The five essential principles of management of pain in CKD.

Abstract

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience a high symptom burden, both physical and psychological, that is underrecognized and undertreated. The excessive symptom burden appreciably influences the existence of sufferers and their families. There is an increased prevalence of unpleasant physical and psychological symptoms in patients with CKD. These symptoms impact the Quality of life (QoL) adversely. Routine evaluation and control of those signs and symptoms for the duration of the disorder trajectory ought to be a priority. While managing symptoms, the toxicity of medications that impair residual kidney function, delayed drug clearance, and the impact of dialysis on drug clearance should be considered. The standard rule is to maintain cognitive, physical, and kidney function and deal with the symptom burden with the awareness that management priorities may change with time. Clear communication and shared decision-making need to manual deciding on conservative kidney management, advanced care planning, and psychosocial support alongside dialysis.

Keywords

- palliative care

- shared-decision making

- terminal symptoms

- chronic kidney diseasep

1. Introduction

Patients with CKD experience debilitating physical and psychological symptom burden, independent of the stage of CKD, as suggested by recent evidence [1]. With a median of five to six symptoms, this high burden harms the quality of life in these patients, similar to patients suffering from malignancies [2, 3]. Nearly 20% of dialysis patients withdraw from dialysis before the terminal event and, increasingly, older, frail patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) chose not to be initiated on dialysis when its utility may be of little or no benefit and also potentially harmful [4]. Hence, treatment options for patients with eGFR category 5 CKD should include shared decision-making and holistic patient-centered care, ensuring the quality of life (QOL), active symptom management, and advanced care planning. It includes all measures that would delay the progression of kidney disease [5].

2. Definition and principles

Palliative care refers to the crucial yet comprehensive management of the physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and existential needs of patients and families in serious illness. It is aimed at providing the best possible quality of life by ameliorating suffering, controlling symptoms, and restoring functional capacity while maintaining sensitivity towards the patient’s personal, cultural and spiritual beliefs. The change of terminology from “kidney palliative care” to “kidney supportive care” reinforces this comprehensive management rather than implying a limiting belief that palliative care is directed at only patients who are at the end of life [6].

3. The need for palliative care in CKD

CKD patients who undergo comprehensive palliative care management experience less symptom burden at the end of life, receive care according to their preferences, and also are provided with the opportunity to use hospice care. These patients are less likely to die in an acute setting or an intensive care unit requiring more invasive interventions. They enjoy a better quality of life, while also reducing the cost of healthcare [7].

4. Challenges in palliative care

Enabling and integrating palliative care into routine care for CKD patients comes with several challenges, such as regional differences, deciding on the priorities at the frontline, turnover of frontline staff and administrative leadership, sensitivity to the cultural and spiritual practices. A thoughtful combination of health care- and patient-focused evidence-based strategies has to be formulated to ensure more effective care. Despite potential benefits, palliative care is underutilized by advanced CKD patients in many parts of the world, for instance, the lesser availability of such facilities to blacks. Also, the time of referral to hospice care plays a vital role, in that, patients who are referred to hospice care late, are more likely to be dependent on acute care in a hospital setting [8]. Hence, identification of the right patient, shared- decision making and advanced care planning serve to be important factors that need to be considered for effective delivery of palliative care.

5. Components of palliative care

The core components that are integral for the effective delivery of palliative care include:

Shared decision making

Quality of life (QoL) assessment

Advanced care planning

Prognosis

Palliative & Hospice Care

Terminal symptoms management

5.1 Shared decision making

Shared decision-making is the key factor that must be incorporated into all other components from recognizing and management of debilitating symptoms, sharing prognosis, advanced care planning to delivery of end-of-life care and bereavement support. It is essential to incorporate the patient’s needs and adapt to his or her lifestyle, including family, social and cultural beliefs, in relieving suffering [9, 10].

5.2 Quality of life (QoL) assessment

Quality-of-life assessment should begin with the time of diagnosis of CKD continue typically every two months in patients on dialysis and every three months in patients with advanced CKD, yet not on dialysis until death. Symptom assessment is integral for assessing the quality of life, as these symptoms impact the patient’s functional status.

Some of the commonly used validated tools are the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)- Revised: Renal [10, 11], Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale- Renal (IPOS-Renal) [12, 13], and Dialysis Symptom Index [14]. These validated questionnaires help in assessing and managing the symptoms systemically. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment-Revised: Renal, a widely used assessment tool, uses a visual analog scale(VAS) with a super-imposed 0 to 10 numerical rating scale, which assesses pain, activity level, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, wellbeing, shortness of breath, pruritus, sleep, and restless legs. A caregiver can complete several items on the questionnaire if the patient is too ill to participate in the evaluation.

In addition, assessment of frailty is particularly useful as it helps in identifying vulnerable individuals to problems involving cognition, medication use, continence, balance, and social support, all of which are common challenges for patients with advanced CKD. Frailty, initially described in the geriatric population, has now been recognized as a predictor of mortality, quality of life, and functional status in patients with advanced CKD [15]. The frailty assessment tools include Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [16] and the Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS) [17]. Early recognition of mild to moderate frailty in CKD patients will help in optimizing physical activity and nutrition or planning appropriate advanced care.

5.3 Advanced care planning

Advanced care planning (ACP) involves patient-centered care with the understanding and sharing of the patient’s values, life goals, and preferences regarding aspects of future medical care at times of incapacity. It also helps the family members and surrogates with decision-making and lessens their distress and bereavement. Hence ACP must be incorporated into routine care for all patients with advanced CKD, and with periodic reassessment, it helps ensure that the patient has had enough time to think and make well-informed decisions regarding future care, as their health status may decline.

ACP is most needed in the following high-risk patients:

“No” as an answer to the question: “would you be surprised if the patient died in the next 12 months?” [18].

Frail patients, with functional or cognitive decline, or repeated unplanned admissions.

Patients with poor tolerance of dialysis with a change in modality, those who choose or are considering conservative kidney management or withdrawal from dialysis

Patients with poor or declining quality of life, with high physical or psychosocial symptom burden.

Patients with decision-making difficulty regarding goals of care.

ACP primarily is based on the perspectives of patients with advanced CKD. Hence, it is essential that the patient is given adequate time to think, reflect on their decisions of advanced care. This, however, shall not be addressed in a single conversation, and hence requires periodic review to gain a full understanding of the patient’s beliefs and values. Another effective way of planning involves, including the patient’s family, however not making decisions solely on their perspectives.

5.4 Prognosis

The treating nephrologist needs to provide details of the prognosis to facilitate patient-centered decision-making. The available tools to assess prognosis include: Charlson comorbidity score [19], the patient’s functional status, and the surprise question (“Would I be surprised if this patient died within the next year?”) [18]. In spite of the lack of sensitivity and specificity of the available tools, they help in identifying high-risk patients who can be treated with specific supportive care interventions.

It is important to discuss prognosis with patients who are deciding between conservative kidney management and dialysis and with patients who are contemplating withdrawal of dialysis. Mean survival from the last dialysis treatment to death in a patient who stops dialysis is 7 to 10 days, with a range of 2 to 100 days, with longer survival in those with significant residual kidney function. Treating nephrologists need to identify patients for whom dialysis does not provide survival advantage or better QoL, as these patients may be treated with conservative kidney management.

5.5 Palliative and hospice care consultation

In patients, whose suffering (especially spiritual and psychological support) cannot be addressed by the kidney care team, palliative care consultation should be sought. Specialist palliative care services may also be sought to address considerations at the end of life, involving both symptom management and location of death. Also, referral to hospice, is particularly relevant for patients withdrawn from dialysis or who have chosen conservative kidney management and are nearing the end of life when the eGFR is typically ≤5 mL/min/1.73 m2.

While there is no uniform policy about continuing dialysis for hospice patients, dialysis has to be decided on an individual basis. Also, patients with a terminal condition not related to ESKD may be eligible to receive hospice services both under the ESKD benefit and the hospice benefit. To facilitate coordinated care, it is imperative that providers should work with their local hospice agencies and palliative care services to educate patients and families, including nephrologists, and clinic and dialysis personnel on the benefits of hospice for the advanced CKD population.

6. Terminal symptoms management

For patients with advanced CKD patients, the terminal symptoms which are described further, cause a great deal of distress and agony more than the death itself. In a study conducted by Alexsson et al. [20], out of 472 patients who were expected to die from advanced CKD, pain was the most prevalent symptom (69%), followed by others such as respiratory secretions (46%), anxiety (41%), confusion (30%), while shortness of breath (22%), and nausea (17%) were found in a lesser percentage of patients. In most other studies, pain was the most common symptom towards the end of life (in 42 to >90% of patients) [21, 22]. Other less commonly reported symptoms were weakness, agitation, depression, myoclonus or muscle twitching, dyspnea, fever, diarrhea, dysphagia, and nausea. Much emphasis is made on terminal symptoms management, as in terminal stages, patients and caregivers experience anxiety, depression, and have practical concerns.

6.1 Pain

Pain is the most common symptom experienced by almost one-third of CKD patients. The origin of pain in CKD can be musculoskeletal or neuropathic. The majority of the patients experience moderate to severe intensity of pain. Management of pain should involve medical history, primary diagnosis, comorbidities, physical examination, psychological status, functional status, and QoL.

6.1.1 Determination of pain intensity

Following are the screening tools for assessing the intensity of pain:

Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Version 2 (m-ESAS v.2)

IPOS-Renal (POS-renal)

Further follow-up can be achieved by using a separate visual pain.

6.1.2 Causes and chronicity of pain

Proper management of pain involves identifying triggers, frequency, and chronicity of pain. Patients experience recurrent pain from cannulation of arteriovenous fistula, leg cramps, steal syndrome. Management of these symptoms over some time becomes challenging as they are somatosensory or psychological.

6.1.3 Type of pain

Identifying the type of pain helps in choosing the appropriate analgesia in ameliorating the symptom. Nociceptive pain responds to non-opioid and opioid analgesics, at least in the short term. Neuropathic pain responds poorly to Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids and often requires adjuvant drugs, that have a primary indication other than pain. Since most chronic pain in CKD is of mixed etiology, addressing the neuropathic component first with adjuvant therapy avoids inadvertent use of opioids.

6.1.4 Goals of therapy

Management of pain should lead to improved QoL, by allowing routine day-to-day work. This is achieved by having a realistic aim to reduce pain to a tolerable level (at least by 30% on the pain scale). Treating chronic pain encompasses both non-pharmacological and pharmacological measures.

Non-pharmacological measures include (not graded): aerobic exercise, acupressure, physiotherapy, local heat application, all of which help in reducing the pill burden of analgesia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, and relaxation help in reducing drug dependency among patients with neuropathic pain.

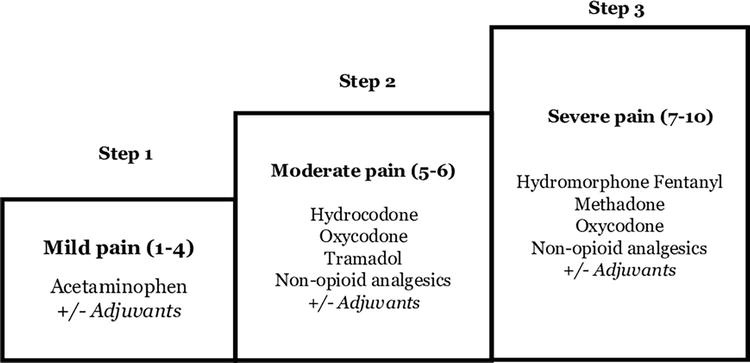

Pharmacological interventions in the management of chronic pain are usually done by following the World Health organization analgesic ladder (Figure 1) [23].

Figure 1.

The World Health Organization three-step analgesic ladder modified for patients with kidney failure.

The five essential principles that have to be considered within the context of advanced CKD are described in Table 1 [24].

| Principle | Description | Special consideration in CKD |

|---|---|---|

| 1. By mouth | Oral administration is the safest and preferred method. In case of uncertain ingestion or absorption, alternative routes such as transdermal, rectal or subcutaneous administration can be done. | Despite easy intravenous access in hemodialysis patients. It is usually avoided to optimize safety and minimize the risk of addiction. |

| 2. By the clock | For continuous or predictable pain, regular medications with additional ‘rescue’ doses should be administered | Some patients may require dosing post-hemodialysis to relieve pain, eg, gabapentin post-hemodialysis in patients with mild to moderate intensity of pain. Gradual as well as careful titration of analgesics is essential to avoid adverse events. |

| 3. By the ladder | Stepwise proceeding from non-opioids to low dose opioids, with the full tolerated dose being administered before moving on to next level. | Sustained release preparations are genrally not recommended, due to narrow therapeutic index, as well as increased rate of mortality with long-acting drugs. |

| 4. For the individual | The risk–benefit ratio on an individual case basis has to be assessed. The optimum dose of strong opioids is the amount at which there are no intolerable side effects while relieving pain. | Close attention to other influencing factors like physical, psychosocial and spiritual concerns is essential for a holistic management of chronic pain. |

| 5. Attention to detail | With changing nature of pain over time, regular reassessment becomes essential. | There are no studies on the long-term use of analgesia in CKD. Hence careful attention should be paid to efficacy and safety. |

Table 1.

A cautious stepwise approach to the introduction and titration of analgesics is outlined in Table 2.

| Trial each step for 1–4 weeks before progressing, depending on the severity of the pain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Start with adjuvant therapy If pain persists, ↓ Add a non-opioid +/− adjuvant therapy | 1st line: Gabapentin 50–100 mg p.o. at nighttime. If not effective, titrate the dose by 100 mg every 7 nights to a maximum of 300 mg at night-time 2nd line: Carbamazepine starting dose: 100 mg twice daily 3rd line: Tricyclic antidepressants, eg: amitriptyline starting at 10–25 mg daily, or doxepine starting at 10 mg daily | N/A |

| If pain persists, ↓ Add a non-opioid +/− adjuvant therapy ↓ Titrate slowly to ensure adequate pain relief | Acetaminophen, maximum of 3 g per day in addition to adjuvant therapy (adjuvant can be stopped if of no benefit or not tolerated) | Acetaminophen, maximum of 3 g per day Consider a topical NSAID, for eg; diclofenac gel 5% or 10% 2–3 times per day. If pain is localized to a small joint. |

| e.g; hydromorphone starting at 0.5 mg PO (0.2 mg subcutaneously) q4–6 h in addition to adjuvant therapy and acetaminophen. Additionally, consider buprenorphine, fentanyl and methadone | e.g; hydromorphone starting at 0.5 mg PO (0.2 mg subcutaneously) q4–6 h Additionally, consider buprenorphine, fentanyl and methadone | |

Table 2.

Management of neuropathic or nociceptive pain in CKD.

6.2 Uremic pruritus

In advanced CKD, uremic pruritus (UP) is a common and troublesome symptom, experienced in 46% of hemodialysis patients [5, 25, 26]. It affects multiple health-related QoL outcomes such as sleep, general mood, and social function and independently affects mortality. Uremic pruritus involves itching over large surface areas, without restriction to any dermatomal pattern. The pathogenesis of UP is often multifactorial; comprising of uremic neuropathy, increase in activity of μ-opioid receptors, substance P, inflammation from chronic systemic inflammation of skin or nerves. Multiple evidence stat that only a small proportion of cases have histamine as an implicating factor. Management involves the assessment of contributory and reversible factors. It is imperative to rule out a fungal skin infection, contact dermatitis, drug reactions before initiating treatment for UP. The following are the non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment options available for CKD patients (Table 3).

| Non-pharmacological treatment | Pharmacological treatment |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 3.

Treatment options for uremic pruritus.

6.3 Insomnia

The prevalence of sleep disorders in CKD ranges from 20%–83% among CKD patients and 50%–75% among ESKD patients [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. Sleep disorders are present from the early stages in CKD and affect both duration and quality of sleep. The most common sleep disturbance is excessive daytime sleepiness. These sleep disturbances can decrease QoL, impair immune system impairment and have a negative impact on cardiovascular disease, and increase mortality by causing sudden cardiac death. It can also lead to disordered neurocognition with impaired attention and poor work performance. The causes of insomnia in CKD are both physical and psychological, and the available modes of treatment of insomnia are as follows (Table 4).

| Non-pharmacological treatment | Pharmacological treatment |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 4.

Treatment options for insomnia.

6.4 Anxiety and depression

Depression is very common among CKD patients with its prevalence being three to four times higher compared to the general population [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. Depression is invariably associated with poor psychosocial and clinical outcomes and lower QoL. It is also associated with higher mortality, increased emergency department visits, hospitalizations, prolonged hospital stay, cardiovascular events, withdrawal from dialysis, and suicide. Both biological and behavioral causes are implicated as the etiology of depression in CKD/ESKD. The recommended screening tools include a two-question approach modified from the Patient Health Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and General Anxiety Disorder-7. Evidence states that approximately only 35% of those with diagnosable depression receive treatment. An improvement in depressive symptoms and psychosocial outcomes was observed when treated with a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy.

Following Table 5, enumerates the available modalities to treat depression in CKD patients.

| Non-pharmacological treatment | Pharmacological treatment |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 5.

Treatment modalities for depression in CKD:

6.5 Restless leg syndrome

The definition of RLS was revised during the National Institutes of Health consensus conference (2002), Bethesda, USA, to include [44, 45, 46]:

Urge to move the legs usually with unpleasant sensations in the legs; arms and other body parts are occasionally involved.

Symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity.

Symptoms partially or totally relieved by movement and as long as the activity continues.

Symptoms are worse during the evening or night than during the day.

Among the dialysis population, the prevalence of RLS ranges from 6.6–80%. Abnormalities in the dopamine pathway of the subcortex in the brain have been implicated as a major etiological factor in the pathogenesis of RLS. Other contributing factors include iron deficiency, anemia, hyperparathyroidism, elevated serum calcium and phosphorus, inadequate dialysis, and poor sleep hygiene. Nevertheless, RLS is associated with decreased QoL and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Table 6).

| Non-pharmacological treatment | Pharmacological treatment |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 6.

Treatment modalities for depression in CKD.

6.6 Gastrointestinal symptoms

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common, especially in patients with advanced stage of CKD, yet not on dialysis [44, 47]. Most patients after initiation of dialysis, have an improvement in symptoms and experience better appetite. If already on dialysis, adequacy of the same should be assessed and managed appropriately. Measures should be taken to correct factors contributing to inadequate dialysis and improve uremia.

6.6.1 Nausea, vomiting

Multiple factors such as uremia, drugs (e.g., opioids, antibiotics, and anticonvulsants), diabetic gastroparesis, and/or uremic gastropathy are implicated as etiological factors for nausea and vomiting in patients with CKD. The stated occurrence of nausea in advanced kidney failure is about 46%. If gastritis is a contributory factor, a short course of proton-pump inhibitors may be used. Prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide (10 mg q 8th hourly) (50% dose reduction when eGFR <40 ml/min/1.73 m2) and itopride can be tried for gastroparesis with close monitoring for any side effects especially extrapyramidal symptoms with metoclopramide. Haloperidol (0.5–2 mg q 12 h) or levomepromazine (12.5–25 mg q 8 h) is commonly used for nausea and gastrointestinal symptoms but requires dose reduction due to their propensity for cerebral sensitivity.

Another common symptom, xerostomia or dry mouth can be addressed using lozenges or ice chips. No specific medication is approved.

6.6.2 Constipation

Along with dietary restriction, poor appetite, drugs such as opioids, iron supplements, phosphate binders, can contribute to constipation. Non-pharmacological strategies include consuming fiber (20–38 gm/day) and fluid intake within an allowed dietary restriction and physical activity. Pharmacological recommendations include once-daily use of oral osmotic laxatives (lactulose 15–30 ml), stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl 5–15 mg PO), sodium picosulfate, and stool softeners.

6.7 Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a common worrisome symptom in patients with CKD Stage 5 [44]. Volume overload (pulmonary edema), cardiovascular cause, or anemia are attributed as causative factors.

For volume overload: treat with a trial of loop diuretics at the higher end of recommended dosing, initiation and intensification of dialysis, slow continuous ultrafiltration

For cardiac cause: identification of cardiac lesion and its correction, helps in relieving symptoms.

Other contributory factors, such as anemia should be corrected promptly, with iron supplementation and erythropoietin.

As management of dyspnea at home could be very difficult for the patient and family, the patient may be admitted to the hospital for the same. In the end stage, general measures to address hypoxia such as propped-up position, inhaled oxygen, and anxiolytics.

Small doses of opioids can be used for dyspnea end-of-life care.

Short-acting benzodiazepines like lorazepam 0.5–1.0 mg oral or sublingual at 6–8-h interval can be tried.

Especially at the end of life, midazolam at a dose of 1.25–2.5 mg can be given subcutaneously with close monitoring.

7. Palliative dialysis

Palliative dialysis is an approach that prioritizes quality of life over survival, by using patient-specific dialysis prescriptions. It requires integration of renal supportive care, discussion among the patient, family, and dialysis providers. It aims at relieving symptoms such as breathlessness rather than achieving biochemical parameters that represent conventional dialysis adequacy. Palliative dialysis does not translate to less dialysis or precursor for withdrawal of dialysis. It rather implies flexibility in issues such as blood pressure control, so that care can be tailored appropriately for each patient [48].

8. Withdrawal of dialysis

Conservative kidney management (CKM) is a continuation of all other services to ameliorate terminal symptoms however without initiation or continuation of dialysis. Following are the ideal scenarios where CKM is adopted [49, 50].

Patients who have one or more life-shortening comorbidities such as end-stage liver or heart failure.

Frail patients with significant preexisting functional or cognitive impairment, who may have worsening impairment on dialysis.

Patients residing in long-term care facilities.

Patients with irremediable physical or psychological symptoms, in whom dialysis may prolong life but will also prolong suffering.

Patients with irreversible intellectual incapacitation such that they cannot apprehend the process, risks, and benefits of dialysis in such a way that dialysis cannot be administered safely. Some examples of this include:

Patients without decision-making capacity whose advanced care directive or the substituted judgment of a health care proxy dictate CKM.

Patients who are unable to cooperate with the procedure of dialysis itself and are unable to react to specific surroundings or people, to such an extent they require restraints or sedation during dialysis

Patients in a persistent vegetative state.

9. Ethical issues in decision making

Ethical issues arise especially during times of withdrawal or withholding active care [51, 52, 53]. The key ethical principle, here, is non-maleficence, as the intention to either withhold or withdraw is to avoid or cease causing harm in situations where the treatment does not cause any benefits. The power of autonomy holds that patients have the right to accept or reject health care, which is medically indicated. Respecting autonomy implies respecting the patients’ own set of values, goals, experiences, and social relationships, which ultimately leads to different decisions taken by different patients in the same clinical situation.

As much as important it is, to respect the patient’s autonomy, especially during situations when he or she requests for withdrawal of care, it is the duty of the treating nephrologist, to identify the real motto behind the patient’s decision and to address any reversible or treatable psychological factors. High-quality discussions about what is important to patients and their families promote good decision-making and patient-centered care. It allows clinicians, patients, and families to avoid disagreements that could otherwise escalate into ethical conflicts. However, treatment options cannot be dictated based solely on the surrogate’s decisions.

A realistic tool that allows ethical decision making is Jonsen’s “Four Box Model”. The main benefit of this model is to balance medical decision-making elements that are important to health professionals with those patient-centered elements that are important to clinical decision-making, including preferences, quality of life, and other practical considerations.

10. Post-death assessment and bereavement care

As a part of routine quality assurance, some nephrology programs assess the quality of a patient’s end-of-life event [21]. Such assessment promotes the focus of attention towards ensuring advance care planning, symptom control, and effective communication among treating teams, patients, and their families. Bereavement support to families and involved caregivers (eg, dialysis unit staff, transporters, etc) can be extended by dialysis unit-sponsored memorial services. Support should be provided to all families and loved ones following the death of an ESRD patient, irrespective of referral to hospice care. Condolence letters and/or call from the nephrologist or other staff, attendance by the social team at the funeral, contact with a renal social worker, annual renal memorial service are some of the ways by which post-bereavement care is provided.

11. Conclusions

Although conservative kidney management is more and more recognized as an appropriate treatment choice for patients, who are unlikely to benefit from dialysis, there is still great variation in the current understanding and reputation of conservative kidney management as a distinct modality choice. With this comes exceptional variations in clinical practice and standards of care. Many patients undergoing conservative kidney management present with complex health scenarios, and most recommendations have to be personalized. Participation from patients play a vital role in decision-making. In a shared decision-making process, ensuring that all interventions are aligned appropriately with their values, preferences, and prognosis will go a long way.

References

- 1.

Pugh-Clarke K, Naish PF, Mercer TM. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease. Journal of Renal Care. 2006; 32 :156-159 - 2.

Brown SA, Tyrer FC, ClarkeAL L-DLH, SteinAG TC, et al. Symptom burden in patients with chronic kidney disease not requiring renal replacement therapy. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2017; 10 :788-796 - 3.

Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Edmonds P, Donohoe P, Carey I, Jenkins K, et al. Symptoms in the month before death for stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients managed without dialysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010; 40 :342-352 - 4.

Davison SN, Moss AH. Supportive care: Meeting the needs of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016; 11 (10):1879-1880 - 5.

Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes: Executive summary of the KDIGO controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney International. 2015; 88 :447-459 - 6.

Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, Nguyen L, Chacko R, Li Z, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2011; 16 (1):105-111 - 7.

Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176 (8):1095-1102 - 8.

O'Hare AM, Butler CR, Taylor JS, Wong SPY, Vig EK, Laundry RS, et al. Thematic analysis of hospice mentions in the health Records of Veterans with advanced kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2020; 31 (11):2667-2677 - 9.

Brown EA, Bekker HL, Davison SN, Koffman J, Schell JO. Supportive care: Communication strategies to improve cultural competence in shared decision making. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016; 11 (10):1902-1908 - 10.

Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Johnson JA. Cross-sectional validity of a modified Edmonton symptom assessment system in dialysis patients: A simple assessment of symptom burden. Kidney International. 2006; 69 :1621-1625 - 11.

Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Johnson JA. Longitudinal validation of a modified Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS) in hemodialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2006; 21 :3189-3195 - 12.

Murphy EL, Murtagh FE, Carey I, Sheerin NS. Understanding symptoms in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis: Use of a short patient-completed assessment tool. Nephron. Clinical Practice. 2009; 111 :c74-c80 - 13.

Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: The palliative care outcome scale. Palliative care Core audit project advisory group. Quality in Health Care. 1999; 8 :219-227 - 14.

Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, RotondiAJ FMJ, Levenson DJ, et al. Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: The dialysis symptom index. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004; 27 :226-240 - 15.

Chowdhury R, Peel NM, Krosch M, Hubbard RE. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2017; 68 :135-142 - 16.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005; 173 (5):489-489 - 17.

Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton frail scale. Age and Ageing. 2006 Sep; 35 (5):526-529 - 18.

Baddour NA, Robinson-Cohen C, Lipworth L, Bian A, Stewart TG, Jhamb M, et al. The surprise question and self-rated health are useful screens for frailty and disability in older adults with chronic kidney disease. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2019; 22 (12):1522-1529 - 19.

Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the Charlson comorbidity index for use in patients with ESRD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003; 42 (1):125-132 - 20.

Axelsson L, Alvariza A, Lindberg J, Öhlén J, Håkanson C, Reimertz H, et al. Unmet palliative care needs among patients with end-stage kidney disease: A National Registry Study about the last week of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2018; 55 (2):236-244 - 21.

Cohen LM, Germain M, Poppel DM, Woods A, Kjellstrand CM. Dialysis discontinuation and palliative care. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000; 36 (1):140-144 - 22.

Cohen LM, Germain MJ, Woods AL, Mirot A, Burleson JA. The family perspective of ESRD deaths. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005; 45 (1):154-161 - 23.

World Health Organization Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1990. pp. 7-21 - 24.

Davison SN. Clinical pharmacology considerations in pain Management in Patients with advanced kidney failure. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2019 Jun 7; 14 (6):917-931 - 25.

Simonsen E, Komenda P, Lerner B, Askin N, Bohm C, Shaw J, et al. Treatment of uremic pruritus: A systematic review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2017; 70 :638-655 - 26.

Davison SN, Tupala B, Wasylynuk BA, Siu V, Sinnarajah A, Triscott J. Recommendations for the care of patients receiving conservative kidney management: Focus on the management of chronic kidney disease and symptoms. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2019; 14 :626-634 - 27.

Fishbane S, Jamal A, Munera C, Wen W, Menzaghi F. KALM-1 trial investigators. A phase 3 trial of Difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382 (3):222-232 - 28.

Theofilou P. Association of insomnia symptoms with kidney disease quality of life reported by patients on maintenance dialysis. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2013; 18 :70-78 - 29.

Sabbatini M, Minale B, Crispo A, Pisani A, Ragosta A, Esposito R, et al. Insomnia in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2002; 17 :852-856 - 30.

Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, Fissell R, Andreucci VE, Fukuhara S, et al. Sleep quality predicts quality of life and mortality risk in hemodialysis patients: Results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS). Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2008; 23 :998-1004 - 31.

Benz RL, Pressman MR, Hovick ET, Peterson DD. Potential novel predictors of mortality in end-stage renal disease patients with sleep disorders. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000; 35 :1052-1060 - 32.

Novak M, Shapiro CM, Mendelssohn D, Mucsi I. Diagnosis and management of insomnia in dialysis patients. Seminars in Dialysis. 2006; 19 :25-31 - 33.

Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney International. 2013; 84 :179-191 - 34.

Hedayati SS, Yalamanchili V, Finkelstein FO. A practical approach to the treatment of depression in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney International. 2012; 81 :247-255 - 35.

Shirazian S, Grant CD, Aina O, Mattana J, Khorassani F, Ricardo AC. Depression in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: Similarities and differences in diagnosis, epidemiology, and management. Kidney International Reports. 2017; 2 :94-107 - 36.

Farrokhi F, Abedi N, Beyene J, Kurdyak P, Jassal SV. Association between depression and mortality in patients receiving long-term dialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2014; 63 :623-635 - 37.

Hedayati SS, Finkelstein FO. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2009; 54 :741-752 - 38.

Song MK, Ward SE, Hladik GA, Bridgman JC, Gilet CA. Depressive symptom severity, contributing factors, and self-management among chronic dialysis patients. Hemodialysis International. 2016; 20 :286-292 - 39.

Palmer SC, Natale P, Ruospo M, Saglimbene VM, Rabindranath KS, Craig JC, et al. Antidepressants for treating depression in adults with end-stage kidney disease treated with dialysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016; 2016 (5):CD004541 - 40.

Nagler EV, Webster AC, Vanholder R, Zoccali C. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety with recommendations by European renal best practice (ERBP). Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2012; 27 :3736-3745 - 41.

Murtagh F, Weisbord SD. Symptoms in Renal Disease: Their Epidemiology, Assessment, and Management. In: Supportive Care for the Renal Patient. USA: Oxford University Press; 2011 - 42.

Koch BC, Nagtegaal JE, Hagen EC, van der Westerlaken MM, Boringa JB, Kerkhof GA, et al. The effects of melatonin on the sleep-wake rhythm of daytime hemodialysis patients: A randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study (EMSCAP study). British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2009; 67 :68-75 - 43.

Yang B, Xu J, Xue Q, Wei T, Xu J, Ye C, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for improving sleep quality in patients on dialysis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2015; 23 :68-82 - 44.

Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO controversies conference on supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney International. 2015; 88 :447-459 - 45.

Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Medicine. 2003; 4 :101-119 - 46.

Gopaluni S, Sherif M, Ahmadouk NA. Interventions for chronic kidney disease-associated restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016; 11 :CD010690 - 47.

Oxford Fliss EM. Murtagh chapter ends stage kidney disease. In: Oxford Text Book of Palliative Medicine. 5th ed. USA: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 1-25 - 48.

Davison SN, Tupala B, Wasylynuk BA, Siu V, Sinnarajah A, Triscott J. Recommendations for the Care of Patients Receiving Conservative Kidney Management: Focus on management of CKD and symptoms. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2019; 14 (4):626-634 - 49.

Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009; 361 (16):1539-1547 - 50.

Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M. Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009; 361 (16):1612-1613 - 51.

Cerminara KL. The law and its interaction with medical ethics in end-of-life decision-making. Chest. 2011; 140 (3):775-780 - 52.

Weissman DE. Consultation in palliative medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997; 157 (7):733-737 - 53.

Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine. 7th ed. New York, New York, United States: McGraw Hill; 2010