Abstract

In December 2022, protests began in Israel against proposals to reform the country’s legal system. Some maintained this was a legal reform, while others contended it was a regime coup. Using multimodal discourse analysis, we analyzed 162 protest signs displayed during the 20 weeks of demonstrations from January 2023 through May 2023. We organized the evolution of the signs according to Lewis and Reese’s three stages of communication: transmission, reification, and naturalization. For instance, the slogans that initially talked about a legal revolution (transmission) later changed to charges about attacks on democracy (reification) and, finally, a regime coup (naturalization). Findings show three main characteristics of the slogans: (1) focus on values such as the importance of democracy, (2) the expression of individual, subgroup and collective forms of protest, and (3) appeals to the international community to pressure the Prime Minister and the government. The findings also confirm the usefulness of Lewis and Reese’s model, originally designed to analyze journalism articles, in assessing the text and visuals of protest slogans.

Keywords

- social activism

- protest signs

- slogan

- legal reform

- regime coup

1. Introduction

Political, social and ideological issues in the public discourse, often displayed using slogans on protest signs, mutually shape each other [1]. ‘Historically, images of social movements have helped to capture the power and potential of contentious policies in changing laws, overthrowing regimes and fighting perceived injustices’ [2]. Researchers have noted that analyzing slogans provides insights into how political and social issues are presented to the general public. The choice of the text for the slogans and the protest signs is important in helping the general public understand the agenda of the protest and encouraging their attendance at demonstrations [3]. Social groups need visibility for their protests to succeed. In addition, the text and visuals of the demonstrators and the protest slogans convey the protesters’ message to the general public and the authorities [3, 4].

Van de Velde [5] contended that the demonstrators’ posters, signs, clothes and words are key elements for social groups, individually and collectively. All protest writing is a public expression whose visual power conveys a political message expressed in the written word. The slogans and text on the protest signs are becoming increasingly more personal. Nevertheless, they are designed to promote the collective agenda of the protest and, at the same time, directed at the general, local and global audience.

McGee [4] pointed out that political slogans are effective tools for persuasion, the expression of political goals, and a means of raising political consciousness and organizing a set of cultural attitudes. Slogans are also a form of “controlling consciousness.” In his paper, “The ‘Ideograph’: A link between rhetoric and ideology,” McGee [4] focused on the concept of “ideology.” He maintained that slogans contain a vocabulary of “ideographs” depicting a society’s political consciousness.

2. Literature review

2.1 Signs as a tool for mobilization

“Condensing symbols are verbal or visual images that neatly capture—cognitively and emotionally—a range of meanings and convey a frame, master frame, or theme. Organizers use such symbols to recruit members, especially those with different agenda. A powerful symbol lends credibility to an explicit argument by connoting the implicit assumptions embedded in worldviews and common sense” [6]. Protest signs are a visual form of communication used to express dissent, raise awareness, and mobilize people to take action. They are often used in conjunction with other forms of protest, such as marches, rallies, and boycotts. According to Kasanga [7], protest signs are not simply a means of communication but also a way of identifying social actors, creating frames of identity, and engaging in intertextuality and interdiscursivity. Such signs are often characterized by the use of slogans, catchphrases and images. They often draw on various sources, including popular culture, history and religion. Protest signs can represent people as members of groups or assign them particular roles. For example, a protest sign that says “Black Lives Matter” constructs Black people as a group facing discrimination. Similarly, a slogan that says, “We are the 99%,” creates a frame of identity that pits the 99% of people struggling against the 1% who are wealthy and powerful [5]. Bahrudin, Bakar [3] also found that slogans are important for expressing a group’s social and political ideology. The group uses them to begin the proactive process of conveying messages through the slogans via visual representations. This process happens in intertextual protest discourse.

2.2 Social movements’ collective identity: Us vs. them

Social groups are a union and connection of individuals with the desire to bring about change [8, 9, 10]. Demonstrations are the main form of communication between the groups and their target audience [11]. McAdam et al. [10] refer to demonstrations as manifestations of “social change processes.”

Designing a collective identity is a cultural process expressed in language and symbols. The sources of communication are a necessary condition for the success of this process [12]. The rapid growth of social networking sites demands reconsidering the meaning of mediated political participation in society [13]. In the past, the collective identity was shaped by the media coverage of social groups. Given that language and symbols are part of the culture of the reading public, this coverage connected the reading public to the agenda of the social group. Commenting on the politics of identity, Melucci [14, 15, 16] argue that identity is not limited to knowing the members of the group by their self-identity. It also depends on others recognizing their unique identity and receiving societal legitimacy. Collective identity is a shared, interactive definition produced by several individuals (or groups at a more complex level). It involves actions and the opportunities and constraints in which they occur [15, 16]. Through this process, a community creates its identity.

Groups share common interests arising from the experiences and solidarity of their members [17]. Defining their identity results in identifying the social actors by themselves and by others as part of a wider group. Through this sharing, they give meaning to their experience [18]. Furthermore, slogans describe the identities on which the movements are based. They indicate the relationship between “I,” “us” and “them.” They also distinguish between the characteristics and goals of those affiliated with them and those opposed to them [16]. However, the “we” aggregate into a pool of individuals rather than a potential collective actor [16].

2.3 Protest writing as political performance: Telling the public who “I am” and “we are”

The role of slogans is to inform the general public of social and ideological reality and influence the shaping of that reality. Sharp [19] notes the ability of slogans to influence and motivate people to participate in protest actions to protect their position in society or their interests [3]. Barton [20] demonstrates that slogans communicate ideas and create a feeling of solidarity among the participants in the demonstrations designed to promote the group’s interests [3].

Protest slogans and signs have an expressive strength that conveys messages about rational and emotional dimensions. Beatrice Frankel (cited in [5]) describes public slogans as an “act of writing and language” that combines personal and group concerns. Van de Velde [5] describes them as a “political spectacle”, demonstrating the individual’s place in the signs through the slogans ‘Je suis Charlie’, ‘Me too’, and ‘I cannot breathe’. The individual’s protest uses public words that the audience can understand and identify with because they come from their personal experience in the social situation. As a result of the increase in the place of the individual within the collective, a distinction is made between individual and collective writing. The collective message can be seen in the use of words representing a collective such as “we” and “us.” This expression corresponds to conduct on social networks that strengthens the “me” in public concerns.

Indeed, in the view of Castells [21], protest writings are characterized by increased media awareness and the potential to spread messages beyond the crowd of protesters participating in the event. Variations in the potential audiences prompt the use of visual images to ensure that they can speak to all of these audiences. In other words, protest writings will often appear not only as words but also combined with images and inscriptions on the protesters’ shirts that convey the atmosphere on the street. The reverse process also happens: the collective voices amplify the individual’s voice. Therefore, we should not regard the protesters as a homogenous bloc but as various voices present at the event. This point is important because sometimes the protest writings are the ones that convey the protesters’ claims that are beyond the claims that are presented or framed by the media. Therefore, the multiplicity of meanings must be considered to examine the messages the demonstrators convey that are beyond the group’s agenda.

Utilizing this broader perspective helps us move away from the image of the homogeneity of the protest [5]. van Stekelenburg, Klandermans [22] indicate that protest writings are rich expressions of the collective identities of the demonstrators as well as the emotions expressed publicly in these movements. Thus, protest actions convey individual or collective feelings implicitly or explicitly. Through them, the participants can express anger, hope or any other emotion associated with the movement’s central message [5, 23].

The claims made on the protest signs refer to the complaints and the individual and collective experiences of those who share the sense of injustice that led to the protest. The individual words provide a window into the basis of the social protests [5]. The demonstrations include group posters, individual posters, handwritten or printed signs, and words written on walls. Other forms of protest include songs and [24] videos on social media that allow multimodal storytelling [25, 26]. Posting personal information, photos and images related to the demonstrations created a new cultural language and style [27, 28, 29, 30]. Hence, signaling that one is concerned about social issues through such online postings is one of the ways of indicating the power dynamics in the discourse. Understanding the inclusion and exclusion of social actors in constructing the protest signs’ messages reveals the power relations, hidden values and ideology of those involved in the protests (Syuhada et al., 2021 cited in [3]).

2.4 Typologies for analyzing slogans

There is extensive research on the effect of language on audiences (e.g., [4, 31]). One of the studies that provide a model for investigating the forms of communication of protest signs is that of Lewis and Reese [32]. This model was originally intended to analyze journalism articles. Their model identifies three factors that can be used to indicate how social groups consciously choose to express their protest and the evolution of the messages it conveys. The three factors are transmission, reification and naturalization.

The transmission stage is the most complex because it determines the narrative on which the discourse will be based. This is the most basic step for the next two components. The reification stage turns the agenda of the protest into an accepted tangible fact in the form of a social demonstration. In the reification phase, the text is written in the language the group has already accepted. The assumption is that the narrative will be translated into reality. This action becomes routine. At this stage, there is no criticism of the constructed narrative. In other words, the terms and phrases already decided upon in building the initial narrative have been accepted. All that remains is to translate them into actions. Naturalization is the act of assimilating information into long-term mental and emotional memory and linking it to additional internalized data. The act of internalization can be conscious or unconscious. According to Lewis and Reese [32] naturalization transforms the selected narrative into a new reality.

The second model is that of van De Velde [5], who identified four typologies for analyzing the forms of communication of protest signs: demands, proclamations, mobilization and bearing witness.

Demand involves political claims or expressions of opposition to policies addressed directly to government institutions. The messages are communicated visually to convey them to the collective. They are usually in a short, blunt format, whether carried by individuals or groups. The messages are written in a clear (reporting), effective (illustration) and agreed-upon (internalization) manner. Whether they are carried by groups or individuals, in Lewis and Reese’s [32] terms, they are marked by the imperatives of clarity [transmission], efficiency [reification] and consensus [naturalization].

Proclamations are elaborate, controversial arguments designed to appeal to the general public. Even if the message of the demonstration is clear, the signs take the form of political slogans illustrating the desired political solution after the narrative against the government has been absorbed. Individuality is reflected in the creativity of the slogan writers and in the personal adaptation of the message to strengthen and diversify it.

Mobilization refers to the goal of recruiting demonstrators to strengthen the impact of the message. The messages are addressed to the internal public of the protest, encouraging them to participate. These messages are shaped by the collective that organized the protest to transmit a message of solidarity. In this way, they are also a means of recruiting audiences from outside to join the protest.

Finally, these messages may evoke empathy, words of support, and personal testimonies gathered together under a hashtag on social media networks. This process allows even those who do not demonstrate personally to bear witness to their agreement with the sentiments of the protests.

According to Van De Velde [5], collecting and analyzing protest signs has methodological and ethical challenges. This task, she notes, requires a great deal of thought on the researcher’s part about how data are collected or sampled. One method of doing so is using “netnograghy,” a technique that includes gathering photos of slogans from press sites, private blogs and social media. In addition, Van De Velde [5] states that protest writings are traces of social movements and must be placed in their temporal and geographical contexts. Slogans change from protest to protest. They may also evolve in light of changes in the protesters’ demands, the power relations with the government or the police. For example, if the police use force to suppress the protests, the protesters’ slogans might change.

Using these models of Lewis and Reese [32] and Van de Velde [5], we can examine the widespread demonstrations that began in Israel in January 2023 against proposals to change certain aspects of the judicial system and the method of electing judges to the Supreme Court.

3. Method

3.1 Testing the typologies using Israel’s demonstrations against judicial reform

The protests began in January 7, 2023 with the publication of the Levin reform, which the protestors called a “legal revolution.” They regarded it an attempted coup d’état that would harm Israeli democracy and the balance between the three branches of government. They contended that passage of the legislation would weaken the legal system and give unlimited power to the executive and legislative branches. In February 2023, the protest demonstrations spread to approximately 150 centers in Israel. The weekly number of demonstrators throughout Israel reached hundreds of thousands in April. At the same time, weekly demonstrations began throughout Europe and the United States.

3.2 Data collection

McGarrey et al. [2] note that social movement research has overwhelmingly privileged text over images, resulting in researchers failing to consider the visual components of protests. Thus, there is limited research on how protesters use images, how images capture and communicate moments of struggle, and how images produce shared meanings of contentious politics.

With this consideration in mind, every week from January 2023 through May 2023, we tracked and collected the photos published on social networks that were taken by photographers at the demonstrations in order to document the evolution of the social protest and the changing demands of and the power relations with the government. In total, 162 images were collected and analyzed during this time period. Note that the photographers’ copyrights were strictly protected.

3.3 Data analysis

After saving the images and creating a database according to the dates and places of the collection, each sign was analyzed according to the characteristics of the medium, writing style (printed or handwritten), images and the context in which they were written and whether the message was from an individual or a group. Following Van De Velde’s [5] recommendation, attention was paid to the text’s combination of slang, humor, puns, and social and cultural references.

We conducted a multimodal discourse analysis whereby meaning is determined using multiple means and elements of communication, such as text and images that, combined, create new content [26, 33, 34]. We then classified the results into the three stages in Lewis and Reese’s [32] model.

4. Findings

4.1 The first stage: Transmission

According to Lewis and Reese’s [32] model, transmission is the first stage. It is during this stage that the narrative is created. What is the idea behind the legal reform and the warnings against it? Based on the analysis, the transmission phase covered January 7 to January 27.

The choice of the text for the slogan and the protest signs is important for helping the general public understand the agenda of the protest and mobilizing them to participate in the demonstrations [3].

At this stage, signs such as

Additionally, the narrative included threats such as

The slogans also underscored the legitimacy of demonstrating and protesting against the authorities—

Even at this stage, one subgroup emerged from the larger group of demonstrators: those involved in high-tech. As Israel’s reputation as a startup nation implies, those who work in high-tech are regarded as the superstars of the Israeli economy. Thus, their slogans underscored their contribution to the Israeli economy and their place within Israeli society:

Figure 1.

Brothers (and sisters) in arms (photo: Idan Golko).

Furthermore, these slogans describe the identities on which the movements are based, especially the distinctions between “I” and “us” and “them.” They provide a better understanding of political affiliation and the individuals and goals that the movement opposes [16].

In the context of democracy, Della Porta and Diani [8] note that social action is driven largely by the fundamental principles with which actors identify. According to this perspective, “values will influence how actors define specific goals and identify strategies which are both efficient and morally accepted” [18]. Thus, slogans such as

Figure 2.

Save our startup nation (photo: Shaul Golan).

4.2 The second stage: Reification

The second stage of reification began in mid-February and lasted until March 25. During that time, the slogans emphasized the consequences of the passage of the reform. For example,

In addition, to convey a message directed to the global community [5], the demonstrators unfurled a large sign made of fabric with an image and text that could be seen only from the air by a drone:

During this phase, there were also signs with individual sentiments that indicated anger. One said

During this period, another subgroup appeared, a group of lawyers who stood together wearing the suits and robes they would wear in court. Their sign was an appeal claiming that

One other expression of individualism is the presence of handwritten signs. They conveyed personal statements such as a girl holding a sign that said “

In this case, the message is that the demonstration comprises many individuals. As a protest that conveys individual or collective feelings, whether implicitly or explicitly, it allows one to express anger, hope or any other emotion associated with the movement’s central message [5, 23] and the shared definition produced by several individuals [15].

Another sign, “

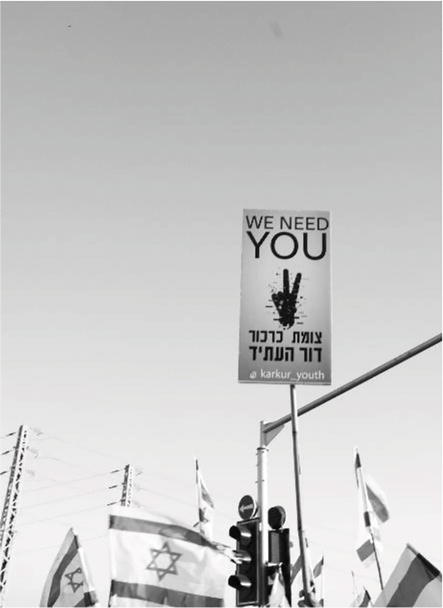

Figure 3.

We need you (photo: Idan Golko).

Thus, texts and images such as the phrase “

4.3 The third stage: Naturalization

The last stage, naturalization, was also the longest, extending from March 25 to May 31. Most of the messages in the naturalization stage reflect that the public has already internalized the message about the legal reform’s consequences.

At this point, the signs said:

The collective message is evident in using words representing a collective such as “we” and “us.” The concerns are concerns about the collective. Two slogans that appeared at this time referenced lines from a well-known Israeli song:

During this stage, there were also messages to the international community to pressure the Prime Minister to stop the legal reform. Therefore, some of the signs were in English. Indeed, many more than appeared during the initial stage. Examples include Israel [with a picture of its flag]

On May 29, 2023, a picture was taken via drone showing a huge sign made of fabric carried above all of the demonstrators saying,

Figure 4.

Never surrender (drone photo: Or Hadar).

At this point, the subgroup of high-tech workers that emerged in the first stage also created a slogan in English, clearly directed at groups outside Israel:

Even at this stage, the individual was visible, as in a handwritten sign that was carried higher than the flags and said, “

Moreover, what most represents the naturalization stage is a sign with a large exclamation point (photo: Idan Golko). At all stages and throughout the demonstrations, there was one consistent sign—“

5. Discussion

Based on the three stages of Lewis and Reese [32] transmission, reification and naturalization—we can see the evolution of the agenda setting in the protests. What began as a protest against a legal reform morphed into a debate about attempts at regime change and a coup d’état. The differences in the protesters’ signs in the three stages mark this transition. For example, in the stage of building the narrative, transmission, the sign ‘Save democracy’ appeared. In the second stage, reification, the sentiment changed to ‘To be free in our country.’ In the last stage, naturalization, the sentiment became more combative: We will not compromise, and we will not give up! We will only allow 100% democracy!.

The words on the signs indicate the power of language to express the ideas created in the narrative in the first stage. There is a connection between words and their meaning because language is how we see ourselves and the world [16].

The transition between the stages was also evident in the choice of images on the signs. For example, in the narrative stage, there was a sign with the words, ‘To be free in our country,’ a reference to a line in Israel’s national anthem. However, in the reification stage, there was a picture of a woman holding an image of two of her daughters with their heads in a cage (photo: Idan Golko). The implication was their lack of freedom in the future if the coup d’état took place.

In addition, in the reification stage, some of the signs calling for the preservation of democracy added the image of a fist taken from other demonstrations around the world. Adding elements associated with a certain movement and more universal images used by several movements helps those outside the country understand and identify with the demonstrators’ goals [16]. The arm raised with a clenched fist is a familiar symbol from protests worldwide. However, it is an image with a built-in contradiction. On the one hand, it represents “positive” values such as solidarity and shared destiny. On the other hand, it is difficult to ignore its implied threat and its association with the violence that has accompanied groups such as Black Lives Matter that have used it.

The text and images on the protest signs have three main characteristics. First, they focus on values. In all three stages, most protest signs underscored the importance of democracy as a fundamental value in Israel and the negative consequences of its loss as a reason to fight to uphold it.

The second characteristic is the expression of the “us” in both its individual and collective form. Using first-person pronouns allows individual agency in voicing dissent and prompts us to look beyond the unity and solidarity of the protesters and understand that they are not a homogenous bloc. While in most of the research literature [3, 5, 8, 9, 10], it seems that there is a place for the individual within the group and the group as a collective, in the case of Israel, the social group that demonstrated against the legal revolution included the characteristics of the social groups affected by the demonstrations against economic globalization in which distinct subgroups were seen within the larger protest group. In Israel, the subgroups included some of the most influential members of Israeli society, those involved in its economy (owners of high-tech companies) and its security (pilots and fighters).

The third characteristic is the appeal to the international community. In all three stages of the protest, there were signs in English designed to prompt the international community to help the protesters and to pressure the Prime Minister and the government not to pass the legal reform. Indeed, their signs had the desired effect. When the Prime Minister and other government officials arrived for meetings with politicians worldwide, they were met by demonstrators who carried signs identical to those in the demonstrations in Israel. In addition, to align the protest with those in other countries, the signs displayed images associated with demonstrations in other countries that would be easily recognized. Examples include signs with the raised hand and clenched fists and women wearing red robes and white bonnets associated with the series ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ as a symbol of violence against women (photo: Amir Tirkel) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Bonot alternativa (building an alternative) ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ representation.

Contemporary social movements are subject to viral diffusion. As researchers have noted, the phenomenon can be observed in the instant spread of slogans, messages and images urging action [21]. Users of social media sometimes adopt these images as their profile pictures. Today, social media platforms play a significant role in identity construction among members and sympathizers of social movements. Indeed, they have become the sites where new names, symbols or slogans are created and diffused, thus fostering collective identity [38].

Future research may consider the content analysis of protest signs, stickers and signs in the public space, clothing, and other methods that social groups use to disseminate their messages, encourage people to join their protests and make their cause accessible to broader audiences. With the right verbal resources, protest signs can be an effective medium for spreading ideologies and negotiating a balance of power in enacting social changes between the citizens and the government.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to Mrs. Diane Romm for her valuable insights as well as for editing the chapter content.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Mrs. Ariane Cukierkorn, Information Specialist, for her helpful and constructive comments and for her help in editing the manuscript.

Thanks to the Research Committee of Zefat Academic College for the grant.

References

- 1.

Condit CM, Lucaites JL. Crafting Equality: America’s Anglo-African Word. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993 - 2.

McGarry A, Jenzen O, Eslen-Ziya H, Erhart I, Korkut U. Beyond the iconic protest images: The performance of ‘everyday life’ on social media during Gezi Park. Social Movement Studies. 2019; 18 (3):284-304. DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1561259 - 3.

Bahrudin H, Bakar KA. Us vs. them: Representation of social actors in women’s march MY protest signs. Journal of language and linguistic. Studies. 2022; 18 (S1):313-329 - 4.

McGee MC. The “ideograph”: A link between rhetoric and ideology. Quarterly Journal of Speech. 2009; 66 (1):1-16. DOI: 10.1080/00335638009383499 - 5.

van de Velde C. The power of slogans: Using protest writings in social movement research. Social Movement Studies. 2022:1-20. DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2022.2084065 - 6.

Jasper JM, Poulsen JD. Recruiting strangers and friends: Moral shocks and social networks in animal rights and anti-nuclear protests. Social Problems. 1995; 42 (4):493-512 - 7.

Kasanga LA. Semiotic landscape, code choice and exclusion. In: Conflict, Exclusion and Dissent in the Linguistic Landscape. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. pp. 123-144 - 8.

Della, Porta D, Diani M. Social Movements: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009 - 9.

Tilly C. Political identities in changing polities. Social Research: An International Quarterly. 2015; 70 (2):605-619 - 10.

McAdam D, Tarrow S, Tilly C. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001 - 11.

DeLuca KM, Lawson S, Sun Y. Occupy Wall street on the public screens of social media: The many framings of the birth of a protest movement. Communication, Culture & Critique. 2012; 5 (4):483-509 - 12.

Berenson A. Journalism and social media frame social movements: The transition to media matrix. In: Višňovský J, Radošinská J, editors. Social Media and Journalism: Trends, Connections, Implications. London: IntechOpen; 2018. pp. 67-83 - 13.

Fenton N, Barassi V. Alternative media and social networking sites: The politics of individuation and political participation. The Communication Review. 2011; 14 (3):179-196. DOI: 10.1080/10714421.2011.597245 - 14.

Melucci A. The process of collective identity. In: Johnston H, Klandermans B, editors. Social Movements and Culture Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1995. pp. 41-63 - 15.

Melucci A, Keane J, Mier P. Nomads of the Present : Social Movements and Individual Needs in Contemporary Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1989 - 16.

Chodak J. Symbols, slogans and taste in tactics: Creation of collective identity in social movements. In: Volodymyr Y, Wysocki A, Kisla G, Jekaterynczuk A, editors. Identities of Central-Eastern European Nations. Kiev: Interservice; 2016. pp. 277-297 - 17.

Taylor V, Whittier N. Collective identity in social movement communities: Lesbian feminist mobilization. In: Morris AD, Mueller CM, editors. Frontiers in Social Movement Theory. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1992. pp. 104-129 - 18.

Diani M, Della PD. Social Movements: An Introduction. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999 - 19.

Sharp HS. Advertising Slogans of America. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press; 1984 - 20.

Barton EL. Informational and interactional functions of slogans and sayings in the discourse of a support group. Discourse & Society. 1999; 10 (4):461-486 - 21.

Castells M. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2015 - 22.

van Stekelenburg J, Klandermans B. Individuals in Movements: A Social Psychology of Contention. Handbook of Social Movements across Disciplines. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 103-139 - 23.

van de Velde Cc. The “indignados”: The reasons for outrage. Cités. 2011; 47-48 (3):283. DOI: 10.3917/cite.047.0283 - 24.

Riessman CK, Sage P. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; 2008 - 25.

Davidjants J, Tiidenberg K. Activist memory narration on social media: Armenian genocide on instagram. New Media & Society. 2021:1-16. DOI: 10.1177/146144482198963 - 26.

Jones RH, Chik A, Hafner CA. Discourse and Digital Practices: Doing Discourse Analysis in the Digital Age. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2015 - 27.

Calderón CA, López M, Peña J. The conditional indirect effect of performance expectancy in the use of Facebook, Google+, Instagram and twitter by youngsters. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. 2017; 72 :590-607 - 28.

Cheng L. Do I mean what I say and say what I mean? A cross cultural approach to the use of emoticons & emojis in CMC messages. Fonseca. 2017; 15 :199-217 - 29.

Lou J, Jaworski A. Itineraries of protest signage : Semiotic landscape and the mythologizing of the Hong Kong umbrella movement. Journal of Language and Politics. 2016; 15 (5):609-642. DOI: 10.1075/jlp.15.5.06lou - 30.

Lundgren H, Poell RF, Kroon B. “This is not a test”: How do human resource development professionals use personality tests as tools of their professional practice? Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2019; 30 (2):175-196 - 31.

Sonntag SK. The Local Politics of Global English : Case Studies in Linguistic Globalization. Lanham, Md: Lexington Lanham, Md; 2004 - 32.

Lewis SC, Reese SD. What is the war on terror? Framing through the eyes of journalists. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2009; 86 (1):85-102. DOI: 10.1177/107769900908600106 - 33.

Jones RH. Multimodal discourse analysis. In: Chapelle CA, editor. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2021. pp. 1-6 - 34.

Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2008 - 35.

Said SB, Kasanga LA. The discourse of protest: Frames of identity, intertextuality and interdiscursivity. In: Blackwood R, Lanza E, Woldemariam H, Milani TM, editors. Negotiating and Contesting Identities in Linguistic Landscapes. London: Bloomsbury; 2016. pp. 71-83 - 36.

Kasanga LA. The linguistic landscape: Mobile signs, code choice, symbolic meaning and territoriality in the discourse of protest. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2014; 2014 (230):19-44. DOI: 10.1515/ijsl-2014-0025 - 37.

Akhtar A, Aziz S, Almas N. The poetics of pakistani patriarchy: A critical analysis of the protest-signs in women’s march Pakistan 2019. Journal of Feminist Scholarship. 2021; 18 (18):136-153 - 38.

Gerbaudo P, Trere E. In search of the ‘we’ of social media activism: Introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities. Information Communication & Society. 2015; 18 (8):865-871. DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043319