Abstract

Urban farming is a simple concept yet significantly impacts food security and food sovereignty for urban households. Indonesian context defined urban farming as cultivation practices, including food crops, vegetables, fruits, herbs, medicinal and ornamental plants, with some combination of fishes and poultry in urban areas, namely home yard, office yard, school garden, communal garden, and many more. This chapter aims to discuss five main topics related to the urban farming movement in Indonesia: (1) The dynamic of yard utilization and food provision policy; (2) The importance of urban farming in society; (3) Community perception and involvement in urban farming; (4) The impact of the pandemic on household food security and food supply chains; (5) Government strategy to sustain participatory urban farming. The sustainability of urban farming still requires government assistance and intervention, and private involvement through corporate social responsibility. The government must support infrastructure both in terms of policy and physical implementation to facilitate the establishment of a network of business partnerships between producer farmers and various market actors in a market chain to step up the era of urban farming industrialization.

Keywords

- participatory gardening

- home gardening

- community garden

- urban farming

- food security

- food sovereignty

1. Introduction

Food security and sustainable agriculture are among the critical issues and priorities in the planning and development in Indonesia. This is in accordance with the global commitments contained in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to encourage the implementation of sustainable development. One of the 17 the strategy in the SDGs is to end hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition, and proclaimed sustainable agriculture [1].

The increase in the number of urban population marked by urbanization has become a global issue that requires a comprehensive solution because its impact is related to various aspects of development. Some Frequent challenges and problems that appear among them are not balanced numbers, distribution and population composition, declining environmental quality due to reduced open land/green space, and adequate food availability and quality for city dwellers. One solution that needs to be developed to cope with the problem is urban farming.

Urban farming is a subset of urban agriculture that focuses on income-making agricultural activity. It can be either community farms (driven by social aims) or commercial farms (motivated by profit) and hence can be run as nonprofits or for-profits [2]. Another author characterized urban farming succinctly as food production within cities [3]. In Malaysia, urban farming is described as the practice of planting, processing, and distributing agricultural products in cities and adjacent areas [4]. The same definition is applied in the Indonesian context. Likewise, in this review, urban farming is not seen as an industry but as cultivation practice, including food crops, vegetables, fruits, herbs, and medicinal and ornamental plants in urban areas.

The urban farming movement in Indonesia is promoted to achieve food security and food sovereignty. Food sovereignty is defined as “local people’s right to govern their own food systems, including markets, ecological resources, food cultures, and production methodologies.” [5]. Food sovereignty is a continuous process in which required adjustments are sought in order to achieve food security [6, 7, 8]. It goes beyond the emphasis on food security by giving growers authority [9]. Because of the alleged importance of food sovereignty to self-sufficiency and food security, various nations have enacted legislation to protect this right [10]. Indonesia is one of 10 countries whose constitutions have recognized food sovereignty [11].

2. Dynamics of yard utilization and food provision policy

One of the Indonesian Government’s efforts to achieve household food security is to make food available and accessible at the family level by utilizing yard land. Yard utilization offers a solution to anticipate the high rate of rice demand due to population growth through food diversification [12]. The national yard land area is around 10.3 million ha or 14% of the total agricultural land area. If this can be optimally utilized, it will be an enormous potential as one of the providers of nutritious and economically valuable food sources. A yard is a piece of land around the house, whether in front, on the side, or behind the house [13]. The utilization of the home yard is crucial because numerous benefits can be taken. The re-establishment of the yard utilization program in Indonesia with a variety of crop, livestock, and fish commodities is expected to make the food and nutritional needs of household members accessible and affordable.

Through the Ministry of Agriculture, the Government of Indonesia issued various policies related to the importance of food diversification through the optimization of yard land to increase community participation in improving food security and food sovereignty at the household level. Some implemented programs are explained below.

2.1 Sustainable food home area model/model kawasan rumah pangan lestari (MKRPL)

The Sustainable Food Home Area Model (MKRPL) is an implementation of the food security program by the Indonesian Agency for Agricultural Research and Development which was started in 2010. Food security program through optimization of environmentally friendly yard land to meet families’ food and nutritional needs. Through MKRPL, public awareness to provide food for families was sown. It is designated as a pilot project to make the home yard productive. Development of MKRPL throughout Indonesia to support food sovereignty and food diversification by involving community participation in rural and urban areas [14].

The concept of m-KRPL/KRPL development is designed in a concentrated area to facilitate management and assistance and provide economic value for the community because it can produce marketable food products. Meanwhile, the sustainable concept is designed with the development of a Village Seedling Garden or communal nursery (Figure 1) to supply the needs of KRPL members and communities interested in optimizing yard land and supporting the sustainability of activities [12]. The limited land in urban yards can be addressed by cultivation techniques, namely vertical planting designs, pots, and vines with pergolas—a selection of plants that can be consumed by the family (edible plants). The use of household yards is quite effective with the participation of the community in designing the productive yard [15]. However, some urban residentials in big cities have no space yard for gardening, for this case, a communal/community garden can be a solution. The residents are still able to collaborate in maintaining a garden within shared open spaces (Figure 2a and b).

Figure 1.

A communal nursery in Jakarta.

Figure 2.

Collaborative work in communal garden (a) seedling preparation (b) maintaining the plants until harvest time.

The Indonesian Agency for Agricultural Research and Development further developed the KRPL model in 994 regions from 2011 to 2013 throughout Indonesia. The KRPL model by the Central Food Security Agency since 2013 replicates KRPL into P2KP activities in five thousand villages throughout Indonesia. The KRPL program is an effort by the Government through the Ministry of Agriculture to improve food security and family nutrition. The KRPL program is identical to a similar program called the home garden program developed in many countries worldwide. For example, in Bangladesh, home garden programs can improve food security and reduce malnutrition while reducing poverty in rural areas of Bangladesh [16].

The basic principles of KRPL program development are (i) Utilization of environmentally friendly yards designed for food security and independence; (ii) Diversification of food based on local resources; (iii) Conservation of food genetic resources (plants, livestock, fish); (iv) Maintaining its sustainability through village seed gardens; and (v) Increasing income and community welfare [12].

Although KRPL has been successfully implemented in several regions in Indonesia, however, only a small percentage of Indonesian plan their yards as a food function or grow crops that can meet family food [15]. This condition shows that some people still do not realize the importance of the role of the yard in supporting household’s food sovereignty. To optimize the yard utilization, community involvement or people participation needs to be improved, and assistance from relevant agencies for an ongoing basis.

2.2 Sustainable food yard/pekarangan pangan lestari (P2L)

The KRPL program changed its name to the Sustainable Food Yard program in 2020 to expand beneficiaries and use of yard land. The P2L program is conducted to optimize the use of land yard as a source of family food, supporting government programs in handling priority areas for stunting intervention and handling priorities for vulnerable areas of food insecurity, or strengthening food security areas. This activity is conducted through unproductive yards, bare land, vacant land, the land around houses/residential buildings/public facilities, and other environments with clear ownership boundaries, such as dormitories, Islamic boarding schools, flats, houses of worship, and others. The goals and objectives of P2L activities are: (1) To increase the availability, accessibility, and utilization of food for households following the needs of diverse, nutritionally balanced, and safe food (B2SA), (2) To increase household income through the provision of market-oriented food. To achieve these two goals, P2L activities are carried out through an approach to sustainable agriculture development, local wisdom, community engagement, and marketing-oriented [17]. P2L activities help to meet the food needs of families during the current outbreak of COVID-19 [18].

2.3 Sustainable food torch/obor pangan lestari (OPAL)

The Sustainable Food Torch (OPAL) promotes food diversity to fulfill community nutrition through a pilot use of office yard land in 2019. OPAL is a pilot tool for the community in the use of the yard as a source of food and nutrition. This program is conducted within the scope of the Ministry of Agriculture, the Provincial and Regency/City Offices, which organize government affairs in agriculture and/or food to utilize the land around the office area by planting various carbohydrate source commodities, proteins, vitamins, and minerals.

The COVID-19 pandemic has moved the government and the public a lot in increasing the knowledge and skills of urban people about the importance of plant cultivation in urban and suburban areas, to meet the food needs of families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Displaying the model of yard utilization in front of the office complex has attracted visitors and guests to visit and replicate (Figure 3a), and become designated outdoor activity and education for young students (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

OPAL at the office yard (a) display of

As stated by Handoyo et al. [19], community service activities through the introduction of aquaponics technology can make a positive contribution to urban society. Indicators of success include increased community involvement to participate in vegetable farming with catfish to harvest. Furthermore, the community has benefited from the results of catfish cultivation with an aquaponics system in one cycle amid the COVID-19 pandemic conditions [19]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of locations and community participation in agricultural activities increased, this can be seen from the increase in urban people who grow their vegetables on the vacant lands around the yards [20].

One of the supporting technologies for urban farming during the COVID-19 pandemic that has developed in urban communities is

Figure 4.

Integration of catfish breeding and water spinach cultivation in a bucket (

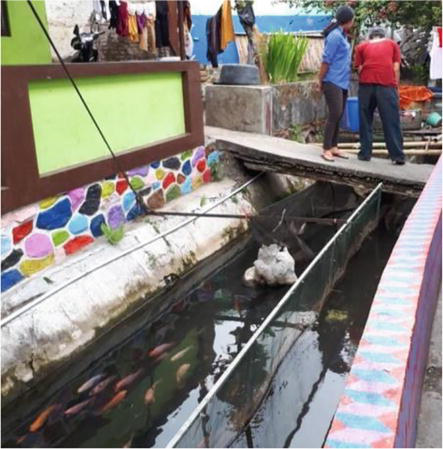

Figure 5.

Tilapia fish breeding in a ditch of housing complex.

3. The importance of urban farming

The importance of urban farming can be viewed from economic, ecological, social, esthetic, educational, and tourism aspects. The benefits of economic aspects include stimulus to strengthen the local economy, increase people’s income and reduce poverty. If the city community is able to meet their own food needs, more of the city people’s money will be used for other interests such as health, education, and housing [22].

When viewed from an ecological aspect, the development of urban agriculture can provide benefits, such as conservation of soil and water resources, improving air quality, creating a healthy microclimate, providing beauty, offers solutions for climate change adaptation.

The social benefits obtained from urban agriculture are increasing food supplies, improving the nutrition of the urban poor, improving public health, reducing unemployment, and reducing social conflicts [22]. Moreover, there is a satisfaction and a pride feeling when we can harvest what we have sown from our yard (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Happy faces during harvest time.

The value of health, education, and tourism is obtained from the presence of increased green open space, more CO2-absorbing areas, improving air quality. Green open spaces become a place to gather, socialize, and recreation and education [23]. For example, in such a big city like Jakarta, the existence of communal garden becomes a place for socializing and spending time for leisure (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Urban farming in Jakarta.

4. Community perception and involvement in urban farming

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic caused many changes in all sectors, and one of them was agriculture. The increase in urban farming enthusiasm in urban communities arises because of working from home and at the same time to survive in large-scale social restrictions implemented in each province and regency/city which narrows the space for movement. With the free time due to work from home and the availability of yard land even though the land is limited, land that was previously less productive can be used as agricultural land to produce household food needs efficiently but healthily [24].

Urban farming is growing along with the increasing interest of people who are influenced by internal conditions requiring activities that can reduce stress and boredom during social restrictions [25]. This urban farming activity is a tool to reduce the negative effects of social isolation due to COVID-19 on a person’s emotions and provide positive benefits for food security and dietary quality by increasing fruit and vegetable intake [12]. Most urban farmers feel positive benefits especially psychological benefits [26]. In the environmental aspect, urban farming activities can reduce urban heat islands and air pollution. Regarding nutrition, urban farming activities can improve the food security of households/communities that are food insecure by meeting their intake needs and reducing costs for vegetables or fresh foodstuffs.

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, it has encouraged urban residents to be more active in agricultural activities. Just like the city community in Yogyakarta formed a passionfruit garden during the COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia. Along with the COVID-19 pandemic, residents became enthusiastic about joining urban farming activities. Agricultural activities in urban areas are a distribution of hobbies and spending free time, where the average urban community are workers and retirees. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced people to stay at home in an effort to stop the widespread spread of the virus, so as to fill the time by cultivating crops, especially vegetables and fruits [27]. The interest of urban people to grow vegetables increased due to the difficulty of the food supply chain, especially from conventional agriculture produced by rural farmers to be marketed in cities. With the use of yard land, community access to food is easier because each sub-district has a vegetable garden that is covered in groups/communities.

The results showed that urban gardening community activity is driven by the desire to reduce household costs, easily get daily food needs, preserve the environment, healthier products, increase income, and fill time free. Urban farming is conducted in various places, such as yards, neighborhoods around houses, and rooftops. To support the principle of reduce, reuse, and recycle (3R) in urban farming, we can make compost in sacks, buckets, drums, used paint buckets, and others. Plants are grown in mineral water bottles, cans, used buckets, pipes, plastic oil packaging, and others [28].

People’s interest in urban farming considers aspects of social, environmental, and economic benefits. One example of an area with a high interest in urban farming is Cirebon City. The cultivation of vegetable crops has been carried out with a verticulture system, both verticulture on a vertical and horizontal household scale which contributes to improving household welfare [29].

The social benefit aspect of urban farming was in the highest rank according to the survey results in Pekanbaru City with a score (3.34) and the lowest score is on economic benefits (2.94). Furthermore, respondents’ interest in continuing urban farming was at high criteria (51.96%) and remarkably high (13.73). Meanwhile, the perception of the community in Gresik Regency is that urban farming has a positive impact on the environment. Most households (80%) state that urban farming is an appropriate effort in environmental management that pays more attention to sustainable agriculture [30].

Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic has begun to slow down, but the conditions felt by the community because of the COVID-19 pandemic are still being felt and are likely to still be felt for a long time, especially in developing countries. According to Roubík et al. [31] the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the poor and other marginalized groups, especially those with low purchasing power. The existence of this phenomenon needs to be conducted to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the entire food system, improve food security, and avoid potential shortages of food. The role of the government in this matter is very necessary to maintain domestic food security after the COVID-19 pandemic. Stimulus is needed in the agricultural sector in the hope of increasing crop production [32]. In addition, strategies that can be implemented to encourage the development of urban horticulture include the provision of technical innovation, organizational innovation, and policy and institutional support [33].

5. The impact of the pandemic on household food security and food supply chains

Food security is a condition of fulfilling sufficient food for the community, both in quantity and quality, at affordable prices. There are three important aspects in food security, as the aspect of food availability or production, the distribution aspect, and the consumption aspect. If food is available but the distribution is disrupted, it will affect community food security, and this happened at the beginning of COVID-19. Social restriction resulted in food distribution being constrained to consumers. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the distribution of food was constrained, so the supply of food was reduced, thus threatening people’s food security [34, 35]. Many countries have problems in producing food during a pandemic, one of which is due to limited manpower, so the harvest was not optimal [36, 37].

In urban areas, limited land for agricultural development causes most of the food ingredients to be imported from outside the city. Urban areas are highly dependent on food-producing areas, which are located outside cities. However, so far, the urban community’s food supply has always been fulfilled, supplied from outside the city and within the city itself. In urban areas, agricultural production is conducted on limited lands owned by the community itself, developers, and the government that have not been utilized.

The social restriction has opened opportunities for companies engaged in online sales, such as: SayurBox and Etanee, SayurBox offers 15 types of vegetables to consumers and Etanee offers 95 types of vegetables and 28 types of fruit [38, 39]. Vegetables that are in high demand in the market are shallots, garlic, potatoes, peeled sweet corn, and several types of leafy vegetables. However, online sales are still limited to urban and buffer zones (Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi, and Bandung).

According to the World Bank [40], the COVID-19 pandemic can cause disruptions to the distribution and production of agricultural products, which are also food products for people’s needs. COVID-19 caused labor mobility limitations, changes in consumer demand, the closure of food manufacturing facilities, limited food trade regulations, and financial constraints in the food supply chain [41]. The food supply chain was disrupted in countries that imposed a lockdown system to suppress the spread of COVID-19 [42, 43, 44, 45]. The lockdown in the city has raised awareness of how crucial it is for residents to have access to food [46]. Movement restrictions, including restrictions on the movement of (agricultural and other) labor and supplies, are likely to disrupt food production as well as food-related logistics and service, posing a challenge to the system’s ability to provide enough affordable and nutritious food for everyone [47].

The social restriction has caused many stalls and stores to close and has limited access points for food from agricultural areas’ production centers to urban areas. This circumstance causes agricultural production upstream and may cause food prices to fall, immediately affecting farmers, ranchers, and fishers [48]. On the other hand, a lockdown can cause a decrease in food stocks and increase prices due to delays in food distribution [43]. People tend to do stockpiling on food during the lockdown period, increasing the demand for food. In early days of the pandemic, panic buying had caused the run out of food stock in the market.

For example, fulfilling the Special Capital Region of Jakarta Province’s food demands is a barometer of national food needs. Because Jakarta is the national capital and the most populous province in Indonesia, with a population of 10,609,700 people (the sixth biggest province in Indonesia) [49], this population directly affects the high demand for food and competition for the use of land resources. Food requirements in Jakarta still depend heavily on food imports from other regions [50].

Jakarta Province engages in inter-regional commerce to address food demands. This business activity creates a distribution network in Jakarta that links food producers with end users and is remarketed to other regions [51]. Food availability depends on the condition of distribution facilities, transportation, and other infrastructure, which will also impact the stability of food prices in Jakarta. Due to transportation issues caused by social restrictions in Jakarta Province, some products, ingredients, or food raw materials are either unavailable or challenging to get. A robust logistical system is required to overcome the long-distance barrier by providing adequate infrastructure (roads, ports) and a modern cold chain system for perishable commodities [48].

Two aspects that can change the food supply chain’s long-term effects during and after the pandemic are expanding the online grocery delivery market and customers’ preference for “local” food supply chains [52]. In the face of the COVID outbreak, 70% of customers in the United States reduced their food shopping frequency and chose online marketing [53]. People’s behavior on internet purchasing has shifted because of COVID-19. During the epidemic, they believed internet purchasing platforms were advantageous and provided convenient access to food and other commodities [54]. Online agricultural commodities marketing platforms may help farmers market their crops. Although the proportion of local farmers using the internet doubled at the start of the 2020 pandemic, only a select few producers and consumers may be able to take advantage of online sales due to the high costs of running online stores or the lack of a reliable internet connection [55].

Due to limited access to imported food, people pick local products as alternatives for necessary food. Local agriculture needs to focus on producing nutritious food like vegetable and fruit products. Moreover, as stated by Schreiber et al. [55], local farmers’ adaptability and redundancy helped to maintain the local food chain during the outbreak of a worldwide epidemic. Urban farming is an excellent effort for the movement toward food sovereignty. There is a necessity to promote reflexive consumption by including urban gardeners in urban consumer organizations and to link urban consumers with local producers [56].

6. Government strategy to sustain participatory urban farming

The pandemic gives an important lesson that food availability is the main thing in maintaining food security. During the lockdown, the government encouraged people to stay at home and conduct useful activities at home. Initially, the government encouraged urban farming activities, especially for low-income people where food costs sometimes soared beyond other needs. However, this has changed along with the impact caused by the pandemic. Difficult access to food during the lockdown caused the food system to be disrupted from upstream to downstream and at the same time the availability of local food was not sufficient for the food needs of the local community. The supply of nutritious food is reduced, resulting in fears of food insecurity in the community.

Currently, urban farming is focused on food crops to meet food needs in times of crisis such as a pandemic. Programs related to urban farming activities to the community to foster farmer groups so that they can be adopted and diffused to the surrounding community. The program is designed in dense neighborhoods that do not have large areas of land and then utilized by farming vegetables, fruits, and family medicinal plants, in addition to making ends meet, expected to bring additional income to the family [18].

To encourage community participation in urban farming, the government provides capital assistance in the form of assistance, in the form of vegetable seeds, liquid organic fertilizers, and planting media as well as assistance from local extension workers in the form of technical guidance and motivation. Programs implemented such as

The involvement of the private sector in the form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is important to sustain the program in society. CSR is defined as the commitment of the business world to contribute to support the economic development process between companies in the local community and the wider community to improve living standards. Development companies that have enjoyed the benefits of the process of transferring paddy fields, and yards into residential areas, and business centers should contribute to the empowerment of local communities. The role of CSR in urban agriculture can be through the concept of developing conservation agriculture, and organic farming in urban agriculture. In addition, CSR can be in the form of financial support for training for farmers, development of superior agricultural land products, pilot plots, and purchase of tools and machinery for agricultural production facilities [57].

For instance, the engagement of PT. Indonesia Power Semarang in urban horticulture by building a greenhouse for farmer groups in Kemijen, Semarang City [58]. Based on the results of the Pertamina Company’s CSR program report, replacing hydroponics that initially used Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes into floating rafts with used styrofoam is considered effective and can improve people’s welfare in Mariana Village, Palembang [59]. Strategies that can be implemented to encourage the development of urban horticulture include the provision of technical innovation, organizational innovation, and policy and institutional support [33].

7. Conclusion

The importance of urban farming should have encouraged the participation of people in the program. Though the success stories and benefits of urban farming have been admitted, the sustainability of the urban farming movement still requires government assistance and intervention, and private involvement through CSR. The government must support infrastructure both in terms of policy and physical implementation to facilitate the establishment of a network of business partnerships between producer farmers and various market actors in a market chain until these agricultural products reach the consumer level. This is required to step up into commercialization and industrialization of urban farming rather than only self-sufficiency.

References

- 1.

Handayani W, Nugroho P, Hapsari DO. Kajian potensi pengembangan pertanian perkotaan di kota semarang. Journal of Riptek. 2018; 12 :55-68 - 2.

Poulsen MN, Spiker ML, Winch PJ. Conceptualizing community buy-in and its application to urban farming. Journal of Agricultural Food System Community Development. 2014; 5 :161-178 - 3.

Ackerman K. The Potential for Urban Agriculture in New York City: Growing Capacity, Food Security, and Green Infrastructure. New York, USA: Urban Design Laboratory, Earth Institute, Columbia University; 2012 - 4.

Almalki FA, Soufiene BO, Alsamhi SH, Sakli H. A low-cost platform for environmental smart farming monitoring system based on iot and uavs. Sustainable. 2021; 13 :1-26 - 5.

Wittman H. Food sovereignty: A new rights framework for food and nature? Environmental Society. 2011; 2 :87-105 - 6.

Weiler AM, Hergesheimer C, Brisbois B, Wittman H, Yassi A, Spiegel JM. Food sovereignty, food security and health equity: A meta-narrative mapping exercise. Health Policy and Planning. 2015; 30 :1078-1092 - 7.

Patel RC. Food sovereignty: Power, gender, and the right to food. PLoS Medicine. 2012; 9 :e1001223 - 8.

Slegers MFW. “If only it would rain”: Farmers’ perceptions of rainfall and drought in semi-arid Central Tanzania. Journal of Arid Environments. 2008; 72 :2106-2123 - 9.

Siegner A, Sowerwine J, Acey C. Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the Nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability. 2018; 2018 :10 - 10.

Chihambakwe M, Mafongoya P, Jiri O. Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture as a pathway to food security: A review mapping the use of food sovereignty. Challenges. 2019; 2019 :10 - 11.

Knuth L, Vidar M. Constitutional and Legal Protection of the Right to Food around the World. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2011 - 12.

Kementerian Pertanian RI. Petunjuk Teknis Optimalisasi Pemanfaatan Lahan Pekarangan Melalui Kawasan Rumah Pangan Lestari (KRPL). Jakarta: Ementerian Pertanian Ri Badan Ketahanan Pangan Pusat Penganekaragaman Konsumsi Dan Keamanan Pangan; 2020 - 13.

Ashari N, Saptana N, Purwantini TB. Potential of use backyard land for food security. Forum Penelit Agro Ekon. 2016; 30 :13 - 14.

Aref F. Farmers’ participation in agricultural development: The case of Fars province, Iran Indian . Journal of Science and Technology. 2011;4 :155-158 - 15.

Irwan SNR, Sarwadi A. Lanskap Pekarangan Produktif Di Permukiman Perkotaan Dalam Mewujudkan Lingkungan Binaan Berkelanjutan. Semin Nas Sains dan Teknol. 2015; 1 :1-11 - 16.

Ferdous Z, Datta A, Anal AK, Anwar M, Khan ASMMR. Development of home garden model for year round production and consumption for improving resource-poor household food security in Bangladesh NJAS - Wageningen . Journal of Life Science. 2016;78 :103-110 - 17.

Kementerian Pertanian. Petunjuk Teknis Pekarangan Pangan Lestari (P2L). Jakarta: Badan Ketahanan Pangan Kementerian Pertanian; 2021 - 18.

Rouli Alodia A, Olivia Sitompul A, Kesehatan Masyarakat F. Urban farming selama pandemi covid-19 serta manfaatnya bagi lingkungan dan gizi masyarakat. Journal of Kesehat. 2021; 2 :337-345 - 19.

Handoyo T, Darsin M, Widuri LI. Kolam gizi akuaponik untuk ketahanan pangan masyarakat urban kelurahan karangrejo kabupaten jember di masa pandemi covid-19. Panrita Abdi-Jurnal Pengabdi. 2022; 6 :114-122 - 20.

Murdad R, Muhiddin M, Osman WH, Tajidin NE, Haida Z, Awang A, et al. Ensuring urban food security in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic — Is urban farming the answer? A review. In: Sustainability. Switzerland: MDPI; 2022; 14 (7). DOI: 10.3390/su14074155 - 21.

Noviana F, Fadli ZA, Hastuti N. Sosialisasi budikdamber sebagai salah satu upaya penguatan ketahanan pangan rumah tangga selama masa ppkm akibat pandemi covid-19. Harmon. J. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy; 5 :68-73 - 22.

Setiawan B, Rahmi DH. Ketahanan Pangan, Lapangan Kerja, dan Keberlaniutan. Kota: Studi Pertanian Kota di Enam Kota Indonesia; 2004 - 23.

Fauzi AR, Ichniarsyah AN, Agustin H. Pertanian perkotaan: urgensi, peranan, dan praktik terbaik. Journal of Agroteknologi. 2016; 10 :49-62 - 24.

Karyani T, Djuwendah E, Sukayat Y. Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Di Masa Pandemi Melalui Pertanian Organik Di Lahan Pekarangan Kawasan Perkotaan Jawa Barat. Dharmakarya. 2021; 10 :139 - 25.

Bulgari R. The impact of covid-19 on horticulture: Critical issues and opportunities derived from an unexpected occurrence. Horticulturae. 2021; 2021 :7 - 26.

Salman TM, Matloobi M, Wang Z, Rahimi A. Understanding the dynamics of urban horticulture by socially-oriented practices and populace perception: Seeking future outlook through a comprehensive review. Land Use Policy. 2022; 122 :106398 - 27.

Suryantini A. Perceived Benefits and Constraints in Urban Farming Practice during COVID-19. IOP Conference Series Earth Environmental Science. 2021; 2021 :686 - 28.

Wicaksono FY, Nurmala T. Respons Peserta Pelatihan Urban Farming Yang Ramah Lingkungan Secara Online. Dharmakarya. 2021; 10 :154 - 29.

Wachdijono WS, Trisnaningsih U. Penerapan Urban Farming “ Vertikultur ” untuk Menambah Pendapatan Rumah Tangga di Kelurahan Kalijaga Kecamatan Harjamukti Kota Cirebon Pros . Seminar Nasional Unimus. 2019;2 :374-381 - 30.

Purba S, Amir IT. Household perception of urban farming for environmental coastal area HouseholdB (Case Study District Gresik). IOP Conference Series Earth Environmental Science. 2021; 2021 :695 - 31.

Roubík H, Lošťák M, Ketuama CT, Procházka P, Soukupová J, Hakl J, et al. Current coronavirus crisis and past pandemics - what can happen in post-COVID-19 agriculture? Sustainable Production Consumers. 2022; 30 :752-760 - 32.

Churiyah M, Dharma BA. Optimalisasi Pemberdayaan Kelompok Urban farming untuk meningkatkan ketahanan pangan pasca pandemi covid 19. Portal Riset dan Inovasi Pengabdian Masyarakat (Prima); 2022; 2 (1):79-89 - 33.

Sastro Y. Pertanian perkotaan: peluang, tantangan, dan strategi pengembangan. Bul. Pertan. Perkota. 2013; 3 :29-36 - 34.

Mouloudj K, Bouarar AC, Fechit H. The impact of Covid 19 pandemic on food security. Les Cah du Cread. 2020; 36 :159-184 - 35.

Siche R. What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture? Science Agropecu. 2020; 11 :3-9 - 36.

Gregorio G, Ancog R. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural production in Southeast Asia: Toward transformative change in agricultural food systems. Asian Journal of Agricultural Development. 2020; 17 :3-51 - 37.

Dev D, Kabir K. COVID-19 and food security in Bangladesh: A chance to look Back at what is done and what can Be done. Journal of Agricultural Food System and Community Development. 2020:1-3 - 38.

Sayurbox. Big Alpha - Mengenal Sayurbox. Alternatif Belanja: Sayur dan Buah Online; 2023 - 39.

Venny S. Penjual sayuran online alami permintaan berlipat-lipat saat pandemic. Jakarta: Kontan; 25 Apr 2020 - 40.

World Bank. A Shock like No Other: The Impact of COVID-19 on Commodity Markets. Washington DC: World Bank; 2020 - 41.

Aday S, Aday MS. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Quality Safish. 2020; 4 :167-180 - 42.

Abhishek BV, Gupta P, Kaushik M, Kishore A, Kumar R, Sharma A, et al. India’s food system in the time of covid-19. Economical Political Weekly. 2020; 55 :12-14 - 43.

Fawzi NI, Qurani IZ, Rahmasary AN. COVID-19: Implication to Food Security. Jakarta. 2020. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15160.90888 - 44.

Hobbs JE. The Covid-19 pandemic and meat supply chains. Meat Science. 2021; 181 :108459 - 45.

Chari F, Muzinda O, Novukela C, Ngcamu BS. Pandemic outbreaks and food supply chains in developing countries: A case of COVID-19 in Zimbabwe. Cogent Bus Man. 2022; 9 :2026188 - 46.

Pulighe G, Lupia F. Food first: COVID-19 outbreak and cities lockdown a booster for a wider vision on urban agriculture. Sustainable. 2020; 12 :5012 - 47.

Bakalis S, Valdramidis VP, Argyropoulos D, Ahrne L, Chen J, Cullen PJ, et al. Perspectives from CO+RE: How COVID-19 changed our food systems and food security paradigms. Current Research Food Science. 2020; 3 :166-172 - 48.

Putri NA, Sitompul FR. Smart food supply chain: Recommendations after COVID-19 pandemic in agricultural industry. In: Ttialih R, Wardiani FE, Anggriawan R, Putra CD, Said A, editors. Indonesia Post-Pandemic Outlook: Environment and Technology Role for Indonesia Development. Jakarta-Indonesia: Overseas Indonesian Student’s Alliance & BRIN Publishing; 2022. pp. 209-225 - 49.

BPS. STATISTIK Indonesia 2022. Jakrta: BPS Indonesia; 2022 - 50.

Anugrah IS, Saputra YH, Sayaka B. Dampak Pandemi Covid-19 Pada Dinamika Rantai Pasok Pangan Pokok Dampak Pandemi Covid-19: Perspektif Adaptasi dan Resiliensi Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian. 2020; 3 :297-319 - 51.

Sulaiman AA, Jamal E, Syahyuti KIK, Wulandari S, Torang S, Hoerudin BF, et al. Menyangga Pangan Jakarta: Sebuah Konsep Keterkaitan Pangan Kota Besar dan Wilayah Peyangga. Jakarta: IAARD Press; 2017 - 52.

Hobbs JE. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2020; 68 :171-176 - 53.

Barman A, Das R, De PK. Impact of COVID-19 in food supply chain: Disruptions and recovery strategy. Current Research Behavioural Science. 2021; 2021 :2 - 54.

Shahzad MA, Razzaq A, Qing P, Rizwan M, Faisal M. Food availability and shopping channels during the disasters: Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed peoples’ online food purchasing behavior? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2022; 83 :103443 - 55.

Schreiber K, Soubry B, Dove-McFalls C, MacDonald GK. Diverse adaptation strategies helped local food producers cope with initial challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic: Lessons from Québec, Canada. Journal of Rural Studies. 2022; 90 :124-133 - 56.

Nasution Z. Indonesian Urban Farming Communities and Food Sovereignty. 2015 - 57.

Muljawan RE. Kontribusi Perusahaan Pengembang Terhadap Pemberdayaan Petani Perkotaan dalam Mewujudkan Ketahanan Pangan. Pros. Konf. Nas. Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. dan Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019; 2 :1478-1483 - 58.

Wulandari R, Martuti NKT, Syamsul MA, Mutiatari DP. Peran Program CSR PT. Indonesia Power Semarang PGU Dalam Mendukung Pertanian Perkotaan di Kelurahan Kemijen. Journal of Abdimas. 2021; 25 :225-232 - 59.

Hilmy SI, Poetri IDM, Putri BA. Efektifitas Program CSR Hidroponik Rakit Apung Terhadap Peningkatan Taraf Hidup Penerima Manfaat Program. Ampera: A Research Journal of Political Islam Civilization. 2022; 3 :156-164