Baseline characteristics including secondary endpoint of patient risk factors for hypoglycemia.

Abstract

Hypoglycemia occurs frequently in hospitalized patients and can lead to cardiac arrhythmia/ischemia, seizures, or death. The Louisiana Hospital Improvement Innovation Network (HIIN) requires hospitals to report incidents of hypoglycemia as a quality measure. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the incidence of hypoglycemic events and identify precipitating factors at our institution. This is an IRB-approved single-center, retrospective chart review conducted from January to December of 2022 at an academic medical center. All admitted patients who received an antihyperglycemic agent and experienced a hypoglycemic event, defined as blood glucose <50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L), within 24 hours were included. The primary outcome assessed the incidence of hypoglycemic events. A total of 2455 patients received insulin during their admission, of which 91 (3.7%) had a hypoglycemic event that met inclusion criteria. Patients were predominately male (58%) with a median age of 53 years old. A diagnosis of Type I or Type II Diabetes Mellitus was reported in 73% of patients. Basal or basal-bolus insulin was ordered in 70.3% of patients. Our institution’s yearly incidence of 3.7% is above the HIIN standard of 3%. Optimization of guidelines and order sets are proposed to help lower the incidence of hypoglycemic events.

Keywords

- hypoglycemia

- insulin

- order entry

- hospital

- complications

1. Introduction

The occurrence of hypoglycemia, defined as a blood glucose reading of less than 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), in hospitalized patients has been associated with increased cost, length of stay, and most importantly, morbidity and mortality. Recently, data suggested that more than 25% of all inpatient days are incurred by people with diabetes [1]. Management of glucose proposes a challenge as patient-specific factors must be taken into account. For example, critically ill or elderly patients may not be treated as conservatively as a stable or younger patient would be treated [1]. The NICE-SUGAR trial showed that strict glycemic control can result in increased morbidity and mortality [2]. Other risk factors for developing hypoglycemia while inpatient can include severe comorbid diseases (sepsis, impaired renal function, malignancy, liver failure, and heart failure), other endocrine disorders, types and duration of diabetes, pregnancy, low body mass index, and improvement in patient’s clinical status [3].

Symptomatic hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level less than 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) accompanied by symptoms of hypoglycemia. Symptoms can include anxiety, irritability, dizziness, diaphoresis, pallor, tachycardia, headache, shakiness, and hunger. Symptoms such as malaise, lethargy, and slurred speech can occur due to effects on the central nervous system [4]. Because of this accredited organizations around the world, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), all suggest that healthcare providers be notified when blood glucose levels are less than or equal to 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) [1] and should be the threshold to initiate treatment.

1.1 Treatment

According to the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines, hypoglycemia can be classified into three separate levels [5]. The first level is defined as blood glucose 54–70 mg/dL (3.0–3.9 mmol/L). These patients may not experience symptoms and can ingest carbohydrates to prevent progression. If the patient is listed as ‘nothing by mouth’ (NPO) alternative sources may be given (I.e., dextrose 50% in water) Level two is defined as blood glucose less than 54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L), and places patient at an increased risk for cognitive dysfunction and mortality. Lastly, level three is classified as the occurrence of a severe event (altered mental status and/or physical status). These patients should be treated with glucagon or an alternative carbohydrate source [6].

Asymptomatic or symptomatic patients who are conscious, orientated, and can tolerate oral treatment should receive a rapid-acting carbohydrate. Examples of rapid-acting carbohydrates include 15–20 mg chewable glucose tablets or 150–200 ml of orange juice, and the effect should be seen within 20 minutes [7]. Blood glucose levels can be retested every 15–20 minutes, and if still less than 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), oral treatment can be repeated up to three times. For patients who are disoriented and/or unable to take it by mouth, 15 g of glucose gel, 1 mg of intramuscular glucagon, or 10 or 50% intravenous dextrose should be administered [7].

1.2 Financial impact

In addition to patient safety, the incidence of hypoglycemia also has an impact on cost. Between January 2007 and December 2011, hospital visits from Medicare beneficiaries, because of hypoglycemia, were more than $600 million in spending, and excess medical costs increased from $8417 to $9601 [8]. Studies have revealed that the cost to the hospital is $1161 direct costs per episode with a range of $242–$579 added for indirect costs: or non-medical interventions. No matter the severity of the hypoglycemic episodes, the economic burden remains. The short-term costs (e.g., emergency room visits) and the long-term costs (e.g., cardiovascular events, cognitive issues) contribute to the total treatment costs. One study by Curkendall, et al. set out to assess the clinical and economic impact of hypoglycemia that develops during hospitalization in patients who have diabetes. This study found that patients who experienced a hypoglycemic event had higher charges up to 38.9% [9]. The cost of the hospital is not the only thing that should be taken into consideration.

1.3 University Medical Center New Orleans

University Medical Center New Orleans (UMCNO) is a 446-bed non-profit, public, research, and academic hospital located in the central business district of New Orleans, Louisiana, providing tertiary care for the southern Louisiana region and beyond. UMCNO is one of the region’s only university-level academic medical centers. UMCNO is also an ACS (American College of Surgeons) designated level-I trauma center. The hospital is operated by the LCMC (Louisiana Children’s Medical Center) Health System, accredited by the Joint Commission (TJC), and is the largest hospital in the system. UMCNO is affiliated with numerous colleges of medicine and pharmacy. UMCNO is New Orleans’ largest teaching hospital and training facility for many of the state’s physicians. Meaning that our institution plays an integral role in shaping the future of healthcare for the region.

UMCNO’s Post Graduate Year 1 (PGY1) pharmacy practice residency helps residents develop the necessary clinical pharmacy skills to help patients in their care. Part of this training includes involvement in patient safety and quality improvement initiatives. This includes training in Quality Reporting and Assessment Drug evaluation. Best practices are used to assess, improve, and make changes to medication practices at the hospital. Addressing hypoglycemia incidence at our institution is one such project.

1.4 Quality measure reporting

Adverse drug events (ADEs) in hospitals can be caused by medication errors, such as accidental overdoses providing a drug to the wrong patient, or adverse drug reactions [10]. ADEs place hospitalized patients at an increased risk of harm. Voluntary reporting and tracking of errors have served as the traditional method to detect ADEs. However, public health researchers have established that only 10–20% of errors are ever reported, and, of those, 90–95% cause no harm to patients [11]. Hypoglycemia has been identified as one of the top three preventable adverse drug reactions by the US Department of Health and Human Services [6].

The Hospital Improvement and Innovation Network (HIIN) was a national initiative from 2016 to 2022 that aimed to prevent patient harm due to adverse drug events and improve care in hospitals across the United States. The HIIN also served as precursors for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)-enacted guidelines. The HIIN had developed routine, required reporting by healthcare organizations on a statewide level for ADEs an injury resulting from the use of medication.

UMCNO has participated in the monitoring and reporting of the HIIN data for over 5 years. A benchmark of 3% or less of hypoglycemic events per 100 patients who received insulin was established. The equation used to calculate incidence can be found below.

The HIIN requires patients who have a blood glucose level of less than 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L).

Over the course of the last 3 years, numerous changes have been made to insulin order sets, admission orders, and diet insulin administration requirements for nursing staff. The benchmark at the target hospital has decreased from highs of 10 to 14% to the current range of 3–4%. The hospital should continue to implement changes that will further impact the hypoglycemia incidents; therefore, the purpose of this research is to define the yearly incidence of hypoglycemia at UMCNO and identify precipitating factors that may be contributing.

2. Methods

An Institutional Review Board-approved, single-centered, retrospective chart review was conducted at UMCNO from January to December 2022. Admitted adult patients, defined as at least 18 years of age, who received an antihyperglycemic agent were included. Antihyperglycemic agents included were insulin glargine, insulin regular, insulin lispro, and sulfonylureas. Patients were excluded if they did not have a hypoglycemic event (defined as blood glucose ≥50 mg/dL [2.8 mmol/L]), the event happened more than 24 hours after administration, or if the blood glucose recheck was ≥80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L) within 5 minutes of the original reading. A list was generated from the electronic medical record (EMR) of all patients who received an antihyperglycemic agent while admitted to UMCNO.

The primary outcome was to assess the annual incidence of hypoglycemic events at our institution during 2022. Secondary outcomes measured were patient-specific risk factors for hypoglycemia, insulin type ordered, dextrose administration, and documentation of symptomatic hypoglycemia. Symptomatic hypoglycemia was identified in the medical record through documentation within an hour of the hypoglycemic event occurring. Additional data points included baseline demographics, patient disposition, and mortality. This was a retrospective study and descriptive statistics were used to evaluate both primary and secondary endpoints. Therefore, no endpoints were calculated for statistical significance.

3. Results

There were 2451 patients who received an antihyperglycemic agent while admitted to UMCNO during the year 2022. After the application of exclusion criteria, 91 patients were eligible for analysis (Figure 1). Patients were predominately African American (n = 60, 65.9%) and male (n = 53, 58.2%) with a median age of 53 (interquartile range: 47–69.9) years old. A diagnosis of Type I or Type II Diabetes Mellitus was reported in 72.5% (n = 66) of patients. Incidence of hypoglycemia occurred most frequently on medical-surgical floors or units (n = 53, 58.2%). Most patients were discharged home (n = 47, 51.6%); however, 15.3% (n = 14) of patients died during admission, 26.4% (n = 24) were discharged to a medical facility (defined as either a rehabilitation, hospice, long-term acute care, or skilled nursing facility), and 6.7% (n = 6) left against medical advice (AMA) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Screening and inclusion.

| Baseline characteristics (n = 91) | |

|---|---|

African American White Other Asian | 60 (65.9) 22 (24.2) 8 (8.8) 1 (1.1) |

Male Female | 53 (58.2) 38 (41.8) |

| 58 (47–69.5) | |

| 73.3 (66.9–86.1) | |

Type 1 Type 2 Not diabetic | 12 (13.2) 54 (59.3) 25 (27.5) |

Floor Medical intensive care unit Surgical/Trauma intensive care unit Other | 53 (58.2) 19 (20.9) 13 (14.3) 6 (6.6) |

Home Medical facility Died AMA | 47 (51.6) 24 (26.4) 14 (15.4) 6 (6.6) |

None Liver/Kidney impairment Sepsis Multiple | 39 (42.9) 26 (28.6) 9 (9.9) 17 (18.6) |

Table 1.

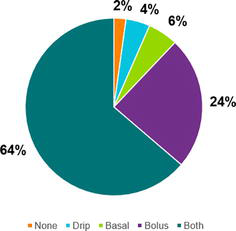

The average yearly hypoglycemia incidence was 3.7% at UMCNO (incidence per month can be found in Figure 2). A total of 57.2% (n = 52) patients had a risk factor for hypoglycemia, including kidney/liver impairment (n = 26, 28.6%), sepsis (n = 9, 9.9%), or had multiple risk factors (n = 17, 18.6%) (Table 1). Symptomatic hypoglycemia was documented in 9.9% (n = 9) of patients. Basal or basal-bolus insulin was ordered in 70.3% (n = 63) of patients, bolus insulin in 23.1% (n = 22), 4.5% (n = 4) were initiated on an insulin drip, and 2.1% (n = 2) received a sulfonylurea (Figure 3). Insulin glargine was ordered through the institutional order set 23.8% (n = 15) of the time. Thirteen percent (n = 12) of hypoglycemic events occurred in patients receiving bolus insulin for hyperkalemia.

Figure 2.

Incidence of hypoglycemia; hypoglycemic events per 100 patients receiving an antihyperglycemic agent.

Figure 3.

Break down of insulin type ordered (n = 91). Basal-bolus includes basal corrective scale orders and/or scheduled insulin with meals. “None” includes the two patients who received sulfonylurea.

Home insulin regimens were restarted in 38.4% (n = 35) of patients, with only 65.7% (n = 23) of those regimens having a dose reduction. Patient education was documented in 25.2% (n = 23) of patients. A diet was ordered in 68.1% (n = 62) of patients, while 10.9% (n = 10) had no diet ordered, and 21% (n = 19) were “nothing by mouth” (NPO). Dextrose was documented as administered to 41.8% (n = 38) of patients. Of the patients who were NPO, only 47.4% (n = 9) received dextrose.

4. Discussion

In this study, the incidence of hypoglycemia at University Medical Center New Orleans was 3.7% for the year 2022. The benchmark for hypoglycemic incidence for quality reporting is 3%. Hypoglycemic events lead to an increase in morbidity, mortality, length of stay, and cost [12], thus improvements in various areas must be made to decrease this incidence.

At our institution, clinical pharmacists evaluate every patient that is admitted to the hospital. Deferrals are implemented by our EMR system to assist the pharmacist in what needs to be addressed in monitoring including but not limited to patients’ labs, anticoagulation, antibiotic regimens, and order optimizations (IV to PO interchange) [13, 14]. Our institution currently has a deferral for hyperglycemia (Figure 4); however, previous studies have shown the implementation of best practice alerts (BPAs) and daily automated reports can decrease the incidence of hypoglycemia in the inpatient setting. Goldstein et al. conducted a study that implemented BPAs in patients who were deemed “at risk” for having a hypoglycemic episode. This study found that BPAs lowered hypoglycemia from 22.91 events/1000 patient days to 18.27 events/1000 patient days (p < 0.001). However severe hypoglycemia was not reduced [15].

Figure 4.

Example of a pharmacist deferral for a patient who has had a glucose reading greater than 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) for 2 readings or 300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L) for one reading.

After completion of the study, deferrals have been added to include a deferral for the pharmacist to review a patient’s insulin regimen if there is a blood glucose reading ≤70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). We identified that around 30% of patients did not have a diet ordered or were NPO at the time of the event; therefore, we also included a deferral for patients who were NPO or did not have a diet ordered while having an active order for insulin.

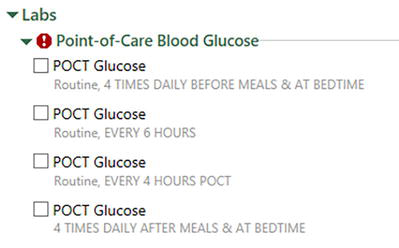

Originally, insulin glargine could be ordered without an order set through an individual drug order number (eRx). The eRx did not have administration instructions that were included in the order set, “DO NOT HOLD basal insulin when the patient is NPO unless MD is notified. CALL MD prior to administering scheduled basal insulin if BG prior to administration is less than 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L).” Also ordering insulin glargine outside of the order set did not require point-of-care glucose checks to be obtained. To address this, the insulin glargine eRx was removed from the providers’ list, allowing insulin glargine to only be ordered through the order set.

After the review of the order set was done, a forced stop was made so that a point-of-care test had to be selected (Figure 5). It was reported that home insulin regimens were restarted in 38.4% (n = 35) of patients, with only 65.7% (n = 23) of those regimens having a dose reduction. In our order set, there are areas of text space that can be utilized to help guide the provider to choose the right medication and/or dose. We decided to utilize function and add “If restarting home medication, consider a dose reduction by 25–52%.”

Figure 5.

The red stop sign with the exclamation mark allows the prescriber to know they will not be able to continue unless they select a point of care.

Our study did not directly measure the costs of hypoglycemic incidents in the hospital setting. Accounting for and estimating costs attributed to diabetes and hypoglycemia is a health behavior that affects both the presence of diabetes and the presence of other comorbidities is difficult. However, we estimate that post-interventions the number of incidents will be lowered. Thus, the cost will be less.

While only 13% of events occurred in patients receiving insulin regularly for hyperkalemia treatment, a review of the hyperkalemia order set was also done. A study by Tran et al. looked to determine the frequency of iatrogenic hypoglycemia and develop an electronic order set to decrease the risk of hypoglycemia. This study identified lower pretreatment capillary blood glucose levels, previous history of hypoglycemic events, older age, lower body weight, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) as risk factors for hypoglycemia. They also found that about 92% of events occurred 3 hours after insulin administration [16]. Our previous hyperkalemia order set did not require a point of care to be taken after administration, only before. Therefore, we included an order for mandatory glucose checks before and 2 hours after administration.

One major limitation of this study is reliance on documentation in the patient’s EMR for symptomatic hypoglycemia, if the patient received dextrose or patient-specific risk factors. Therefore, some of these could have been underreported in the study. Another limitation is that this is a single-centered retrospective chart review that could limit generalizability. While this was single-centered, the changes made to the order sets are implemented in other hospitals within the LCMC health system. This means that while our findings are institutional-specific, an impact will still be made with the changes implemented to help lower the incidence of hypoglycemia at other institutions.

5. Conclusion

The yearly hypoglycemia incidence of 3.7% is above the HIIN benchmark of 3%. Optimization to order sets has been established to lower this incidence. As mentioned previously, both the insulin and hyperkalemia order sets are system-wide. While the incidence of hypoglycemia is unknown for other hospitals in the system, changes implemented are likely to impact incidence at other institutions in the system as well. Provider and nursing education will also be established to minimize ordering and administration errors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lillian Bellfi, Pharm.D., BCCCP for her assistance with this project.

References

- 1.

Hulkower RD, Pollack RM, Zonszein J. Understanding hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients. Diabetes Management. 2014; 4 (2):165-176 - 2.

NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Liu B, et al. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012; 367 (12):1108-1118 - 3.

Pratiwi C, Mokoagow MI, Made Kshanti IA, Soewondo P. The risk factors of inpatient hypoglycemia: A systematic review. Heliyon. 2020; 6 (5):e03913 - 4.

Tomky D. Detection, prevention, and treatment of hypoglycemia in the hospital. Diabetes Spectrum: A Publication of the American Diabetes Association. 2005; 18 (1):39-44 - 5.

Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: A report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36 (5):1384-1395 - 6.

McCall AL et al. Management of individuals with diabetes at high risk for hypoglycemia: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2023; 108 (3):529-562 - 7.

Nakhleh A, Shehadeh N. Hypoglycemia in diabetes: An update on pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention. World Journal of Diabetes. 2021; 12 (12):2036-2049 - 8.

American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41 (5):917-928 - 9.

Curkendall SM, Natoli JL, Alexander CM, Nathanson BH, Haidar T, Dubois RW. Economic and clinical impact of inpatient diabetic hypoglycemia. Endocrine Practice. 2009; 15 (4):302-312 - 10.

Tsegaye D, Alem G, Tessema Z, Alebachew W. Medication administration errors and associated factors among nurses. International Journal of General Medicine. 2020; 13 :1621-1632 - 11.

Rozich JD, Haraden CR, Resar RK. Adverse drug event trigger tool: A practical methodology for measuring medication-related harm. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2003; 12 :194-200 - 12.

Cruz P. Inpatient hypoglycemia: The challenge remains. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2020; 14 (3):560-566 - 13.

Destree L, Vercellino M, Armstrong N. Interventions to improve adherence to a hypoglycemia protocol. Diabetes Spectrum: A Publication of the American Diabetes Association. 2017; 30 (3):195-201 - 14.

Mathioudakis N, Jeun R, Godwin G, Perschke A, Yalamanchi S, Everett E, et al. Development and implementation of a subcutaneous insulin clinical decision support tool for hospitalized patients. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2019; 13 (3):522-532 - 15.

Goldstein R, Odom JM. 386-P: Inpatient hypoglycemic rate reduction through the implementation of prescriber targeted decision support tools. Diabetes. 2023; 72 (Supplement_1):386 - 16.

Tran AV, Rushakoff RJ, Prasad P, Murray SG, Monash B, Macmaster H. Decreasing hypoglycemia following insulin administration for inpatient hyperkalemia. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2020; 15 (2):368-370