Abstract

This chapter examines essential paradoxes of contemporary democratic theories to overcome the present impasse of politics, such as populism, pseudo-democracy, and neo-authoritarianism. As simple democratic theory is impossible to deal with the dilemma, there is various “qualified democracy,” including participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, discursive democracy, radical democracy, agonistic democracy, contestatory democracy, and associative democracy. However, these attempts and related political philosophies contain the following tensions: (1) Deliberative democracy vs. Radial democracy, (2) Associative democracy vs. French-type Republicanism, (3) Liberalism vs. Democracy, (4) Communitarianism vs. Democracy, (5) Republicanism vs. Democracy. In order to cope with these dilemmas, this chapter will propose a new political theory, developing a democratic theory by Masao Maruyama, the most influential post-war Japanese political theorist. His idea of a “perpetual revolution of democracy” is based on the dilemma between many/individual or parts/whole along the horizontal/vertical dimension within sovereign people. This chapter will re-formulate this idea as a multi-dimensional neo-dialectical democratic theory for perpetual revolution.

Keywords

- political philosophy

- public philosophy

- communitarianism

- republicanism

- Masao Maruyama

1. Introduction: popularity and crisis of democracy as a public philosophy

Democracy is one of the most critical themes in political philosophy; moreover, it is also the cardinal theme in public philosophy.1

Public philosophy can be defined in several ways: English usage signifies philosophy, which is publicly open to many people, in other words, popular. Japanese usage focuses on philosophy concerning public and private relations [1]. Thus, this chapter defines this term in both ways: exoteric philosophy for attaining some kind of publicness. It could be described as “philosophy of the public, by the public, and for the public,” in a paraphrase of Lincoln’s famous line from his Gettysburg Address.

There are various public philosophies today: They are concerned with either politics, economy, or society. Among them, democracy is one of the most important and widespread public philosophies in its theory and application, because democracy has established itself as the orthodox public philosophy in politics in the contemporary world. Few political theorists dare to deny the cardinality of democracy. Although non-democratic regimes and practices remain in the contemporary world, rival political theories or philosophies that could directly challenge democracy have lost their attractiveness for most intellectuals: Communism or socialism lost credit, and few theorists support fascist theories and ideologies for authoritarian regimes. So then, many political theorists and citizens believed in the coming of “the third wave of democratization” (Samuel Huntington) and “the end of history” (Francis Fukuyama) in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century [2, 3].

However, this neither means that most people, including political theorists, are primarily satisfied with the present conditions of democracies in the world, nor does it mean that public policies in democratic countries are adequately responsive to various problems in the world. For example, democratic countries cannot deal adequately with economic difficulties caused by globalization, and right-wing populism has become popular even in the mother countries of Western democracy.

To begin with, American democracy has lost credit in the world, because the former Trump administration seems to be a right-wing populist government, committing various anti-democratic or illegal actions. Likewise, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson looks like a populist; Marion Anne Perrine Le Pen, a right-wing populist, challenged, though defeated by Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron, in the French final presidential vote in 2017 and 2022.

Accordingly, democracy has lost momentum in most other countries, even in countries where democracy has once established itself: there seems to be a regurgitation from democracy to authoritarian or non-democratic regimes. Some countries have degenerated into pseudo-democracies or neo-authoritarianism. Since the late 1990s, these hybrid regimes have been called illiberal democracy, semi-authoritarianism, electoral authoritarianism, or competitive authoritarianism [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Many of these hybrid regimes are substantive authoritarianism, though the country formally preserves the electoral systems. For instance, most former communist countries in East Europe have once turned into democracies, but many, including Russia, have returned to these kinds of authoritarianism or pseudo-democracies. Some Asian countries, including Japan, indicate more or less similar political phenomena.

These facts remind us that democracy failed in ancient Athens, because it degenerated into mobocracy. Likewise, democracy also failed in Germany in the Weimar Republic because of the Nazi takeover. Recent political currents above demonstrate that there still remains the danger that such nightmares could happen in the present world: democracies can collapse once again.

These crises remind us that various political theorists have already pointed to the impasse democracy faced: for example, “the deficit of democracy.” Thus, it should be recognized that democracy today is not stable and reliable at all. Although democracy is most famous as a public philosophy in the world, it is necessary to examine and revise the present state of democracy for its survival: both its theory and its practice. This chapter will focus on the normative theory of democracy, which should reflect practical political concerns in various areas.

For the revival of democracy, it is significant to examine the character of democracy, in particular, its substantive content in contrast to the formal institutions, such as the existence of elections (Section 2). Next, it matters to investigate contemporary political theories of democracy: these are frequently qualified by various attributes (Section 3). Other than these, it is worthwhile to turn our eyes to major contemporary political philosophies: liberalism, communitarianism, and republicanism. There are dialectical tensions among these political theories and philosophies (Section 4). By the examination of these philosophies, five basic tensions can be extracted (Section 5).

In order to overcome the democratic paradoxes, the following argument will call attention to the democratic theory of Masao Maruyama (1914–1996),2 the leading political theorist after the Second World War. He deeply reflected on the cultural cause of Japanese fascism and advocated establishing democracy. Moreover, he indicated original insights on democracy through his studies of Western and Japanese political thought and proposed a “perpetual revolution of democracy” (Section 6). This chapter will re-formulate this idea in contemporary political theories as a multi-dimensional democratic theory for overcoming the crises of democracy with various paradoxes (Section 7). This theory will develop Maruyama’s idea concerning radical spiritual democracy of democracy toward high-quality democracy (Section 8). Consequently, a new political theory of democracy will be proposed, and the neo-dialectical way to overcome the democratic paradoxes must be the multi-dimensional perpetual revolution (Section 9).

2. From formal democracy to substantive democracy

There can be a question of whether the notion of democracy in communist or socialist theories can be classified under a category of democratic public philosophy. Some communist theories, such as Marxist theories, historically disregarded formal democracy, and democratic centralization under the banner of the dictatorship of the proletariat in communist parties can frequently function as the dictatorial or repressive mode of domination within the parties or states ruled by the parties. As Marxist theories flourished immediately after the Second World War, this kind of criticism was significant, for example, in the age of Maruyama.

Nevertheless, such a theoretical argument against democratic centralization has been taken for granted after the collapse of the Soviet Union in many countries, including Japan. When the theme of discussion is limited to democracy in liberal regimes or liberal political activities, the legitimacy of democracy is taken for granted, and the question is, what kind of democracy should be pursued?

Formal democracy could be defined as the existence of elections and parliaments, frequently used in comparative political analyses. It is valuable and necessary to evaluate various regimes by the existence/non-existence and the substance of elections, and this is sometimes all that can be done due to the limits posed by available data in comprehensive comparative analysis.

However, the existence of elections is insufficient for maintaining and developing democracy. There are cases where elections are used to legitimize substantially authoritarian regimes. There were other cases when formal democracy collapsed, being reduced to a mere formality disguised by the existence of elections. These phenomena correspond to neo-authoritarianism or competitive authoritarianism mentioned above. In the age of mass democracy, democracy can also quickly transform into populism, authoritarianism, or even fascism, just like democracy fell into mobocracy in ancient Athens. Athenian democracy was defeated when it began to wage the imprudent Peloponnesian War with Sparta.

Moreover, formal democracy is insufficient for realizing a democratic ideal: it tends to degenerate into the façade of rule by power elites. J. J. Rousseau wrote, in

Thus, we need something more than formal democracy for the following reasons. First, the results of elections merely reflect people’s opinions at the time of elections. Secondly, the elections are sometimes manipulated by governments: their timing, issue-setting, and influences of power. Thirdly, people’s votes only express their preferences for parties and politicians and cannot accurately articulate their opinions on various issues.

Maruyama argued that democracy includes not only institutions like elections but also democratic ideas and movements [12]. The reason would be that the latter two factors are indispensable for making democracy reflect people’s opinions lively beyond the results of elections: this moment can avoid the danger of the degeneration of democracy mentioned above.

Accordingly, this chapter uses the term “substantive democracy” in contrast to merely institutional “formal democracy:” The former signifies democracy by people’s authentic opinions and their participation, based on sufficient information and discussions.

Democracy has already established itself as the orthodox public philosophy in politics, but the public philosophy should be qualified into some form of substantive democracy. It would be possible to call the qualified form substantive democracy: it implies raising the quality of democracy against degeneration under the guise of formal democracy.

3. Democracies qualified by attributes in political theories

Various theorists have proposed ideas for making democracy substantive. Maruyama’s understanding of democracy consisting of ideas, institutions, and movements is one of them. He also emphasized the importance of voluntary associations in democracy.

Some recent political theorists in the West proposed qualified democracy by adding some adjective to the word democracy: participatory democracy (Carole Pateman), deliberative democracy (Jürgen Habermas, Joshua Cohen, James S. Fishkin), discursive democracy (John S.Dryzek), radical democracy (Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe), agonistic democracy (Chantal Mouffe, William Connolly), contestatory democracy (Philip Pettit), associative democracy (Paul Hirst). These are related to arguments in public philosophy in general [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27].

Hanna Arendt and J. Habermas greatly influenced contemporary public philosophy. Arendt emphasized the importance of “action,” namely, public or political discussion and debates in human life [28]. Her works promoted critical arguments against formal democracy, and the discussions illuminated the importance of critical arguments, protests, or challenges in politics. “Participatory democracy” was proposed in the age of radical politics in the 1960s and 1970s. Rousseau’s thought typically influenced it, and Arendt’s political philosophy revived or provided a new impetus to this stream of political theory. These kinds of democratic theories especially emphasized the democracy of movements in Maruyama’s terms.

Habermas belongs to the second generation of critical theory in Germany, and his philosophy naturally contains a critical perspective toward essential aspects, such as the capitalist economy and bureaucracy in the contemporary world: he summarized the contemporary structural problem in the phrase “colonization of life world.” Against this problem, he formulated a communication theory of discursive ethics [29]. He argued that reaching a consensus is possible in an “ideal speech situation,” and his theory is regarded as a consensus model.

Political discussion, debate, and deep thinking with sufficient information or knowledge constitute one of the central elements of democracy, and these arguments stimulate political theories. Habermas’ philosophy contributed to the generation of “deliberative democracy” led by J. Cohen, J. Fishkin, and others: J.Cohen, a former student of Habermas, emphasized the deliberative process through reason and discussion normatively, and J. Fishkin proposed to introduce the deliberative process by conducting deliberative opinion poll and deliberative day before votes.

However, this kind of democracy seems to be grounded in the consensual model of politics, and this is attacked by theorists who attach importance to the conflictive aspect of politics. For example, E. Laclau and Ch. Mouffe argue for “radical democracy,” which implies deepening democracy beyond formal or consensual democracy by activating conflictive and contestatory elements in politics. A version of radical democracy is “agonistic democracy” (Ch. Mouffe, W. Connolly), which emphasizes combative politics in a democracy.

To be sure, it is crucial to turn our eyes to the conflictive elements of democracy, but the existence of this aspect does not necessarily mean the denial of the importance of the deliberative process. Thus, some theorists, like J.S. Dryzek, revised the idea of deliberative democracy into “discursive democracy” by increasing the relative weight of the conflictive aspect in the deliberative process in civil society.

While radical democracy focuses on the aspect of movement in democracy, a republican philosopher, Ph. Pettit, proposed the concept of contestatory democracy. This idea illuminates the process of contestation, but he emphasizes the institutional arrangements that enable people to utilize the process: the judiciary, ombudsman, and so on. This theory broadens the institutional variety beyond the mere electoral process.

Other theorists, such as P. Hirst, revived classical associationism and proposed “associational democracy.” He proposed that various civic associations should be activated to take charge of democratic governance in fields, such as medicine, education, and welfare: this would pluralize the state and publicize civil society. This idea is quite in tune with Maruyama’s emphasis on voluntary associations, enlarging the scope of the classical idea of associations from the political sphere to the social sphere.

Each of these ideas has advantages and disadvantages, but most have something to contribute to making democracy substantive. Deliberative democracy is vital, because deliberation provides democracy with some degree of good decisions in the policymaking process and prevents democracy from deterioration. Radical democracy, including agonistic democracy, could revive the mechanisms of defense against possible abuse of power in a democracy. However, too much emphasis on conflictual aspects could lead to sterile political battles if political actors disregard the desirability of consensus as long as possible. The idea of discursive democracy tries to balance the demands of consensual politics and those of conflictual politics. The process of discussion and deliberation is the most essential function of the public sphere, and, therefore, these democratic political theories could be regarded as the development of public philosophy in politics.

In the case of contestatory democracy, this concept is closely associated with a kind of republican public philosophy; associative democracy focuses on the associations of another kind of republican public philosophy, as will be discussed below. Thus, republicanism and related public philosophies are the theme of the next section.

4. Dialectical tensions in political philosophies: liberal, communitarian, and republican democracy

While these ideas of democracy have been principally proposed as political theories, political philosophies present noteworthy other candidates for public philosophy in politics than qualified democracies: liberalism, communitarianism, and republicanism. In fact, these three are the central concepts in recent literature of public philosophy, while democracy is more familiar in the world.

Michael Sandel, for example, attacked Rawls’ version of liberalism in his

The idea of liberal democracy is so popular that the philosophical tension between liberalism and democracy tends to pass unnoticed. Nevertheless, careful political philosophers or theorists are conscious of the tension: liberalism, especially in contemporary American political philosophy, emphasizes the importance of rights and justice and even asserts its priority over democracy when the requirements of liberalism clash with those of democracy. Thus, liberalists are not necessarily passionate democrats: liberalists are cautious about the danger that the majority’s decision infringes on the rights of the minority.

In contrast, communitarianism and republicanism are, at a glance, positively associated with democracy; in fact, these two are also prospective candidates for attaining substantive democracy, as well as the theories mentioned above. These two are set within the framework of democracy. While social conservatives or authoritarians are hostile to democracy, communitarians support democracy and strive to be respectable democratic citizens. Republicans historically contributed to establishing democracy against the monarchy and strongly hoped to maintain democracy.

However, some philosophical tensions exist between these and the simple understanding of democracy. Communitarianism stresses the importance of morality and virtue, and republicanism focuses on civic virtue, while a simple understanding of democracy does not require citizens or voters to have any particular moral or ethical quality. Ancient political philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle, initially proposed the moral or ethical requirement. Plato, for example, argued that wisdom and virtue are necessary for politics in an ideal republic. They do not necessarily rank democracy highly, because they were aware of the problem of mobocracy, which they observed in Athenian democracy after Pericles. While citizens have some level of knowledge and morality under good leadership, democracy works well; when these conditions are lost, democracy can degenerate into mobocracy, and the polity faces the danger of collapse in some way.

This historical understanding lies under the problem mentioned earlier in this article. Communitarians and republicans attempt to provide democracy with a remedy against this problem. The communitarian prescription would be the general ethical improvement of citizens. Republican proposals consist of cultivating civic virtue for political participation and political wisdom for attaining the common good, supplemented by institutional contrivance for preventing dictatorship or tyranny: Sandel’s accent on the formative project of cultivating citizen’s character for self-government corresponds to the former, and Pettit’s idea of contestatory democracy is in accord with the latter.

The naïve understanding of democracy does not imply these conditions: democracy means literally the rule by

It would be thus fruitful to propose the terms “communitarian democracy” and “republican democracy:” these are also qualified democracies inspired by political philosophy. These two kinds of qualified democracy are not equivalent to simple democracy but a form of integration between democracy and some non-democratic elements, just as liberal democracy is the connection between democracy and liberalism, which is not necessarily democratic ideas.

As communitarianism requires citizens to have some virtues, communitarian democracy introduces ethical dimensions into simple democracy. As republicanism requires citizens’ civic virtues and institutional arrangements against tyranny, republican democracy introduces civic virtue and separation of powers into simple democracy.

5. Five basic tensions among the qualified democratic theories and political philosophies

What kind of democracy could provide the normative ideal of public philosophy? Several dilemmas exist in various proposals of qualified democracies above, including communitarian and republican democracy.

5.1 Deliberative democracy vs. radical democracy

First, deliberative democracy conflicts with radical democracy, including agonistic democracy, and the two could be integrated into discursive democracy. The fundamental opposition is “consensual discussion vs. conflictual discussion.”

5.2 Associative democracy vs. French republicanism

Secondly, associative democracy is opposed to a version of republican democracy, namely, the French republican model. French republicanism has some characteristics different from republicanism in other areas, including the United States. It historically rests on a negation of the intermediary bodies of the feudal society, as it took place in the French Revolution process. It is constructed on the dichotomy of “individuals/the state,” disregarding various intermediary groups or associations between the two.

5.3 Liberalism vs. democracy

Thirdly, there is an internal tension between liberalism and democracy within liberal democracy. About abstract values or ideas, liberty (or liberal rights) is a matter of the highest priority for liberalism, while equality (or equal participation) is the top priority for democracy.

5.4 Communitarianism and democracy

Fourthly, as was discussed, some tension exists between communitarianism and democracy. The essential axis of opposition is their attitudes toward perfectionist ideas such as virtue and morality.

5.5 Republicanism and democracy

Fifthly, also as was discussed, there is tension between republicanism and democracy. The main issues of difference are the following two points: 1) the republican requirement of civic virtue and the ideal of publicness, and 2) the republican institutional arrangements against the defect of crude majoritarian rule. Sandel’s republican democracy represents the former element, while Pettit’s contestatory democracy corresponds to the latter.

If formal democracy is sufficient, there is no need to be bothered by these annoying issues. However, it is necessary to tackle these dilemmas to realize substantive democracy beyond the limits of formal democracy. It is not at all easy to give solutions to these.

6. Neo-dialectical movement of democracy: Maruyama’s insight on many and the individual

It would be helpful to recall Maruyama’s important insight here. Maruyama acknowledged that it was impossible to attain the perfect democracy and that democracy is inevitably an unfinished project. The underlying reason is as follows: By definition, in a democracy, the people governing are identical with the people governed. However, people in power are, in reality, the minority, while the governed are usually the majority. Therefore, there is always tension between the ideal of democracy and its reality: the tension between the many and the individual or between the majority and minority in the political community. As a result, there is always the danger that “people” articulated as a whole can easily be identified with the state or the leader. Democracy embraces both the vertical dimension between power and people and the horizontal dimension between the many and the individual. Consequently, the supposition of democracy comprises the dual structure of verticality and horizontality, theorized as the contract of government and the social contract in the social contract theories. Consequently, democracy is never completed, and it should be dynamically evolving toward its ideal, namely, the identity between the governing and the governed. Maruyama expressed this with the phrase “democracy as perpetual revolution” or movement [12].

The first opposition above is closely associated with this insight. The consensual model assumes the possibility of reaching agreements by ideal discussion based on reason: the consensus within the whole. In contrast, theorists supporting the conflictual model do not believe in the realization of the possibility, and they suppose that there are always different opinions and confrontations within a political community: schism between the many and the individual.

On the one hand, Maruyama acknowledged that there is always a gap between many (the governed) and the individuals (governing), and he shared, with theorists of radical democracy, the insight that protests and conflicts are inevitable. On the other hand, he shared, with theorists for deliberative democracy, the vision that the ideal of democracy is the realization of consensus by discussion, namely, the unity between many and individuals.

Accordingly, Maruyama’s view on democracy could be expressed as a dialectical synthesis between conflictive and consensual models, namely, deliberative democracy and radical democracy. The term dialectical synthesis tends to remind us of the static state of integration like Hegelian dialectics, but Maruyama’s view differs from this: he put forward the idea of democracy as a perpetual revolution. Thus, against Hegelian dialectics, the term “neo-dialectical movement or synthesization” is appropriate for expressing that perpetual dynamic process that never reaches the static state of perfection. Accordingly, Maruyama’s political theory of democracy can be termed “neo-dialectical democracy:” his vision of “democracy as perpetual revolution” can be re-formulated as a “neo-dialectical movement of democracy” or “neo-dialectical democracy of perpetual process for the synthetic ideal.”

The second tension between French republicanism and associative democracy is also associated with the opposition between many/individuals and parts/whole. The former sticks to the dichotomy between individuals and the state, while the latter emphasizes the intermediary groups that could somehow mediate between parts and the whole. Associations do not necessarily enable us to reach the synthesis between parts and the whole, but they at least constitute some kind of mediation between the two. Such mediation can be regarded as one of the main functions of the neo-dialectical process. Mature Maruyama valued voluntary associations very highly, and his view at the stage was closer to associative democracy than the typical French republicanism: his view could be described as that of neo-dialectical democracy also concerning associations.

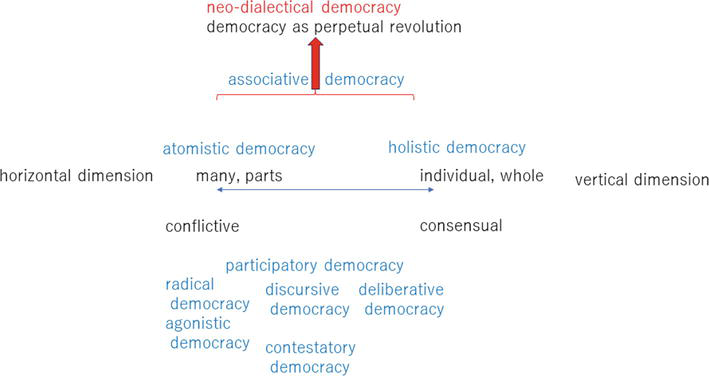

The opposition between parts and the whole almost equals the famous philosophical opposition between many and one in its substantive content. “Many” corresponds to the atomistic worldview, while “one” to the holistic worldview. Conflictual democracy corresponds to the former, and it can be characterized as the vision of “atomistic democracy;” consensual democracy corresponds to the latter, and it could be featured as a vision of “holistic democracy” typically seen in Rousseau’s idea of “general will,” although Habermas’ philosophy cannot be seen as a simple holistic theory. The idea of “neo-dialectical democracy” can be regarded as the neo-dialectical process of integration of atomistic democracy and holistic democracy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The first two tensions (many/individuals or whole/parts).

The third tension concerning liberal democracy is the opposition between liberty and equality. As Alexis de Tocqueville characterized democracy as the equalization of various conditions, such as politics, economy, society, and culture, democracy is undividedly associated with equality [33]. Liberty in liberalism, here, can be regarded as that escapes from the vertical hierarchies of power, while equality embodies the horizontal bonds of human relationships. Thus, this tension can be interpreted to be also related to that between the vertical dimension and the horizontal dimension in human relationships.

Maruyama was both a prominent liberalist and representative democrat in his age, and he could be regarded as “a neo-dialectical liberal democrat,” because he was keenly aware of this tension, while many liberal democrats are not very conscious of this.

Thus, the first three paradoxical tensions correspond to Maruyama’s conceptualization of the dialectical opposition between many and individuals along the horizontal and the vertical dimensions.

7. Multi-dimensional neo-dialectics of democracy: the horizontal, vertical, and elevational dimension

The other two tensions within democracy can also be interpreted as dialectical opposition, although these differ from the tension between many/parts and one/whole.

The fourth tension associated with communitarian democracy is the opposition between virtue and equality (or equal participation). There is an ethical or moral hierarchy inherent in perfectionism, and this is opposed to equality in that the former implies a kind of hierarchy, although it establishes itself within the moral sphere. Accordingly, this tension can be considered to be between the height dimension and the horizontal dimension in human relationships: the height dimension signifies a transcendent, spiritual, ethical, or virtuous dimension, and this can be expressed as the elevational dimension in an adjective form.

Shigeru Nanbara, the mentor of Maruyama Masao, can be regarded as a pioneering Japanese communitarian and liberalist. Maruyama succeeded the communitarian element to some extent [34, 35]. Consequently, Maruyama respected religious or spiritual values as one of the foundations of liberal democracy. Nanbara was a communitarian democrat, and Maruyama could be regarded as a liberal democrat with some communitarian element: this is associated with delicate tension in political theory, and Maruyama, without doubt, was well aware of this tension as will be made clear in the following section.

The fifth tension concerning republican democracy, on the one hand, shares this opposition (between the elevational dimension and the horizontal dimension) with the fourth tension, because civic virtue for political participation is one of a spectrum of virtues that most communitarianians respect. Accordingly, this aspect of republicanism can be called “communitarian republicanism.” This is the heir of Greek democracy, and Michael Sandel’s political philosophy can be regarded as this type.

On the other hand, the institutional arrangements against the defect of simple democracy are related to ideas of a kind of liberty against vertical authority and the tyranny of the majority. For example, contestatory democracy, propounded by Petitt, is associated with the idea of “liberty as non-domination.”: This idea was inspired by Quentin Skinner, who elucidated the republican history of ideas and formulated its core into the neo-Roman theory of free citizens and free states [36]. Accordingly, this aspect of republicanism can be termed “non-domination republicanism,” while “liberal republicanism” principally signifies the modern institutional republicanism of separation of powers unrelated to virtues. Skinner’s neo-Roman republicanism and Pettit’s non-domination republicanism are the heirs of ancient Roman republicanism. As Pettit pointed to the communitarian character of freedom and the necessity of widespread civic virtue or widespread civility in his theory [26], this kind of republicanism contains both ethical and institutionally liberal moments. Nevertheless, its ethical moment is less or thinner than communitarian republicanism.

Accordingly, the fifth tension is related to the dichotomy between the horizontal and elevational dimensions (communitarian republicanism) and vertical and a limited degree of elevational dimensions (non-domination republicanism).

Maruyama’s ideas contained conspicuously republican elements in his emphasis on political participation. Thus, he could be regarded as a republican democrat. Nevertheless, he is well-known as a representative liberalist after the Second World War. As he clearly recognized the tension between liberalism and democracy, his political theory seems to be a “neo-dialectical liberal democracy.” Therefore, his political theory is essentially “neo-dialectical republican liberal democracy.”

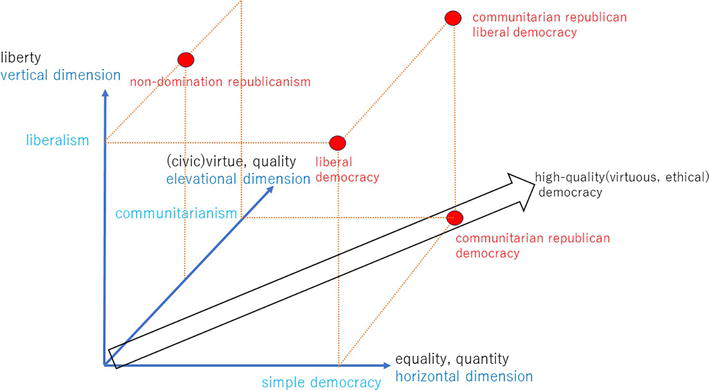

So then, these five tensions are concerned with the opposition between different dimensions. The first three tensions are concerned with the horizontal and vertical dimensions, and the third, between liberty and equality, corresponds to the vertical and horizontal dimensions. The latter two are related to the opposition between virtue and equality, the former concerning the ethical dimension and the latter regarding the horizontal dimension. In sum, these are tensions among vertical, horizontal, and elevational dimensions (Figure 2). Maruyama’s line of democratic theory would attempt to integrate these tensions neo-dialectically because these are all critical issues, so dismissing one side of each dilemma is impossible.

Figure 2.

The latter three tensions (along the three dimensions). Notes: Blue signifies dimensions and their most related political philosophies. Red signifies political theories and their locations.

8. Toward high-quality democracy: perpetual revolution for “Radical Spiritual Democracy”

The third tension between liberalism and democracy has been frequently discussed in political philosophy, although the popular political discourse often neglects this paradox in democracy. While the liberal respect of rights does not necessarily accompany democratic participation, the heated latter can menace the former. It is the well-known dichotomy of negative and positive liberty by Isaiah Berlin [37]: pursuing the latter may cause the infringement of liberty by the tyranny of the majority, exemplified in J.J. Rousseau’s idea of the general will.

This paradoxical dichotomy concerns the inherent tension within liberal democracy, the orthodox public philosophy in the contemporary world. In contrast, the fourth and the fifth tensions are significantly related to the problem of the degeneration of democracy mentioned in the first section of this chapter.

The tension between democracy and communitarianism or republicanism is related to the contrast between quantity and quality: simple democracy depends on the will of the majority, which is measured by ascertaining the quantity, namely the number of people supporting a given issue, while communitarianism or republicanism awards a place of significant importance to ethical or moral virtue or spirituality, which is concerned with the quality of human character. Simple democratic theories, including participatory democracy and radical democracy, tend not to focus on the ethical or spiritual elements concerning human quality, while communitarian or republican theorists try to do so. In short, this is the tension between quantity and quality concerning people: while simple democracy relied on quantity, communitarianism and republicanism turned our attention to quality.

Although Masao Maruyama was one of the leading liberal democrats in Japan at his age, he was sensitive to this issue, and he ended his most famous book

His point here can be expressed as “radical spiritually aristocratic democracy,” namely, “radical spiritual democracy” or “radical aristocratic democracy.” Maruyama dared to use such a paradoxical expression of connecting a kind of aristocratic mentality with democracy to emphasize the importance of introducing spiritual or ethical elements into democracy.

His argument turns our eyes to the requirement of qualitative aspects for democracy by mentioning the spiritual or aristocratic mentality. In this sense, this can be regarded as a precedent for raising the question of the quality of democracy. Communitarian and republican thinkers today have put forward this line of argument.

The purpose of such arguments as “radical spiritual democracy,” communitarian democracy, and republican democracy is to improve the quality of democracy lest democracy should deteriorate into mobocracy. Such a democracy as being of high quality can be called a “high-quality democracy.” This democracy can also be characterized as “(civic) virtuous democracy” or “(civic) ethical democracy” in the sense of democracy equipped with civic virtue.

Although this could be proposed as an abstract ideal, it is challenging to attain it in practice and to maintain the high quality even once such a democracy is established. The reason is that the tension between quantity and quality is inevitable, because there is always an unavoidable qualitative difference in people’s respective spiritual or moral capacities as human beings. As democracy means the rule of

Accordingly, it is inevitable for us as human beings to pursue the unattainable ideal perpetually. Maruyama raised the idea of a “perpetual revolution of democracy” as a means of coping with the tension between parts and the whole, and this idea applies to the endless quest for high-quality democracy, because there must be differences among various parts within the whole. This aspect can be called a “perpetual revolution for high-quality democracy.”

The tension between quantity and quality corresponds to the tension between the horizontal and elevational dimensions, and this permanent movement can be regarded as the neo-dialectical movement arising out of these two axes. The perpetual revolution for high-quality democracy is thus a neo-dialectical, ever-lasting movement or process toward radical spiritual democracy.

9. Conclusion: democracy as multi-dimensional perpetual revolution

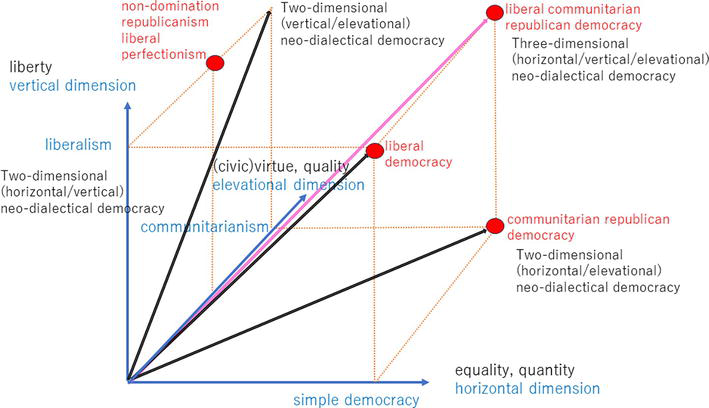

Consequently, the neo-dialectical way of qualifying democracy is vital in the last two tensions concerning communitarian or republican democracy, as it is also significant in the first three tensions associated with the tension between many/parts and individuals/whole. Maruyama himself introduced the concept of “democracy as perpetual revolution,” being conscious of the tension between many and individuals, namely along the horizontal and vertical dimensions. Moreover, he recognized another dilemma between horizontal and elevational dimensions. The recent development of theories on democracy points to the tensions concerning the elevational dimension. Accordingly, it would be desirable to apply Maruyama’s insight to all these tensions and to generalize it: his insight into democracy can be conceptualized as “neo-dialectical democracy,” and the extended version can be termed “multi-dimensional neo-dialectical democracy.”

There are three dimensions: 1. horizontal dimension concerning equality, 2. vertical dimension concerning government or liberty, and 3. elevational dimension concerning ethics and virtue.

The original neo-dialectical democracy in Maruyama’s idea, the perpetual revolution of democracy, signifies the endless dialectical democratic movement along the first two dimensions. Moreover, there are other kinds of neo-dialectical movements in democracy.

The first kind is the two-dimensional neo-dialectical democracy between the horizontal and vertical dimensions, corresponding to liberal democracy for equality and liberty. There is tension between liberalism and democracy: negative liberty and positive liberty, in other words, the rights of the minority and tyranny of the majority. This kind of neo-dialectical theory has much in common with the original Maruyama’s idea.

The second kind is the two-dimensional neo-dialectical democracy between the horizontal and elevational dimensions, corresponding to communitarian republican democracy for equality and virtue. There is tension between democracy and communitarianism/republicanism: equal participation and perfectionism, in other words, the political rights of all people and virtue/civic virtue in the ethical hierarchy.

The third kind is the two-dimensional neo-dialectical between the vertical and elevational dimensions, corresponding to non-domination republicanism. In contemporary political philosophy, this tension can be seen in liberal perfectionism for liberty and virtue. There is tension between liberalism and perfectionism: state neutrality and virtue ethics, in other words, non-ethical state and virtue. Representative theorists like Joseph Raz try to accommodate the two by limiting the concerning virtue only to autonomy [39].

Although meeting the two elements in the three tensions is challenging, there should be a neo-dialectical endeavor to balance or integrate them. These movements constitute the three-dimensional neo-dialectical democracy between the horizontal, vertical, and elevational dimensions. This democracy integrates liberal democracy, liberal perfectionism, and communitarian/republican democracy. As communitarian republicanism are perfectionist political theories, the integral democracy can be termed as liberal communitarian republican democracy: it is for equality, liberty, and virtue. Accordingly, the three-dimensionally neo-dialectical quest is required for democracy.

In sum, the paradox of democracy discussed in this chapter is three-dimensional. The initial Maruyama’s idea, the perpetual revolution of democracy, is two-dimensional; this chapter enlarged the idea into the three-dimensional “perpetual revolution of democracy,” turning into the three-dimensional neo-dialectical movement of democracy. Its fundamental ideas are horizontal equality, vertical liberty, and ethical virtue. Consequently, a new political theory of democracy, namely, the multi-dimensional neo-dialectical democratic theory, emerges (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multi-dimensional Neo-dialectical democracy. Note: See the note in

Democracy is undoubtedly the most firmly established public philosophy in politics. However, many theorists acknowledged that formal democracy is insufficient, and some proposed various forms of qualified democracy for attaining substantive democracy, as was mentioned above. Most proposals are meaningful, but each grasps some aspects of desirable democracy. Moreover, several dilemmas or paradoxes exist within the various versions of qualified democracy in political theory and philosophy. Democracy should overcome the multi-dimensional contradictions, and the process must be “democracy as multi-dimensional perpetual revolution.” This eternal movement is the vision of the multi-dimensionally neo-dialectical democracy.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Japanese-German Center Berlin for arranging the international conference mentioned in note 1. I also thank for the assistance of Hirotaka Ishikawa (graduate student of the Graduate School of Humanities and Studies on Public Affairs, Chiba University) regarding the works on the figures and references of this chapter.

References

- 1.

Yamawaki N. Glocal Public Philosophy: Toward Peaceful and Just Societies in the Age of Globalization. Zurich: Lit Verlag; 2016 - 2.

Huntington SP. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late 20th Century. Norman: The University of Oklahoma Press; 1993 - 3.

Fukuyama F. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press; 2006 - 4.

Diamond L, Linz JJ, editors. Politics in Developing Countries: Comparing Experiences with Democracy. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publication; 1995 - 5.

Zakaria F. The rise of illiberal democracy. Foreign Affairs. 1997; 67 (6):22-43 - 6.

Zakaria F. The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad. Revised ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2007 - 7.

Ottaway M. Democracy Challenged: The Rise of Semi-Authoritarianism. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Int’l Peace; 2013 - 8.

Schedler A, editor. Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Publications; 2006 - 9.

Levitsky S, Way LA. The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy. 2002; 3 (2):51-65 - 10.

Levitsky S, Way LA. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002 - 11.

Kersten R. Maruyama Masao (1914-96). London: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy; 2001 - 12.

Maruyama M. In: Morris I, editor. Thought and Behavior in Modern Japanese Politics. London: Acls History E-book project; 2008 - 13.

Maruyama M. Studies in Intellectual History of Tokugawa Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2016. Translated by Mikiso Hane - 14.

Rousseau J-J. The Social Contract. New York: Free Press; 1970 - 15.

Pateman C. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1970 - 16.

Habermas J. Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1991 - 17.

Cohen J. Deliberation and democratic legitimacy. In: Hamlin A, Pettit P, editors. The Good Polity. Oxford: Blackwell; pp. 17-34 - 18.

Cohen J. Procedure and substance in deliberative democracy. In: Bohman L, Rehg W, editors. Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1997. pp. 67-92 - 19.

Fishkin JS. Democracy and Deliberation: New Directions for Democratic Reform. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1993 - 20.

Ackerman B, Fishkin JS, editors. Deliberation Day. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2005 - 21.

Dryzek JS. Deliberative Global Politics: Discourse and Democracy in a Divided World. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2006 - 22.

Dryzek JS. Discursive Democracy: Politics Policy and Political Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994 - 23.

Mouffe C. The Return of the Political (Radical Thinkers). London/New York: Verso Books; 2006 - 24.

Connolly WE. Pluralism. Durham: Duke University Press; 2005 - 25.

Connolly WE. Identity/Difference: Democratic Negotiations of Political Paradox. London: University of Minnesota Press; 2002 - 26.

Pettit P. Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1997 - 27.

Hirst PQ. Associative Democracy: New Forms of Economic and Social Governance. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers; 1994 - 28.

Arendt H. The Human Condition. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998 - 29.

Habermas J. The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1.2. Cambridge: Polity; 1991 - 30.

Sandel MJ. Liberalism and the Limit of Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982 - 31.

Mulhall S, Swift A, editors. Liberals and Communitarians. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 1996 - 32.

Sandel MJ. Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1996 - 33.

de Tocqueville A. Democracy in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. Edited and translated by H. C. Mansfield and D. Winthrop - 34.

Minear RH. War and Conscience in Japan: Nambara Shigeru and the Asia-Pacific War. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc; 2010 - 35.

Kobayashi M, editor. Maruyama Masao Ron: Shutaiteki Sakui Fashizumu Shimin Shakai (Discussing Maruyama Masao: Subjective Invention, Fascism, and Civil Society). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; 2003 - 36.

Skinner Q. Liberty before Liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997 - 37.

Isaiah Berlin. Liberty. In: Hardy H, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002 - 38.

Masao M. Japanese Thought. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten; 1961. pp. 179-180 - 39.

Raz J. The Morality of Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988

Notes

- This chapter originates from a conference paper "Neo-Dialectical Democracy as the Perpetual Revolution: From Qualified Democracies to High Quality Democracy," in November 28, 2007 at Berlin, Germany-Japan conference "Aspects of Democracy: Toward Solutions for twenty-first century Developments."

- See Ref. [11] as a biographical explanation. His translated works are Refs. [12, 13].

- Translation is mine.