Conceptual comparison among CoPs in the four representative studies.

Source: Matsumoto [8].

Open access peer-reviewed chapter

Submitted: 23 August 2023 Reviewed: 04 September 2023 Published: 06 October 2023

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.1002981

From the Edited Volume

Fausto Pedro García Márquez and René Vinicio Sánchez Loja

Although communities of practice (CoPs) are known to facilitate learning, boundary crossing, and knowledge creation, these effects have not been examined according to different structures in the extant literature. Thus, this chapter presents an exploratory study on how the establishment of various types and structures of communities affects the effectiveness of an individual’s learning and boundary crossing. This was an exploratory qualitative case study of an educational service company, in which data were collected using face-to-face semi-structured interviews and participative observations. Using a case study, we classified CoPs into two types based on their size and frequency of interactions: interaction and networking communities. We also conceptualized four learning styles in CoPs and investigated the relationship between the two types of communities and the four learning styles derived from previous research. We found that the CoPs examined in this study interacted with each other (through learners’ multiple affiliations with various communities) to form multilayered structures, which present advantages such as the possibility of high-level learning through multifaceted and circular learning, and the ability to build networks among communities. Therefore, we conclude that multilayered CoPs structures are effective in enhancing all four learning styles.

Communities of practice (CoPs) [1, 2, 3, 4] are known to facilitate learning, boundary crossing, and knowledge creation. However, despite such diverse outcomes, extant literature does not discuss these effects considering CoP types and structures. Several studies have discussed the need to expand the definition of CoPs (e.g., [5, 6]); however, the fragmentation of the concept has only led to confusion rather than moving the discussion forward. To help elucidate this matter, we conducted an exploratory study of how establishing different types and structures of CoPs [1, 2, 3, 4] affects individual learning and boundary crossing based on a case study of an educational service company, the results of which are presented in this chapter. Specifically, we examined how the multilayered structure of CoPs facilitated learning. Here, we attempt to organize the concept of CoPs and divide it into two broad types. We then conduct a case study to uncover and discuss how these two types of CoPs should be constructed and managed.

CoPs are defined as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” [4]. However, the content of the CoPs concept varies widely, and the usage of this term is diverse [7]. This is because previous studies relied on one of four representative studies (i.e., [1, 2, 3, 4]), between which there were differences in the content (Table 1).

| Lave and Wenger [1] | Brown and Duguid [2] | Wenger [3] | Wenger et al. [4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Can we create a CoP? | Embedded in social and historical context (already exists) | Finding and discovering CoPs within organizations | Co-exists with and found from organization | To be able to make and cultivate |

| Reproduction of CoPs | Through a common process to advance identity construction and learning | Not discussed | Reproduced by participation, embodiment, and design | Discussed in their development model |

| Operation and management | Not discussed | Not discussed | Mutual construction in each member’s practice | Discussed its importance and methods |

| Main purpose | Learning and skills transfer (practice and work in the community as well) | Understanding work, learning, and innovation from non-canonical view | Creating meaning and learning through identity construction by practice | Creating, storing, updating, and sharing knowledge |

| Elements | Communities, practice | Communities, practice | Communities, practice | Domain, community, and practice |

| Contents of members’ practices | Fulfilling participation in the community | Learning by practice (understanding work and innovation) from non-canonical view | Participation and reification in the dimensions of mutual engagement, joint enterprise, and shared repertoires | Increasing knowledge in the domain |

| What guides learning? | Curriculum of learning and curriculum of education | Promoting membership and access to the CoPs as well as storytelling, collaboration, and social construction | Practices that guide learning (participation and reification, emergence, modes of belonging, local and global) | Domain |

| Boundary crossing | Relationships that transcend boundaries are CoPs | CoPs across organizational boundaries | Practices such as boundary objects and brokering lead boundary crossing | CoPs across organizational boundaries |

| Memberships | From newcomers to experts | From newcomers to experts | Formed through participation and reification | Coordinator, core members, active members, and peripheral members |

| Member instructorship | Not discussed | Not discussed | Not discussed | Instructorship of coordinator is important |

| Identity | Construction of learner’s identities progresses simultaneously with participation | Practical-based view transforms organizational identity | Guided by participation and non-participation | CoP is a “home of identity” |

| Relationship between CoPs and organizations | Close to identical, but not the same | Distinguish between formal organizations and CoPs; the relationship between the two is important | Separate but overlapping | Distinguishes between formal organizations and CoPs, and presents the concepts of double-knit organizations |

| Horizontal relationships among CoPs | Peripheral legitimacy is the nexus between CoPs | Perceiving the organization as a set of CoPs can solve the problems of the organization | Suggesting the constellation of practice as the collection of CoPs | Suggesting distributed CoPs |

| Multilayered relationships among CoPs | Participation at multiple levels inevitably accompanies membership in a CoP | Assumes an aggregation of CoPs linking each other | Constellation is a connotation of CoP | Assumes multilayered nature with sub-communities |

Conceptual comparison among CoPs in the four representative studies.

Source: Matsumoto [8].

The conceptual diversity described above limits the development of CoPs, thus we must discuss the expansion of this concept. To address the diversity of the concept, this section focuses on size. CoPs have been proposed as primarily small places of work where members frequently interact through their practices as their style of learning [1]. Other studies have also noted the importance of learning based on interactions [9, 10]. However, another style of learning exists, in which people meet and acquire new knowledge and information through communication across workplace boundaries [11]. In this type of learning, the CoP is primarily large and infrequent, and connections and knowledge are created through boundary crossing [12, 13]. In previous studies, there has been conceptual confusion between small, frequently interacting CoPs and large, infrequent, boundary-crossing CoPs. In this chapter, we discuss how CoPs can be used more effectively by classifying them into two types.

Another issue involves high- and low-level learning. Meta-level learning has been discussed in, for example, single- and double-loop learning [14] and higher-level learning [15] studies; however, all of these studies were conducted at the organizational level and have not been discussed even at the individual level [16]. CoPs are suitable for lower-order learning, where knowledge, skills, and information are acquired, but not for higher-level learning, where existing beliefs and values behind knowledge and skills are transformed [17]. However, this is derived from a static view of the concept of a CoP, and other studies (e.g., [18]) suggest that even in a CoP, it is possible to trigger transformative learning, which leads to a change in values and perspectives [19, 20]. In this study, we examined the classification of these two types of CoPs.

It is useful to consider that the two types of CoPs are not only different in size and frequency, but also in the learning styles therein. Separating them into categories would be futile if their learning styles were the same, even if their size and frequency were different. The basic learning styles of CoPs have been presented in the previously mentioned four major studies. In this section, we organize and summarize them as the four learning styles described below.

Derived from Lave and Wenger [1], the legitimate peripheral participation learning style involves the sharing and creation of knowledge and skills through interactions among members of a CoP [1]. This style has been proposed as a learning method for newcomers to acquire knowledge and skills by fully participating in the CoP through sociocultural practices. The basic idea of legitimate peripheral participation is that new members acquire the skills of the community from existing members and develop their identities through participation [21] while becoming members of the CoP. The acquisition and creation of knowledge and skills from existing members are thought to be the primary learning style [22]. Regarding the level of learning, it is lower-level learning [17]. Legitimate peripheral participation and CoPs are inseparable, but this concept assumes a static and stable concept of CoP. Learning through legitimate peripheral participation is suitable for small communities [23] and difficult in CoPs that are large and have infrequent interactions, such as those with many subsequent boundary crossings [24] and online CoPs [25].

Multifaceted learning, derived from Brown and Duguid [2], involves acquisition of diverse knowledge and skills. This is a higher-level learning style based on the comparison between canonical and non-canonical knowledge [3]. There is often a divergence between knowledge believed to be correct in the field (canonical knowledge) and practice-based or field knowledge (non-canonical knowledge), and this difference leads to learning [3, 26] that enhances CoPs [27]. That is, using this difference helps CoP members to understand work and innovation. Moreover, this learning style incorporates values and perspectives, as well as diverse knowledge and skills acquisition in the workplace [28], public health practice [29], public office [30], and society [31].

This learning style, derived from Wenger [3], involves acquiring, sharing, and creating skills and knowledge through network interactions, that is, through interacting with external communities and their members [32]. CoPs link local human resources and knowledge [4], and the creation of human networks can be used to increase the total amount of knowledge available [33], distribute knowledge, maintain and improve its quality, and create knowledge through interactions [34], thus boundary-crossing learning is characteristic of CoPs. This style is mainly low-level learning, but sometimes, high-level learning occurs. Boundary crossing enhances collaborative learning in CoPs in three ways. First, boundary-crossing activities increase members’ diversity [35] to facilitate collaborative knowledge creation through multiple viewpoints. Second, boundary crossing encourages members to compare their experiences, knowledge, and selves, thereby facilitating new insights and knowledge. CoPs enhance this type of knowledge creation, leading to knowledge sharing [36], information gathering [37], problem-solving [38, 39], and personal career design [40, 41]. Third, boundary crossing enhances higher-level learning by, for example, generating meaning [3], emphasizing the value of work [42], promoting the understanding of members’ identities [19], and enhancing lower-level learning, including through knowledge sharing. It is possible to resolve contradictions and enhance activities by spontaneously establishing CoPs and facilitating boundary crossing. This style of learning is enhanced by extensive boundary crossing and the ability to interact with many people. Large CoPs created by social events, even if infrequent, are also effective. However, the learning effect of boundary crossing is weak when practiced with a fixed group of people.

Derived from Wenger et al. [4], circular learning is argued to be based on members of a CoP that are also members of formal organizations, and that this multimembership creates a cycle of learning. It is mainly a low-level learning style, but sometimes high-level learning occurs. The members bring their experiences and knowledge to the CoP, discuss, generalize, or document them, obtain support for problem-solving, and then apply them to real problems at their respective organizations. Multimembership is an important aspect of CoPs [42, 43]. The learning cycle between CoPs and organizations is effective [34, 44] not only for sharing knowledge [45], but also for generating transformative learning [41, 46].

We summarized the above four learning style in Table 2.

| Research | Lave and Wenger [1] | Brown and Duguid [2] | Wenger [3] | Wenger et al. [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Names and methods of learning styles | Legitimate peripheral participation | Multidisciplinary learning | Boundary-crossing learning | Circular learning |

| Learning through full participation and interaction within the CoP for knowledge acquisition | Learning from the differences between canonical and non-canonical knowledge to transform values and perspectives among organizations and CoPs | Crossing the various boundaries of organizations and CoPs to acquire knowledge and relationships with those outside the CoP | Learning through moving between one’s organization and CoP to discuss and confirm knowledge and skills |

Learning processes derived from four representative studies.

We considered these four learning styles to be effective in CoPs’ learning and examined how these learning styles relate to different types of CoPs and how they are constructed and operated. To this effect, we conducted a case study of an educational service company as described below.

To clarify learning in CoPs, we conducted a case study based on the data collected using qualitative methods. This was a single case study based on Yin’s work [47], and we selected Kumon Ltd. as the research site. Kumon is a company that provides education services for children, franchises Kumon-style classrooms, and supports children’s learning. We selected this company because it was suitable for a single case study that met all three of the following criteria: (1) the case is definitive, (2) the case is extreme and unique, and (3) the subject is a new fact [47]. Further, we selected Kumon because it enhanced diverse learning based on CoPs. Specifically, in Kumon, instructors teach children in Kumon-style classrooms using common teaching materials and form CoPs with learners and support staff in each classroom. Similarly, instructors participate in many CoPs to improve their teaching skills. The CoPs in this study meet the definition by Wenger et al. [4] and are adequate for discussing the relationship between the two types of CoPs, the four learning styles, and better management methods, consistent with the purpose of this study.

In addition, Kumon has various learning communities such as those formed through their “district meetings” at the district level and “courses” led by Kumon at the national level. Nevertheless, this chapter focuses on the following four CoPs that are more autonomously constructed and operated by instructors and have a multilayered structure: seminars and voluntary institutes in which instructors participate, seminars and voluntary institutes organized by instructors, mentor seminars, and instructors’ research conferences. Although studies dealing with multilayered structures exist, such as the study by Wenger et al. [4] focusing on global CoP, Kumon’s case is characterized not only by its inclusive scale but also by the construction of a multilayered structure based on proficiency level. We believe that this study will present new findings in existing studies.

Two survey methods were used to collect the case study data: interviews and participative observations.

Seven instructors who were teaching at Kumon with 10–30 years of work experience were selected as interviewees. As per our request, they were selected by the Kumon HRM staff after explaining the purpose of the study. The interviews were conducted face-to-face for one and a half hours using, a semi-structured form [48] and the protocols were recorded using an IC recorder and transcribed by the author. Kumon officers were sometimes interviewed and provided supplementary explanations as needed. In addition, we observed the actual instructions in some classrooms.

The participative observation survey was conducted with the cooperation of Kumon, wherein we observed two events sponsored by Kumon: the Kumon instructors’ research conference and the mentor seminar. At the instructors’ research conference, we participated in discussions of theme meetings and took notes, while at the mentor seminar, we simply observed their discussions and took notes. Subsequently, we got documents about Conference from Kumon. These observations were then used to construct a case study.

Kumon Institute of Education Co., Ltd. was established in 1962. They developed original learning materials and managed classrooms nationwide to teach mathematics, English, and Japanese as well as French, German, and calligraphy.

Kumon operates 23,700 franchised Kumon-style classrooms (for mathematics and arithmetic, English, and Japanese) at 115 office location across Japan (as of March 2023). Kumon’s classrooms are operated twice a week for approximately 5 hours per day. In their classrooms, students tackle their original educational materials independently, and instructors (teachers) support individualized learning activities. Homework is assigned each time and students are expected to complete it at home and bring it to the next class. Each instructor manages their own classroom with Kumon’s support through a franchise system. Instructors, mainly women, begin operating their own classrooms after training. Each Kumon classroom is supervised by a regional office, and the Kumon staff provide support for their classroom operations. One Kumon staff member supported approximately 50 instructors.

Kumon education emphasizes “high basic literacy,” “self-affirmation,” and “independent learning ability” to help students acquire the “zest for life.” The features of the Kumon educational method can be summarized into four points: individualized learning, self-directed learning, small-step materials, and operations by instructors and staff. First, regarding individualized learning, teachers use materials that correspond to each student’s academic ability. Even if all students are of the same age and grade, there may be differences in their abilities. This individualized attention on the students in turn improves each student’s academic ability significantly. Another feature of their individualized learning is starting with the materials level, where students are sure to score full marks, and graduating to higher-level materials step by step. By guiding students to get full marks on their educational material, instructors and staff can foster their confidence and self-affirmation, thereby increasing their motivation to learn. Improvements in the students’ academic skills encourage them to try materials at a higher level, regardless of their age or grade. It is thus common for students to study at a higher level in Kumon; for example, some third-grade students study at the fifth or sixth grade level of elementary school.

Second, self-directed learning means that Kumon does not conduct one-way education as in school education. In the Kumon classroom, each student works on his or her own material, solving problems independently and listening to the instructors’ and staff’s guidance. Third, they use small-step materials, which means the content’s difficulty level gradually increases from easy to advanced. Kumon’s teaching materials are created using the expertise gained over Kumon’s long history and are improved daily based on feedback from the classroom. This means that students can solve the material that is adequate for them, and small increments in their level ensure that their academic skills are effectively established.

The fourth factor is the guidance of the instructors and staff. Instructors and staff are indispensable for monitoring each student’s progress and supporting their learning. The instructors/staff members are aware of the students’ abilities and provide them with adequate materials. They do not move on when the student is not ready; they provide them with lower-level materials to tackle and only allow them to progress to higher-level materials when they have the academic literacy and desire to advance. This plays an important role for instructors and staff, who can objectively look at students. Recognizing, praising, and encouraging students’ efforts is essential for fostering self-directed and positive learning attitudes. Each of these four features influences the others and creates a synergistic effect. When instructors accurately understand materials that have been refined over Kumon’s long history and use them appropriately in the classroom, teaching methods based on the four aforementioned characteristics can be implemented.

We found that Kumon instructors learned from many experiences under the company concept of “learning from children” in their own classrooms, and at the same time, they are members of diverse CoPs wherein they obtain information that helps them improve their skills in and motivation for teaching and classroom management. As discussed below, the results of these CoPs have been highly positive and we believe that there is a strong relationship between learning activities and teaching performance. Furthermore, Kumon has a mechanism for forming a CoP and expanding boundaries among instructors, which we discuss later in this chapter.

How does Kumon support instructors? Kumon classrooms in each region are supervised by a branch office. For example, the Nishinomiya Office oversees the classrooms in Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture. The branch office controls the classes in the region, and instructors visit the office to pick up teaching materials for their classrooms. Instructors can easily meet the staff at the office and ask for advice on their problems. The offices are grouped into “areas” according to the wider region. The Nishinomiya Office is located in the Kansai area. Various activities are conducted within the region, offices, and areas.

The Kumon organization has a development department that is responsible for communicating about how to use Kumon’s teaching materials. They conduct lectures to transfer business knowledge and develop tools that facilitate learning. Alongside the instructional department, they also promote classroom development by improving instructors’ skills and training them. The department also publishes a magazine that provides information to instructors.

Kumon staff manage 50–60 instructors. They work with instructors to determine how classrooms should be managed. Just as a teacher understands their student, staff understand the teachers’ strengths and weaknesses and guide them appropriately on how to overcome and improve their weaknesses. This guidance is important and affects the success or failure of classroom management.

Undoubtedly, the greatest source of the excellent results produced by Kumon is the instructors’ interactions and shared learning activities and the professional development that they obtain from them. As of March 31, 2014, Kumon had consolidated sales of 86,446 million yen, ordinary income of 10,773 million yen, and 4038 employees throughout the group. In addition to 85 locations nationwide, Kumon has regional headquarters in North America, South America, Asia and Oceania, China, Europe, and Africa, and is actively developing its business in 47 countries and regions worldwide. In Japan alone, the company had 1.46 million learners (total number of learners in all subjects) in 16,500 classrooms as of March 31, 2014. The company manages these classrooms with 14,600 instructors. Overseas, there are 8400 classrooms with 2.81 million learners (total number of learners in all subjects) and 7400 instructors, and is attracting attention both domestically and internationally as a universal business model.

However, the development of instructors at Kumon is achieved through the autonomous learning of the instructors themselves, not only through the Kumon Method of Education. This is also supported by learning based on various types of CoPs that instructors spontaneously establish through Kumon. Kumon contains a system that activates the building of CoPs and learning based on these. This is the most important factor that enables Kumon to continue to develop instructors who make the most of the Kumon method and materials to steadily improve student performance.

In the following section, the CoPs formed by Kumon instructors are described in detail based on the authors’ research.

There are four types of Kumon CoPs discussed in this chapter: (1) “seminars” that Kumon instructors spontaneously conduct, (2) “small-group seminars” coordinated by Kumon, (3) “mentor seminars” conducted by skilled instructors, and (4) “instructors’ research conferences” held at the national level. Kumon has a system in which these CoPs, which differ in size, frequency, and spontaneity, are formed and operated, and they have a synergistic effect. This has improved the instructors’ teaching skills.

New instructors, who have just opened their own classrooms after receiving Kumon training, typically do not have sufficient previous experience, either as teachers or managers of their own classrooms. Therefore, they must rely on Kumon materials and support staff to manage their classrooms through trial and error. However, the instructors must manage their classrooms independently, which is challenging task.

Consequently, instructors actively participate in “seminars” to share their teaching and management knowledge in order to improve student performance and increase the number of self-motivated learners. These seminars primarily aim to explore and share teaching and management skills. They take place on days when classes are not held and are attended by approximately 20–30 instructors. The seminars are coordinated and managed by experienced instructors. Seminars authorized by Kumon are accredited: Kumon requires instructors to participate in them and submit reports thereafter, and they earn credits for their participation.

It is important for Kumon staff to use seminars for instructor development. Depending on the instructors’ need to improve their abilities, staff members introduce and encourage instructors to participate in these seminars. This is because these seminars present many teaching examples and data that can help instructors develop their own skills. Many instructors have their own instructional data. Second, it is meaningful for instructors to learn from other instructors, not only teaching skills, but also classroom management, career design, and how balancing work and family life. Therefore, it is essential for the Kumon staff to guide instructors to appropriate seminars while considering their individual characteristics and the nature of each seminar.

During seminars, the instructors hold lively discussions on issues such as day-to-day classroom management and effective teaching methods, providing their own examples as they discuss. Even instructors attending for the first time can immediately engage in discussions. Instructors not only share the same topics but also use common Kumon teaching materials, with which they are deeply familiar. For example, if someone says, “In the second question of the Japanese B-1 material…,” all the other instructors immediately understand the question and answer it with their own teaching examples. Such interactions allow them to engage in more detailed discussions and skills sharing.

For new instructors in particular, it is very important that senior instructors play the role of mentors in seminars. This is a valuable opportunity for them to solve their problems. Experienced instructors can provide varied advice, from confirming their teaching expertise to solving problems related to students who are not improving, classroom management, teaching careers, and personal concerns. After attending such seminars, new instructors often regret why they had not started participating in seminars sooner.

As instructors gain experience and proficiency in teaching, Kumon often asks them to manage their seminars. The instructors share their knowledge and skills in teaching and classroom management with the participants based on their own experiences. At first, some instructors hesitate to manage seminars, but they understand the significance of sharing their teaching skills and passing on what they have learned from senior instructors, and they accept their roles. It is common for proficient instructors to take over seminars from senior instructors or manage seminars themselves while continuing to participate in seminars to learn.

Kumon’s staff prepare seminars by arranging the venue, but they do not engage in seminars unless instructors ask them to maintain their spontaneity. This differentiates them from “small-group seminars,” which we discuss next.

Small-group seminars are CoPs coordinated by Kumon; the organization also creates its learning content. They are different from the previously discussed seminars, for which spontaneity is important. However, they are the same in that they both aim to equip instructors with good teaching skills. The background of the small-group seminar system promotes more interactive learning between Kumon and the instructors and encourages the application of learned skills and knowledge in the classrooms. Kumon ensures that instructors acquire the teaching skills that the organization has accumulated over the years.

Another characteristic that differentiates small-group seminars from seminars is that, in the former, the Kumon staff provide the lecturers and are in charge of the seminars. They lecture using the same textbook and slide materials, not only to standardize the teaching content but also to stimulate learning among staff.

Five to six instructors participated in each small-group seminar, which Kumon emphasized during the design of the system. The rationale for this is that if there are too many instructors participating, some of them might not speak up or may become too reserved, while having too few participants might make interaction between them difficult. Currently, instructors study one theme over 3 months in three sessions.

The venue for the small-group seminars is primarily the branch office. Typically, two to three small-group seminars can be held simultaneously. Even if one branch office has sufficient meeting rooms to hold each seminar in a separate room, they would rather hold several seminars in a large room simultaneously. This is intended to increase the interaction between small groups and raise instructors’ competitive awareness. Additionally, each branch office is equipped with desks, chairs, computers, and displays that can be used in small-group seminars. By providing the same equipment at all offices nationwide, they create an environment in which learning can begin immediately, eliminating unnecessary hassles for the Kumon staff. The standardization of hardware and software shows Kumon’s enthusiasm for small-group seminars and the importance of interaction among instructors in the activities of the CoP.

Instructors who wish to participate in small-group seminars can do so by applying to branch offices in their areas. Kumon assigns five or six members who will attend the seminar, some of which are veterans, while others are newcomers. The learning activities are facilitated by staff, and instructors present and discuss their own cases. This allows new instructors to ask questions and expert instructors to get to know the newcomers and train them based on their individual needs.

Small-group seminars have a significant impact on the professional growth of the Kumon staff. Before these seminars were established, the consulting staff had to create their own content, which led to difficulties in ensuring uniformity. By standardizing the content, it became easier to compare different methods of teaching the same content. It became clear how the facilitation of small-group seminars differed among staff members and what they needed to learn. Learning among consulting professionals became more active, and newcomers were able to acquire knowledge and skills more efficiently by observing expert staff seminars. A multilayered CoPs were also been established as a result of joint learning among several offices within an area or the presentation and sharing of best practices at the national level, beyond the boundaries of the office.

The characteristic of small-group seminars is that standardized content is learned by a CoP that emphasizes small-group interaction; however, when compared to seminars that are spontaneously constructed by instructors, it is clear that the two CoPs have different characteristics. Kumon’s system of equipping instructors with teaching skills allows different CoPs to coexist and interact with each other. It is a combination of the two CoPs described below that facilitates learning.

Kumon has several systems that support those who have only been teaching for a short period. One of these is the “Instructor Advisor” system, in which senior instructors mentor first-year instructors. There are events called the mentor seminars that bring together mentoring instructors and instructors involved in the management of the seminar. The unique feature of this event is that the participating instructors are limited to those who are highly successful, not only in their teaching skills but also in classroom management. In other words, these seminars are CoPs for accomplished teachers.

Mentor seminars are held regularly and are led by highly skilled instructors who have worked for many years; their purpose is to improve the skills and management performance of both instructors and the branch office. Many of these highly skilled instructors are well known, not only at the regional level, but also at the area and national levels. The opportunity to meet and hear from such instructors is valuable for those who have attained a certain level of proficiency.

There are three reasons why instructors participate in mentor seminars. The first reason is the same as the incentive to participate in selective training in companies. In other words, participation in a mentor seminar means that one’s teaching skills and classroom management results are recognized by Kumon. The second reason is the opportunity to meet and learn from highly skilled veteran instructors, who are good role models for instructors. This opportunity is both a badge of merit to the instructors for their teaching skills and classroom management efforts and a strong incentive to participate. Third, there is an opportunity to interact with other proficient instructors. As they become more proficient in their teaching skills, some instructors may wish to further develop themselves in a higher-level CoP. However, such opportunities are not easy to access, especially in rural areas, where there are few classrooms. However, mentor seminars, which are CoPs in their own right, make such opportunities more accessible since they facilitate interactions with instructors of certain proficiency levels. Further, they provide a platform on which networks among proficient instructors can expand, which can then be filtered down to seminars and small-group seminars.

The mentor seminar that the author observed was attended by approximately 200 of the most proficient instructors in the area. After the opening greeting, there was an opportunity to ask participants to present recent examples of their work achievements. Presenters had been pre-selected, and perceived as honors. The highly skilled instructors provided feedback on the presentations and praised the presenters’ efforts and ingenuity, and all the participants applauded them. After the presentations, a group discussion of the content of the presentations was held for approximately 20 minutes. Proficient instructors sat near each other at their desks and discussed their case studies and experiences. The instructors were distributed such that they were not clustered with those from nearby offices, allowing for networking among the instructors. Highly proficient and experienced instructors presented discussion topics such as “changing the mindset of instructors,” which evoked lively discussions. Several participants reported on the results of these discussions. Some instructors reported that they realized the high quality of the mentor seminars and the stimulation that came with them. The Kumon staff members also participated and were tasked with helping the instructors that they were in charge to build their networks and inspire them to grow. They asked the mentors to support them in doing so.

During the final question-and-answer period, the high-skilled instructors provided advice on specific issues related to seminar management one after another from the perspective of Kumon’s local-level long-term development plans. Thereafter, some of the instructors expressed the significance of participating in these seminars to me, explaining that in their area, there are no other proficient instructors, hindering their ability to learn together. They expressed that meeting and hearing the highly skilled instructors motivated them.

Instructors’ research conferences are Kumon’s largest CoPs as they gather instructors from all over Japan at a large venue once a year to present and share research results.

At the conference that the author observed, at first, breakout sessions were conducted to present teaching methods. Divided by subject and purpose, instructors presented effective teaching methods that have been studied in seminars. As only highly successful teaching methods that have passed the screening process can be presented at such conferences, these presentations and the methods taught therein were important for the instructors to grasp. Some instructors aimed for seminars where they hosted presentations and sought to develop their abilities and confidence by recruiting younger instructors.

The presentations we observed concerned teaching methods for Japanese language materials and learners, who explained the areas with which students tended to struggle, methods that had been effective in helping them overcome these obstacles, and ways to use existing methods to solve specific problems with the materials. Instructors listened attentively and took notes on the teaching methods.

In another room, there was a breakout session in which instructors with short teaching careers and senior instructors met and presented their experiences. The presenters explained how they overcame specific problems and concerns, such as how they established their classrooms and balanced their family lives in the early years of their careers. Afterward, there was time for the instructors to interact with each other. Communication between instructors with short careers allowed them to share their concerns. The new instructors listened attentively to the seniors’ experiences. Because new instructors who have just opened their own classrooms typically do not have many opportunities to network with other instructors, it is very important to provide forums such as these for them.

After the seminar, a plenary session was held in a large hall, where all the participating instructors gathered. During the plenary session, Kumon explained its history and future strategies, and awarded instructors with long careers. The instructors aspired to receive such awards in the future, so they listened attentively to the veteran instructors’ award speeches. The subsequent reception was said to be an opportunity for networking among the instructors.

In summary, these instructors’ research conferences are CoPs open to all instructors. These are platforms for presenting and sharing teaching methods. By bringing together diverse groups of instructors, the conferences provide exposure to various perspectives. In addition, the conferences are CoPs that promote networking beyond the boundaries of districts, areas, and seminars. Even if the conferences are held only once a year, this networking provides opportunities to participate in new seminars and independent study groups, further promoting learning within the district or area.

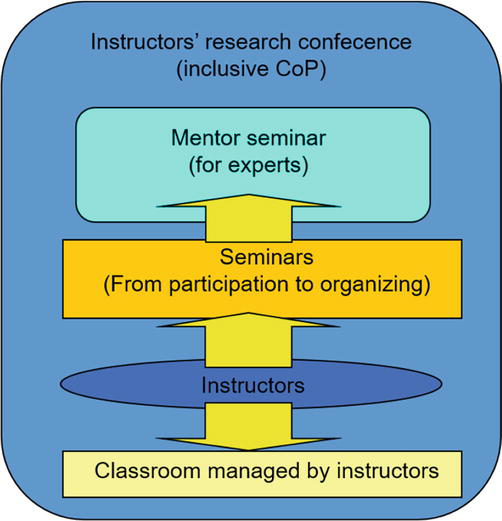

The multilayered structure of the CoPs addressed in this study is summarized in Figure 1.

Layered structure of CoPs in Kumon.

Based on the above examples, the next section discusses the relationship between the structure of CoPs and learning styles, as well as the interaction between CoPs.

We classified the Kumon CoPs in the case studies according to the dimensions of their characteristics, which differ in terms of size, frequency of meetings, and learning activities. The results are presented in Table 3 below.

| CoPs/dimension | Seminar | Small-group seminar | Mentor seminar | Instructors’ research conference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning activity and purpose | Discussion and consultation among instructors, presentation of case studies | Discussions among instructors, advice to newcomers | Discussions and networking among skilled instructors | Research presentations and viewing, interaction with other instructors |

| Scale | Small (20–30 people) | Small (5–6 persons) | Medium (about 200 people) | Large (about 3000 people) |

| Life span | Long (no expiration date) | Short (3 months) | Temporary | Temporary |

| Frequency | Frequent (1 per week to 1 per month) | Frequent (once a month) | About once a year | Once a year |

| Homogeneity | Homogeneous | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous |

| Boundary crossing | Within the boundaries | Within the boundaries | Cross-boundary | Cross-boundary |

| Spontaneity | Spontaneous | Intentional | Spontaneous | Intentional |

| Institutionalization | Freedom | Institutionalized | Freedom | Institutionalized |

| Connection | Horizontal | Horizontal | Vertical | Vertical |

| Learning style | Legitimate peripheral participation Circular learning multifaceted learning | Legitimate peripheral participation Circular learning | Boundary-crossing learning multifaceted learning | Boundary-crossing learning multifaceted learning |

Four CoPs in Kumon.

The first classification characteristic is the frequency of meetings. Seminars and small-group seminars were classified as “interaction CoPs,” in which participants gather frequently for study, while mentor seminars and instructors’ research conferences were classified as “networking CoPs,” held approximately once a year. The next dimension relates to the purpose of learning activities. Although the main purpose of all CoPs is learning and development, the seminars and small-group seminars are interactional, the main purpose of which is to discuss and develop teaching methods with a certain number of members, whereas mentor seminars and instructors’ research conferences are based on exchange, in which the main purpose is to promote human exchange and learning. Mentor seminars and instructors’ research conferences are networking-based events, of which the promotion of human communication is an important objective, in addition to learning. Thus, the four CoPs examined in this study can be classified into two main types: instruction and networking CoPs.

Concerning learning styles, seminars and small-group seminars, which were categorized as instructional CoPs, were conducted to improve teaching skills based on legitimate peripheral participation. Seminars are the lowest-level platform for new instructors and beginners to deepen their participation in the community by presenting and discussing examples from their classrooms. Eventually, accomplished instructors will be able to guide them as successors and help them become accomplished instructors themselves through these seminars and workshops. The frequency of these activities promotes circular learning; that is, the strength of seminars and small-group seminars is that participants practice what they have learned in their classrooms and present the results to the CoP for further discussion. Multifaceted learning is also characteristic of these activities as evidenced by the participants comparing the seminars/independent studies with the methods used in classrooms and manuals.

However, in the case of mentor seminars and instructors’ research conferences, which are categorized as networking CoPs, legitimate peripheral participation is unlikely to occur because they are held irregularly and infrequently. Furthermore, because of this infrequency (being held far apart), frequent circular learning is unlikely. Instead, mentor seminars and instructor research conferences enable boundary-crossing learning outside the community through various encounters. At mentor seminars, networks of high-achieving, high-level mentors are established at once, and at instructors’ research conferences, broad networks of mentors interested in teaching methods and exchange meetings for newcomers are created, from which knowledge and skills are acquired. Participation in these networks promotes multifaceted learning by comparing oneself and one’s skills from various perspectives (from newcomers to veterans, and from seasoned instructors to novices) and learning from the differences.

In summary, we have classified these CoPs into instructional CoPs, in which legitimate peripheral participation and circular learning are the main learning styles and proficiency is achieved through regular learning activities; and networking CoPs, in which boundary-crossing learning is the main learning style. Compared to instructional CoPs, networking CoPs are less effective in deepening skills and knowledge through continuous interactions. Instead, networking CoPs can create an environment that leads to the formation and participation of new CoPs, increasing the potential total amount of knowledge exchanged as well as the knowledge and skills gained through out-of-community learning.

Multifaceted learning occurred for both CoP types. If multifaceted learning is divided into (1) acquiring diverse knowledge and perspectives and (2) learning by finding differences through comparison, it can be said that (1) interaction and (2) networking CoPs are effective for promoting learning. Membership in both types of CoPs (multimembership between the two) leads to further multifaceted learning. Thus, the two types of CoPs are complementary and promote the four types of learning.

Next, we discuss the interactions between CoPs. The CoPs of Kumon instructors that we examined in this study have a multilayered structure. Thus here, we ask the question “What effect does a multilayered structure rather than parallel CoPs have on learning, as in the case of Kumon?” From the learning perspective, we found that the advantages that can be derived from the multiple affiliations of CoPs include the possibility of higher-level learning through multifaceted and circular learning and the ability to build networks among the CoPs. In addition, the case study suggests that the concept of multilayeredness takes two forms: (1) multilayeredness encompassing multiple CoPs, such as the relationship between instructors’ research conferences (national) and seminars (local), and (2) multilayeredness according to the level of proficiency in elementary, junior high, and high schools. The Kumon case is characterized by the inclusion of these two layers within its structure. In other words, from the instructor’s perspective, there is a multilayered structure according to proficiency that consists of the seminars and voluntary institutes that they participate in or host, the mentor seminars where those proficient in these seminars gather, and the national instructor’s research conferences.

This multilayered structure enables instructors, who are learners in this case, to choose CoPs according to their proficiency level. In this case, after becoming proficient, the instructor learners graduate from being participants to being organizers and then to being participants in mentor seminars where other proficient learners can discuss and stimulate each other. Likewise, an inclusive CoP (i.e., instructors’ research conferences) in which anyone can participate and interact with many people makes it possible to build a boundary-crossing network and learn. The multilayered structure of CoPs facilitates learning across community boundaries and the resettlement of communities according to their level of proficiency.

This chapter presents a case study through which we examined the impact of CoPs on learning. We found that the four types of learning in CoPs are achieved through participation in two types of CoPs—instructional and networking—and that a multilayered structure based on the dual multilayeredness of proficiency and inclusiveness promotes proficiency and network building. The following is a description of the theoretical contributions, practical implications, and limitations of this study and its results.

The first theoretical contribution is the derivation of the two types of CoPs based on their characteristics and learning activities. Second, this study relates these CoP types to learning style. The four learning styles proposed in this study were derived from the interaction between the two types of CoPs, which is a result of learners establishing and becoming members of these two types of CoPs. Third, it highlights the significance of the multilayered nature of CoPs based on proficiency levels. Existing studies (e.g., [4]) on global CoPs have focused on the function of inclusion and links between subordinate communities; however, in this study, learners also moved to higher communities in accordance with their proficiency levels. The dual multilayeredness of proficiency and inclusivity facilitates learning across the boundaries of CoPs in two ways: network expansion and movement between communities according to proficiency level. It facilitates learning activities not only between CoPs but also between organizations and CoPs, and the layered structure of CoPs according to proficiency is more effective in building many CoPs within a company and involving organizational members [2, 4]. Therefore, constructing a multilayered CoP structure that promotes boundary-crossing learning between formal organizations can provide a useful perspective on organizational learning.

The first practical implication is the significance of establishing and being a member of these two types of CoPs. By belonging to either the interaction type or the networking type, or both, it is possible to avoid the stagnation of learning, such as ending up in informal gatherings or not becoming proficient, even though exchanges are expanding. Establishing inclusive CoPs is beneficial beyond connections between CoPs. Secondly, we recommend establishing a multilayered structure for CoPs. Although linking different CoPs is important in itself, the formation of an inclusive community that encompasses multiple communities, and an inclusive community based on proficiency, can promote boundary-crossing learning between communities and motivate participants to become more proficient.

Regarding the study limitations, we first acknowledge its limited validity as a single case study. Although the case study presented in this chapter is suggestive and contributes to single case studies, it is important to verify its implications with other case studies, quantitative studies, and so on. Further research and comparative studies of these CoPs are required.

Submitted: 23 August 2023 Reviewed: 04 September 2023 Published: 06 October 2023

© The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.