. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2014; 18 :291-298. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-013-1062-3 - 24.

Pucher PH, Sodergren MH, Lord AC, Darzi A, Ziprin P. Clinical outcome following doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation: A systematic review. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 :e284-e294. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12205 - 25.

Denoya PI, Fakhoury M, Chang K, Fakhoury J, Bergamaschi R. Dearterialization with mucopexy versus haemorrhoidectomy for grade III or IV haemorrhoids: Short-term results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 :1281-1288. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12303 - 26.

Sajid MS, Parampalli U, Whitehouse P, Sains P, McFall BMK. A systematic review comparing transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation to stapled haemorrhoidopexy in the management of haemorrhoidal disease. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2012; 16 :1-168. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-011-0796-z - 27.

Brown S, Tiernan J, Biggs K, Hind D, Shephard N, et al. The HubBLe trial: Haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL) versus rubber band ligation (RBL) for symptomatic second—An third-degree haemorrhoids: A multicentre randomized controlled trial and health-economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 2016; 20 :1-150. DOI: 10.3310/hta20880 - 28.

Simillis C, Thoukididou SN, Slesser AAP, Rasheed S, Tan E, Tekkis P. Systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing clinical outcomes and effectiveness of surgical treatments for haemorrhoids. BJS. 2015; 102 :1603-1618. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.9913 - 29.

Branković B, Nestorović M, Stanojević G, Petrović D, Mihajlović D, Golubović I. Patients ‘contentment with transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization. Facta Universitatis Series: Medicine and Biology. 2019; 21 :25-28. DOI: 10.22190/FUMB190507007B - 30.

Ratto C, Campennì P, Papeo F, Donisi L, Litta F, Parello A. Transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization (THD) for hemorrhoidal disease: A single-center study on 1000 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2017; 21 :953-962. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-017-1726-5 - 31.

Berkel AEM, Witteb ME, Koopa R, Hendrixc MGR, Klaasea JM. Brain abscess after transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization: A case report. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2013; 7 :208-213. DOI: 10.1159/000351817 - 32.

Plapler H. A new method for hemorrhoid surgery: Experimental model of diode laser application in monkeys. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2008; 26 :143-146. DOI: 10.1089/pho.2007.2121 - 33.

Plapler H, Hage R, Duarte J, Lopes N, Masson I, Cazarini C, et al. A new method for hemorrhoid surgery: Intrahemorrhoidal diode laser, does it work? Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2009; 27 :819-823. DOI: 10.1089/pho.2008.2368 - 34.

Trigui A, Rejab H, Akrout A, Trabelsi J, Zouari A, Majdoub Y, et al. Laser utility in the treatment of hemorrhoidal pathology: A review of literature. Lasers in Medical Science. 2022; 37 :693-699. DOI: 10.1007/s10103-021-03333-x - 35.

Lie H, Caesarini EF, Purnama AA, Irawan A, Sudirman T, Jeo WS, et al. Laser hemorrhoidoplasty for hemorrhoidal disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers in Medical Science. 2022; 37 :3621-3630. DOI: 10.1007/s10103-022-03643-8 - 36.

Pata F, Gallo G, Pellino G, Vigorita V, Podda M, et al. Evolution of surgical management oh hemorrhoidal disease: An historical overview. Frontiers in Surgery. 2021; 8 :2-11. DOI: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.727059 - 37.

Miligan S, Morgan C. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal with special reference to anorectal fistulae. The Lancet. 1937; 230 :1150-1156 - 38.

De Schepper H, Coremans G, Denis MA, Dewint P, Duinslaeger M, et al. Belgian consensus guideline on the management of hemorrhoidal disease. Acta Gastro-Enterologica Belgica. 2021; 84 :101-120. DOI: 10.51821/84.1.497 - 39.

Gallo G, Martellucci J, Sturiale A, Clerico G, Milito G, et al. Consensus statement of the Italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR): Management and treatment of hemorrhoidal disease. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2020; 24 :145-164. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-020-02149-1 - 40.

Yamana T. Japanese practice guidelines for anal disorders I. Hemorrhoids. Journal of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. 2017; 1 :89-99. DOI: 10.23922/jarc.2017-018 - 41.

Bouchard D, Abramovitz L, Castinel J, Suduca M, Staumont G, et al. One-year outcome of haemorrhoidectomy: A prospective multicentre French study. Colorectal Disease. 2013; 15 :719-726. DOI: 10.1111/codi.12090 - 42.

Van Tol R, Bruijnen MPA, Melenhorst J, van Kuijk SMJ, Laurents PS, Stassen LPS, et al. A national evaluation of the management practices of hemorrhoidal disease in the Netherlands. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2018; 33 :577-588. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-018-3019-5 - 43.

Altomare DF, Picciariello A, Pecorella G, Milito G, Naldini G, Amato A, et al. Surgical management of haemorrhoids: An Italian survey of over 32000 patients over 17 years. Colorectal Disease. 2018; 20 :1117-1124. DOI: 10.1111/codi.14339 - 44.

Rakinic J, Poola VP. Hemorrhoids and fistulas: New solutions to old problems. Current Problems in Surgery. 2014; 51 :98-137. DOI: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2013.11.002 - 45.

Bhatti MI, Sajid SM, Baig MK. Milligan-Morgan (open) versus Ferguson Haemorrhoidectomy (closed): A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. World Journal of Surgery. 2016; 40 :1509-1519. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-016-3419-z - 46.

Thorbeck CV, Montes MF. Haemorrhoidectomy: Randomised controlled clinical trial of Ligasure compared with Milligan-Morgan operation. The European Journal of Surgery. 2002; 168 :482-484. DOI: 10.1080/110241502321116497 - 47.

Palazzo FF, Francis DL, Clifton MA. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasure versus open haemorrhoidectomy. The British Journal of Surgery. 2002; 89 :154-157. DOI: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01993.x - 48.

Bulus H, Tas A, Coskin A, Kucukazman M. Evolution of two Haemorrhoidectomy techniques: Harmonic scalpel and Ferguson with electrocautery. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2014; 37 :20-23. DOI: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2013.04.002 - 49.

Tan KY, Zin T, Sim HL, Poon PL. Randomized clinical trial comparing LigaSure haemorrhoidectomy with open diathermy haemorrhoidectomy. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2008; 12 :93-97. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-008-0405-y - 50.

Nienhuijs SW, de Hingh IHJ. Conventional versus LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy for patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009; 21 :CD006761. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006761.pub2 - 51.

Tsunoda A, Sada H, Sugimoto T, Kano N, Kawana M, Sasaki T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of bipolar diathermy vs ultrasonic scalp el for closed hemorrhoidectomy. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2011; 3 :147-152. DOI: 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i10.147