Abstract

Gallbladder position anomalies are rare. Normally, the gallbladder is located at the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver between segments IV and V, covered by the peritoneum, and attached to the liver by its mesentery in the gall bladder fossa. Any position other than this is defined as a gallbladder position anomaly. Gallbladder ectopia variants may include floating, intrahepatic, retroperitoneal, and left-sided gallbladder, among others. According to some literature, floating gallbladder is the most common among these anomalies, occurring in 4.6% of population; however, there is no clear and adequate data on incidence and variants of gallbladder position anomalies. Because of their rare occurrence and lack of specific clinical and imaging features, their possible presence and clinical sequelae are not usually considered in clinical practice. This results in delayed diagnosis and treatment of sequelae, such as in gallbladder volvulus (GBV). Similarly, gallbladder position and associated biliary tree and vascular anomalies should be identified during the preoperative period. Failing to do this may have devastating outcomes. Though clinical impacts and management of gallbladder position anomalies are explained in some literature, they are not well covered by most of the currently available surgical books. To fill this gap, this chapter discusses the embryology, variants, prevalence, clinical impacts, and management of ectopic gallbladder as well as ways to increase the rate of preoperative diagnosis and methods to decrease adverse outcomes and morbidity.

Keywords

- gallbladder position anomalies

- gallbladder malpositions

- gallbladder ectopia

- gallbladder volvulus

- gallbladder hernia

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy

1. Introduction

Gallbladder position anomalies are rare [1, 2]. Normally, the gallbladder is located at the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver between hepatic segments IV and V. It is covered by the peritoneum and adhered to the liver by its mesentery in gall bladder fossa at cantle’s line to the right of the falciform ligament. Any position other than this is defined as gallbladder malposition [2, 3]. Gallbladder ectopia variants may include floating, intrahepatic, retroperitoneal, and left-sided gallbladder [2, 4]. According to some literature, floating gallbladder is the most common among these anomalies, occurring in 4.6% of population [5]; however, there is no clear and adequate data on incidence and variants of gallbladder position anomalies [1, 2, 3, 4, 6]. Floating gallbladder may result in volvulus in the presence of precipitating factors [5, 7]. The clinical impacts of ectopic gallbladder include [8]:

misdiagnosis of common gallbladder pathologies due to malposition or misdiagnosis of gallbladder volvulus (GBV) as acute cholecystitis

confusion in interpretation of diagnostic imaging

associated biliary tree and vascular anomalies

technical difficulties during surgery

Because of their rare occurrence as well as lack of specific clinical and imaging features, the possible presence and clinical sequelae of gallbladder position anomalies are not usually considered in clinical practice. This results in delayed diagnosis and treatment of sequelae, as in GBV [6, 7]. Gallbladder position and associated biliary tree and vascular anomalies should be identified preoperatively. Failing to do so may have devastating outcomes, such as biliary duct injury or major vascular injury with hepatic necrosis. Even though preoperative diagnosis of position anomalies is possible with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), most are still being diagnosed intraoperatively. Adequate knowledge of these anatomical variants of the gallbladder will help modify techniques like laparoscopic cholecystectomy and prevent injury in the presence of biliary tree and vascular anomalies. This chapter reviews gallbladder embryology, anatomy, position anomaly variants, pathogenesis, clinical significance, and treatment.

2. Anatomy and embryology of the biliary system

2.1 Embryology of the biliary tree

The hepatobiliary system develops as an endodermal outgrowth from the ventral surface of the distal fore gut when the embryo is 3 mm in size (approximately 4th week of gestation) (Figure 1A). This outgrowth is called the hepatic diverticulum. With further proliferation, when the embryo is 5 mm in size (approximately early 5th week of gestation), the hepatic diverticulum divides into larger cranial and smaller caudal buds. The cranial bud is called pars hepatica, which will differentiate into liver and intrahepatic ducts, and the caudal bud is called pars cystica, which will further differentiate into superior and inferior buds. The superior bud differentiated gallbladder and the cystic duct and inferior bud gives ventral pancreas (Figure 1B). At about 32 days of gestation, the primordial gallbladder and common bile duct (CBD) appear. When the embryo is 7–9 mm (approximately 6th week of gestation), the gallbladder and cystic duct emerge and connect with the CBD, forming the liver and intrahepatic ducts. Bile starts to drain to the duodenum when the embryo is 12 mm (8th week of gestation). Initially, the gallbladder precursor attaches to the ventral surface of the duodenal precursor, with differential growth rotation to the right occurring at this stage bringing about attachment to the dorsal aspect of the duodenum. This results in the gallbladder precursor lying at the free edge of the ventral mesentery. Further differential growth makes the gallbladder migrate to the anterior inferior surface of the right hepatic lobe where it become intrahepatic. At 12 mm (approximately 8th week of gestation), the gallbladder migrates, becomes extrahepatic, and attaches to the anterior inferior surface of the liver between hepatic segments IV and V. The ventral mesentery that lies between the liver and foregut will develop into a gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligament. That lies between Liver & anterior abdominal wall will persist as falcifarum ligament, contains obliterated umbilical vein (ligamentum teres) in its free edge. When the embryo is 6 mm in size (approximately early 5th week of gestation), the developing liver is supplied by two blood vessels: the right and left umbilical veins. The left umbilical vein becomes one of the afferent vessels to the liver, but the right umbilical vein atrophies when the embryo is 7 mm (at the end of 5th week of gestation). The left umbilical vein is later obliterated and becomes the falciform ligament, and the typical umbilical portion of the main portal vein is formed [9, 10].

Figure 1.

Hepato biliary system development. A. At 5th week of development showimg cranial & caudal hepatic buds. (taken from Sahu and Yang) [

If any disruption occurs during migration, gallbladder position variations may occur.

If any disruption occurs during gallbladder migration from the free edge of the ventral mesentery to the right lobe of the liver, the gallbladder may poorly attach to the liver or not attach at all, resulting in floating gallbladder or halting of gallbladder migration in the lesser omentum, mesocolon, abdominal wall/falciform ligament, retroduodenal area, and so on.

Failure of the gallbladder to migrate from the intrahepatic to extrahepatic surface at the 8th week of gestation may result in intrahepatic gallbladder.

The gallbladder may migrate to the left hepatic lobe rather than the right hepatic lobe, resulting in left-sided gallbladder.

If left umbilical vein atrophy and right umbilical vein persists, right left sided gallbladder will be formed. The persistent right umbilical vein may also be associated with atrophy or hypoplasia or agenesis of the right lobe of the liver with the consequence of retrohepatic or subdiaphragmatic gallbladder [1, 2, 3, 10, 11, 12, 13].

2.2 Gross anatomy of the gallbladder

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ located under the anterior inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver. It is adhered to the liver obliquely in the gallbladder fossa with the fundus extended anterolaterally and the neck extended inferomedially cranially and caudally, respectively. The gallbladder is 7–10-cm long, 3–4-cm wide, and 3-mm thick. Normally, it stores about 30–50 ml of bile, but it can accommodate up to 300 ml in its full distension. The anatomic parts of the gallbladder include the fundus, body, infundibulum, and neck. The fundus is the part of gallbladder that protrudes beyond the inferior surface of the liver. The part of the gallbladder between the fundus and infundibulum is the body. The tapering part from the body to the neck is the infundibulum. The neck connects the gallbladder with the hepatic duct through the cystic duct (Figure 2). Arterial supply is cystic artery from right hepatic artery. Cystic veins drain directly to portal veins. Lymphatic drainage is to the cystic lymph node at the gallbladder neck. Parasympathetic innervation is from the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve and sympathetic supply is from the hepatic and celiac plexus [13, 14].

Figure 2.

Anatomical parts of gallbladder.

2.3 Variants, epidemiology, and etiopathogenesis of gallbladder position anomalies

The gallbladder is normally located at the inferior surface of the liver between hepatic segments IV and V [1, 2, 15]. The gallbladder’s fundus and body are covered by the peritoneum and adhered to the liver with loose connective tissue [1]. Any position or attachment other than this is defined as gallbladder malposition [1, 2, 13].

Gallbladder position anomalies are rarely occurring conditions, with an incidence of 0.1–0.7% [1, 6, 16]. More commonly occurring position anomalies as reported in the literature include floating gallbladder, left-sided gallbladder, intrahepatic gallbladder, and retro displaced gallbladders.

Relatively rarely occurring position anomalies include anterior abdominal wall, falciform ligament, mesocolon, lesser omentum, retrodoudenal, retrorenal, and retropancreatic gallbladders, among others [2, 8]. Some literature has concluded that left-sided gallbladder is the most common gallbladder position anomaly with an incidence of 0.1–0.7% based on a single-center retrospective review of gallbladder position anomalies found on laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the prevalence in patients evaluated by imaging [6, 17, 18]. However, Sreekanth et al. [13] performed dissection on 45 cadavers to determine incidence of floating gallbladder and reported an incidence of 4.4%. In addition, since the first reported case of left-sided gallbladder by Hochstetter [19] in 1886 and GBV by Wendel [20] in 1896, there have only been 150 and 500 cases of these conditions, respectively. Based on these figures, the most commonly occurring gallbladder malposition is floating gallbladder, which occurs in 5% of the population [5, 7, 13]. Left-sided gallbladder is the second most common anomaly, with an incidence of 0.1–1.2% [3, 4, 17]. The third most commonly occurring malposition is intrahepatic gallbladder [4, 11, 15]. Because sample sizes are small, these studies may not reflect true incidence. Hence, to determine true incidence, cadaver dissection or MRCP-based multicenter, prospective randomized clinical trials should be conducted.

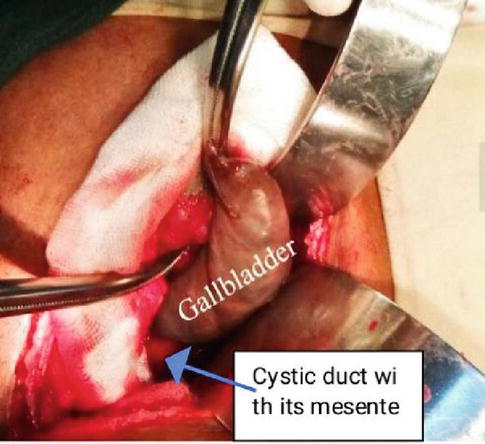

2.3.1 Floating gallbladder

A floating gallbladder is a freely mobile gallbladder in the peritoneal cavity due to poor attachment of the gallbladder mesentery to the liver. Four subvariants of floating gallbladder are described in the literature [5, 7]. In type 1, there is no mesenteric attachment with the liver except at the gallbladder’s cystic duct and artery. In type 2, there is mesenteric attachment between the gallbladder’s body, fundus, and cystic duct with the liver, but the gallbladder is long, redundant, and tortuous. This allows for the gallbladder to wander around and it may end up in the pelvis, left upper quadrant, or anterior to the spine. In type 3, there is a freely mobile fundus, which may result in gallbladder fundus torsion. Types 1–3 are congenital conditions. In type 4, poor gallbladder mesenteric attachment may occur, as in cases of liver atrophy or cirrhosis, peritoneal fat loss secondary to aging, and weight loss [7, 13, 20, 21]. These abnormal attachments predispose the gallbladder to torsion, herniation, strangulation, and increased stone formation [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39].

2.3.2 Left-sided gallbladder

Left-sided gallbladder is a rare malposition. It was first identified in 1886 by Hochstetter, and since then only 150 cases have been reported worldwide [3, 19]. The left-sided gallbladder is an anatomical variant in which the gallbladder is attached to the inferior surface of the left lobe of the liver to the left of the falciform ligament [10, 12, 14, 15, 40, 41]. Its prevalence is estimated to be 0.04–1.1% [3, 6, 22]. It is more common in females than males with a ratio of 2:1 [3] and the majority of cases are reported in Japan and Australia[]. According to current classification, there are three subtypes of left-sided gallbladder. Type 1 is called situs inversus viscerum. In this case, the gallbladder is found in the left upper quadrant of the liver. This condition is very rare. Type 2 is true left-sided gallbladder, also called sinistroposition. In this case, the gallbladder is found attached to the left lobe of the liver under hepatic segment III to the left of the falciform ligament. The exact etiology for this anomaly is not known, but there are three likely explanations. The first is the hypothesis that the gallbladder abnormally migrates from right to left. In this case, the cystic duct crosses the CBD to join at the right side. The second hypothesis is that an accessory gallbladder develops from the left duct and the main gallbladder either atrophies or fails to develop. In this case, the cystic duct joins the hepatic duct from the left side. In both cases, the cystic artery crosses the bile duct from right to left to supply the gallbladder. In true left-sided gallbladder, there is no associated intrahepatic vascular or duct anomalies. In the third hypothesis, the quadrate lobe of the liver fails to develop.

3. Right left-sided gallbladder is also called medio position or false left-sided gallbladder. In this case, the gallbladder is located normally, but the falciform ligament is abnormally located to the right of the gallbladder. During development, the right umbilical vein atrophies at the 6th week of gestation and the left umbilical vein is obliterated later and persists as the falciform ligament. If developmental disruption occurs to cause atrophy of the left umbilical vein and persistence of the right umbilical vein as the falciform ligament on the right side of the gallbladder, it falsely seems that the gallbladder is left sided [11, 22, 23, 24].

Associated anomalies with left-sided gallbladder include hepato-pancreatico-biliary (HPB) system, gastrointestinal system (GIS), and genitourinary system (GUS) anomalies. HPB anomalies occur more commonly than others and may include portal vein, bile duct, hepatic vein, and hepatic artery anomalies as well as hepatic segment IV atrophy and congenital hepatic cysts [3]. Portal vein anomalies include trifurcation, bifurcation, and other anomalies. Cystic duct anomalies in left-sided gallbladder may involve the cystic duct joining the right hepatic duct in 7.6% of cases, the left hepatic duct in 9.5% of cases, and the accessory duct in 2.4% of cases. The cystic duct joins the CBD from the right side in 65% of cases and from the left side in 9.5% of cases [42]. Other associated anomalies may include bile duct duplication, bile duct confluence in the umbilical fissure located to the left of the umbilical portion of the portal vein, and preduodenal portal vein, hepatic artery, and CBD anomalies. Annular pancreas, intestinal malrotation, and mobile right-sided colon are present [3]. Without considering situs inversus, 83% of left-sided gallbladder cases are true left-sided gallbladder and 16% are right left-sided gallbladder. The former has no associated vascular or biliary duct anomalies; rather, Calot’s triangle is disrupted. The latter has associated vascular and duct anomalies. Almost all right left-sided gallbladders have portal vein and biliary duct anomalies, and 20% have hepatic vein anomalies [3, 6].

2.3.3 Intrahepatic gallbladder

An intrahepatic gallbladder is a completely or partially embedded gallbladder in hepatic parenchyma. In normal development, the gallbladder is expected to migrate from an intrahepatic to extrahepatic location during the 8th week of gestation. Failure of this migration results in intrahepatic gallbladder, which is considered as developmental position arrest. Its estimated incidence ranges between 0.1 and 0.7% [8, 10]. Though its etiology is not clearly known, developmental disruption of the differential growth of the hepatic bud is a possible cause of intrahepatic gallbladder. During development, the growth and differentiation of the hepatic bud is controlled by different transcription pathways. Any disruption in these pathways may result in position anomalies. If the caudal bud (pars cystica) grows beyond the cranial bud, the gallbladder may be buried in the hepatic parenchyma [8, 10, 13].

2.3.4 Retro position gallbladder

Types of retro position gallbladder include subhepatic, retrohepatic, and retroperitoneal gallbladder, all of which are rare conditions. Retrohepatic gallbladder is usually associated with marked atrophy of the right hepatic lobe or agenesis and anomalies of the right hepatic vein and portal vein [1, 4].

2.3.5 Mesocolic gallbladder

Mesocolic gallbladder is very rare. In one patient, Teke et al. [2] discovered the gallbladder embedded deeply within the proximal portion of the transverse mesocolon. Etiology is not clearly known, but it seems a gallbladder poorly attached to the free edge of the ventral mesentery during development results in failure of developmental gallbladder migration to the gallbladder fossa [2].

2.4 Clinical impacts of gallbladder position anomalies

The clinical significance of ectopic gallbladder may include the following:

increased relative risk of cholelethiasis and its complications

clinical confusion or misdiagnosis

imaging misinterpretation

increased associated biliary tree and vascular anomalies

technical challenges during cholecystectomy

An ectopic gallbladder usually has poor function and a long narrow or curved cystic duct, which results in bile stasis and stone formation. Due to stasis, patients with ectopic gallbladder are more prone to develop complications like acute cholecystitis, gangrenous gallbladder, gallbladder empyema, perforation, peritonitis, and so on [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10]. Since there are no specific symptoms and signs for gallbladder malposition, it is usually diagnosed intraoperatively during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Rarely, it may be diagnosed during preoperative evaluation for hepatic surgery. The prevalence of stones in an ectopic gallbladder may reach up to 60% [8, 10], which is higher than the 15–20% prevalence of stones in a normally located gallbladder. Most of these patients present with biliary colic or acute cholecystitis and its complications. Since the origin of nerves supply for ectopic gallbladder is not changed, these patients have similar clinical features with normal anatomical variants of gallbladder. They present with right upper abdomen pain that radiates to the shoulder and associated nausea, vomiting, and fever [3, 8]. Sometimes some gallbladder ectopia may pose clinical confusion. For example, retroperitoneal or retrohepatic gallbladders with acute cholecystitis may have costovertebral angle tenderness instead of typical right abdominal pain, which leads to misdiagnosis of gallbladder ectopia as acute pyelonephritis [1, 2]. Delayed diagnosis and intervention may result in retroperitoneal gallbladder perforation with accumulation of bile or abscess, which may be misinterpreted as perinephric abscess during imaging [1].

The clinical sequelae of floating gallbladder includes GBV, gallbladder herniation, and gallbladder strangulation by the tip of the omentum.

GBV is a rare clinical condition; only about 500 cases have been reported since the first case reported by Wendel in 1896 [20]. Its incidence is estimated to be 1 in 365,520 hospital admissions [7, 21]. It is more common in females than males with a 3:1 ratio [7, 21, 22]. GBV is defined as twisting of the gallbladder with mesentery along its longitudinal axis [7, 20, 21, 22]. Its etiology is not known, but anomalous gallbladder mesentery attachment with liver seems to be a predisposing factor [7, 21, 22].

Additional predisposing factors include old age, weight loss, cirrhosis, kyphosis, vigorous adjacent gastrointestinal peristalsis, cystic artery atherosclerosis, and abnormally high insertion of cystic duct. Even though GBV can occur at any age, it usually occurs in those aged between 60 and 80 years [7, 22, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. This is due to increased loss of mesenteric fat and tissue elasticity in the elderly, which results in a freely mobile gallbladder. Kyphosis will increase the anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen, conferring adequate space for a wandering gallbladder to be twisted. The direction of torsion could be clockwise or counterclockwise; both occur with equal frequency. The direction of the twist is likely determined by the origin of vigorous peristalsis. Gastric and transverse colon peristalsis result in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. Based on degree of rotation, GBV can be classified as either complete (>180 degrees) or incomplete (<180 degrees) [7, 21, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. This classification has clinical importance. The former presents with acute onset of symptoms and short duration, whereas the latter present presents with intermittent symptoms of relatively long duration [7, 21, 22].

Because they are both rare and share similar clinical presentations, GBV is often misdiagnosed as calculous acute cholecystitis. Nowadays, about 75% of GBV cases are diagnosed intraoperatively. Late diagnosis and surgical intervention are associated with an increased mortality rate of 6% and thus preoperative diagnosis is recommended to decrease mortality and morbidity [7, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39].

2.4.1 Gallbladder herniation

Wandering gallbladder may herniate into foramen of Winslow (lesser sac). For example, in one review of six cases [23], floating gallbladder herniated into the lesser sac; half of patients had hernia with GBV and half did not have GBV. Kim et al. [5] reviewed fourteen cases and reported only four cases of gallbladder herniation with GBV; the remaining ten cases had gallbladder herniation with acute cholecystitis. Floating gallbladder may herniate into anterior abdominal wall defects [25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32], most commonly parastomal gallbladder herniation [29]. Unusual gallbladder herniations are also reported in the literature. For example, [31] reported a case of Spigelian gallbladder hernia, [27] reported a case of inguinal gallbladder hernia, and [28] reported a case of femoral gallbladder hernia. Another possible gallbladder hernia is to the thorax [32]. Almost all gallbladder hernias are diagnosed intraoperatively. Floating gallbladder may also be strangulated by the tip of the omentum, which is attached to the anterior abdominal wall [25]. Female gender and old age are sole risk factors. The complications of gallbladder herniation include gallbladder torsion, cholecystitis, Mirizzi syndrome, incarceration, and ischemia [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 43].

Intrahepatic gallbladder may mimic liver or cystic masses during diagnostic imaging, which results in extended investigation and delay in diagnosis. This delay may cause intrahepatic gallbladder perforation and liver abscess that may be considered as a hydatid cyst during imaging [8, 10, 44, 45]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in intrahepatic gallbladder is challenging because it requires hepatotomy. Intrahepatic gallbladder should be diagnosed in the preoperative period before any hepatic surgery. Failure to do so may result in gallbladder and biliary tree injury with postoperative bile leak [44, 45].

Gallbladder position anomalies pose technical challenges during standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Malposition changes the normal position of Calot’s triangle, which changes the normal relationship of the gallbladder and biliary tree. Thus, safe dissection techniques are not practical here without modifications. Patients with gallbladder malposition also have increased rates of associated biliary tree and vascular anomalies. Due to both technical challenges and associated anomalies, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with high rates of bile duct injury, ranging from 4.4 to 7.3%; in normally located gallbladders, the rate of bile duct injury is 0.7% [44, 45, 46, 47, 48].

2.5 Diagnosis and management

Most patients with gallbladder malposition are diagnosed intraoperatively during surgery for symptomatic cholelithiasis and its complications or HPB surgery. Preoperative diagnosis will help in planning and delivering safe surgical treatment. This is not possible during management of patients with biliary colic or its complications because initial imaging modalities like ultrasound (US) are enough to give treatment. However, US is not good at detecting ectopic gallbladder; its positive predictive value is only 2.7% [18]. So, surgeons should have sound knowledge of anatomical variants of the gallbladder and biliary tree. Its intraoperative identification is the mainstay of prevention of complications. The gold standard investigation modality for gallbladder malposition is MRCP [18, 47, 48], thus all patients scheduled for hepatic surgery should be evaluated for gallbladder position anomalies and associated biliary duct, vascular, and other anomalies using MRCP.

2.5.1 Left-sided gallbladder

Patients with left-sided gallbladder usually present with biliary colic or acute cholecystitis, and diagnosis is made intraoperatively. Typically, patients undergo preoperative US that detects gallbladder stones but fails to detect the position anomaly. Whenever cystic lesion are found in an atypical location and the gallbladder is not found in its normal location, the possibility of ectopic gallbladder should be considered and computed tomography (CT) or MRCP evaluation should be performed [18, 26, 40, 41, 42]. CT will show the gallbladder located to the left of the round ligament with a positive predictive value of 60% [18]. MRCP will detect the position anomaly and associated biliary duct anomalies. Associated vascular anomalies require CT angiography.

2.5.2 Gallbladder volvulus

Nowadays only 26% of gallbladder torsions are diagnosed preoperatively [7, 21]. This is because of their rare prevalence and similar clinical presentation to a common gallbladder pathology, acute cholecystitis. Similarly, there are no specific radiology features during initial imaging.

Ultrasound. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have better sensitivity and specificity, but are not cost effective in emergency situations. A high level of suspicion is important to diagnose these patients early. The typical patient with gallbladder torsion is a cachectic and kyphotic elderly woman, aged 60–80 years, presenting with right upper abdomen pain, nausea, and vomiting. On examination, vital signs are stable, and the patient is nonestrous and nontoxic with a globular mass in the right upper abdomen [7, 21, 22, 23, 33, 43]. Laboratory studies will show leukocytosis and elevated c-reactive protein (CRP). Even though they are usually missed, there are features on US, including an enlarged and distended gallbladder with increased wall thickness, absent stones and pericholecystic fluid collection, gallbladder displacement down and away from the liver and lying in a transverse position, cone-shaped hyperechoic lesion to the right side of gallbladder neck (i.e., twisted cystic duct) (Figure 3). These clinical and US findings are suggestive of gallbladder torsion. Nonenhanced CT scan has similar findings to US. GBV diagnosis can be confirmed with MDCT or MRCP. MDCT findings show an enlarged and distended gallbladder, fluids between the liver and gallbladder, and an intra-gallbladder hyperdense lesion with crease (Figure 4). MRCP shows a distended gallbladder, tapering cystic duct, and V-shaped distortion of extrahepatic ducts [22, 37, 38, 39]. Despite all these investigation modalities, the majority of patients are still diagnosed intraoperatively. Intraoperative findings are black gallbladder with inflamed surrounding peritoneum and hugely distended gallbladder in transverse position and a twisted cystic duct (Figure 5). Management involves aspiration and derotation of the gallbladder followed by cholecystectomy. Histopathological study shows hemorrhagic necrosis. The gold standard for surgical management is laparoscopic cholecystectomy [6, 14, 15, 40, 42]. However, in the absence of expertise and setup and in the presence of absolute contraindication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, open cholecystectomy is an option.

Figure 3.

US of GBV patient showing distended GB in transverse lye, twisted CD & pericholecystic fluid. (Taken from Musefa Redwan Abdella and Amsalu Midaso Titole) [

Figure 4.

CT of GBV distended GB without stones. (Taken from Bhama) [

Figure 5.

Intraoperative clockwise twisted GB. (Taken from Musefa Redwan Abdella and Amsalu Midaso Titole) [

2.5.3 Intrahepatic gallbladder

These patients usually present with symptomatic cholelethiasis and its complications. Stones and intrahepatic malposition can be diagnosed with US. CT may be needed when cystic liver mass lesions are considered in the differential diagnosis. MRCP should be considered to assess associated biliary duct and vascular anomalies.

Management is laparoscopic cholecystectomy after hepatotomy. To avoid bile duct injuries, the cystic duct must be identified at the cystic plate and followed to the gallbladder. In case of difficulties due to poor exposure and bleeding, conversion to open surgery is recommended [8, 10]. The approach to open surgery is right subcostal incision with extension to the thorax [44]. Cholecystectomy should be done in cases of incidental finding of ectopic gallbladder to avoid future clinical and imaging confusion [1, 2]. The most important thing in managing symptomatic ectopic gallbladder patients is to prevent bile duct injuries. To perform and deliver safe surgical treatment, the following measures are recommended:

Preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder malposition and associated anomalies. This will help to plan the appropriate surgical approach to complete the surgery safely.

Technical modification of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This may include port modification, such as adding port sites [40, 45] or shifting port sites (e.g., [15]). Patient position modifications can also be considered (e.g., [40]) to identify left-sided gallbladder. The patient should be put in the supine position first and then moved to the lithotomy position. Dissection technique modifications like falciform ligament lifting and fundus first approach are highly recommended [15, 40].

Conversion cholecystectomy. Surgeons should not hesitate to convert to open cholecystectomy whenever there is difficulty or doubtful anatomy.

Fundus first cholecystectomy

Routine intraoperative cholangiography, which will show detailed biliary anatomy. This is the key to performing safe surgery.

Surgeons should have detailed knowledge of the gallbladder and biliary tree and vascular anatomical variants. This is important to decrease mortality and morbidity.

Gallbladder malposition patients may present with severe calculus cholecystitis or calculus cholecystitis due to stasis like gallbladder empyema or retroperitoneal or hepatic abscess. These patients may be considered high risk for surgery. In these cases, percutaneous drainage with appropriate antibiotics and interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended [45].

Retroperitoneal and retrohepatic gallbladder patients may present with right costovertebral angle tenderness that can be confused with hepatic mass lesions or cysts as well as renal cysts or masses on preoperative US and CT scan. MRCP is the gold standard diagnostic modality in these patients.

Dissection and resection of these deep-seated gallbladders is technically difficult [1]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be considered, but the team should prepared for conversion cholecystectomy.

US and CT do not usually detect anatomical anomalies, though they can identify gallbladder stones. If the gallbladder is adjacent to the transverse colon on CT scan, MRCP should be considered to confirm diagnosis of mesocolic gallbladder. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy with technical modification is a safe procedure, but surgeons should always keep in mind the possibility of conversion to open cholecystectomy [6, 15, 16, 40, 42].

3. Conclusion

Gallbladder positions anomalies are rarely occurring conditions in clinical practice. Though further study is needed, the most commonly occurring variants in descending order of frequency are floating gallbladder, left-sided gallbladder, intrahepatic gallbladder, and retro placed gallbladder. Ectopic gallbladders are prone to increased stone formation and related complications due to the impaired function of the gallbladder. Most position anomalies are diagnosed intraoperatively during surgery for cholelithiasis or its complications because of their rare prevalence and lack of specific clinical and imaging features. Despite advancement in radiological technology, preoperative diagnosis remains difficult; the preoperative diagnosis rate is about 20%. Gallbladder position anomalies have clinical sequelae like GBV, gallbladder herniation with strangulation in floating gallbladder, and gallbladder perforation with liver abscess in intrahepatic gallbladder. Gallbladder malposition is usually associated with biliary tree and vascular anomalies that together with changed anatomy predispose patients to increased rates of bile duct injuries (7.3%).

To prevent these devastating complications, anomalies must be diagnosed preoperatively, especially in patients scheduled for hepatic resection or liver transplantation. The surgeon should have detailed knowledge of anatomical variants of the biliary system and should always consider their possible prescience during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. When position anomalies are discovered suddenly during a procedure, technical modifications to the procedure are mandatory. These may include port site or patient position modifications, falciform ligament lifting, or fundus first approach when needed. Routine intraoperative cholangiography in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and intraoperative liver US to view biliary duct and vascular structures in hepatic surgery decreases the rate of bile duct and vascular injuries.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank IntechOpen for providing an Open Access Publishing Fee support since I and my institution could not afford the funding of publishing the manuscript in Open Access.

Acronyms and abbreviations

| GBPAs | gallbladder position anomalies |

| GBV | gallbladder volvulus |

| GBH | gallbladder herniation |

| FGB | floating gallbladder |

| LtSGB | left-sided gallbladder |

| RLtSGB | right left-sided gallbladder |

| IHGB | intrahepatic gallbladder |

| HPB | hepato-pancreatico-biliary system |

References

- 1.

David E, Charles A, Stanleyr M. Gallbladder ectopia: A review of anomalies of position. 1974; 121 (2):396-400. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.121.2.396 - 2.

Teke Z, Akcam AT. Complete mesocolic malposition of the gallbladder: An unusual case report with literature’s review. Ulusal Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi. 2022; 28 :557-561 - 3.

Lee H et al. Anatomic variation of patient with a left-sided gallbladder. The Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research. 2019; 97 (6):302-308 - 4.

Gu W, Tong Z. Ectopic gallbladder: A case report and review of the literature. Asian Journal of Surgery. July 2020; 43 (9):1-3. December 2029. DOI: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.05.017 - 5.

Kim WS et al. Strangulated gallbladder by the lesser Omentum. Soonchunhyang Medical Science. Dec 2020; 26 (2):9194 - 6.

Strong RW et al. Surgical implications of left sided gallbladder. The American Journal of Surgery. July 2013; 206 (1):59-63. DOI: 101016/jamjsurg201210035 - 7.

Boer J, Boerma D, de Vries Reilingh TS. A gallbladder torsion presenting as acute cholecystitis in an elderly woman: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. Cholecystitis in an intrahepatic gallbladder, international journal of surgery. September 2017; 4 (9):3177-3179. DOI: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-588 - 8.

Chandrasekar G, Nagappa V. Cholelithiasis in an intrahepatic gallbladder. International Journal of Surgery. 2017; 4 (9):3177-3379 - 9.

Sahu SYVM, Yang SNAA. Cell sources for treating diabetes [internet]. In: Stem Cells in Clinic and Research. London, UK: InTech; 2011:156-163. DOI: 10.5772/24174 - 10.

Muguti G, Muchuweti D, Munyika AA. Congenital duplex gallbladder anomaly presenting as gangrenous perforated intrahepatic cholecystitis A case report and review of literature. East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 2013; 18 (2) - 11.

Banchini F, Capelli P. Left sided gallbladder clinical and anatomical implication. Anatomy & Embryology of Biliary Tract. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2014; 94 :203-217. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.92000 - 12.

Keplinger, Bloomston. Anatomy and embryology of the biliary tract. Surgical Clinics. 2014; 94 :203217. DOI: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.01.001surgical.theclinics.com.00396109/14/$ - 13.

Sreekanth T. Incidence of floating/wandering gall bladders: A cadaveric study and its clinical implications. International Journal of Anatomy and Research. 2017; 5 (1):3338-3341. DOI: 10.16965/L.2016.470 - 14.

Qureshi. Aberrant presentation of the gallbladder during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2009; 13 :605-607 - 15.

Nastosetal C. Methods of safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy for left-sided (sinistroposition) gallbladder: A report of two cases and a review of safe techniques. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2014; 5 :769-773 - 16.

Idu M, Jakimowicz J, Iuppa A, Cuschieri A. Hepatobiliary anatomy in patients with transposition of the gallbladder: Implications for safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. British Journal of Surgery. 1996; 83 :14421443 - 17.

Yadav A, Jain NB, Ray S, Nundy S. The ectopic gall bladder: A review. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2022; 6 (S6):32473253. DOI: 10.53730/ijhs.v6nS6.10054 - 18.

Hsu SL, Chen TY, Huang TL, Sun CK, Concejero AM, Tsang LL, et al. Left sided gallbladder: Its clinical significance and imaging presentations. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007; 13 :6404-6409. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6404 - 19.

Hochstetter F. Anomaliemder Pfortaderunddernabelvenein verbindungmitdefectoder Linkscage dergallenblase. Archivfür Mikroskopische Anatomieund Entwicklungsmechanik. 1886; 3 :369-384 - 20.

Wendel AV. VI. A case of floating gallbladder and kidney complicated by cholelethiasis, with per- foration of the gallbladder. Annals of Surgery. 1898; 27 (2):199-202 - 21.

Abdella MR, Titole AM. The clinical case report of gallbladder volvulus. Enormous Journal of Medical Sciences and Current Research. 2022; 2 (3):1040, 1-6. DOI: 10.56558/journal.ejmscr.1001040 - 22.

Pu TW et al. Acute body-neck torsion of the gallbladder. WJG. 2014; 20 (38):1-3 - 23.

Nguyen TH, Tran KH, Le XA, Nguyen HV, Ha QV. Gallbladder volvulus and hernia through the foramen of Winslow: A case report. Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2020; 93 (10):rjaa424. DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa424 - 24.

Ben Ismail I et al. Cholecystitis in a midline gallbladder: A rare ectopic location. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2022; 93 :106969I - 25.

Kohgaetal A. Strangulatedp gallbladder caused by a tip of the omentum attached to the abdominal wall: A case report. Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2017; 7 :1-3 - 26.

Gelevski R et al. True left sided gallbladder (TLSG) as incidental finding on laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Case report. JMS. 2021; 4 (1):50-53. UDC:616.366-089.81 - 27.

Tajti J, Pieler J, Ábrahám S, et al. Incarcerated gallbladder in inguinal hernia: A case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterology. 2020; 20 :425. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-020-01569-5 - 28.

LK, De Jesus RB, Torri GB, Momo M, Rodrgues LK, Ameida Ghezzi CL, et al. Gallbladder protrusion through the groin region—a very unusual femora hernia. BJR|Case Reports. 2019; 5 :20180035 - 29.

Rogers et al. Gallbladder complicating a parastomal hernia. Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2019; 4 :1-3. DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rjz107 - 30.

Kumari S. Case report and operative management of obstructed epigastric hernia containing gall bladder: a rare entity. International Journal of Surgery. 2020; 7 :3805-3807 - 31.

KM, SHX C, Ying F, AKH C. Gallbladder herniation through ventral hernia: A case report. Open Journal of Clinical and Medical Case Reports. 2019;(4):rjz2017 - 32.

Ennis G, Venade G, Silva Marques J, Batista P, Abreu Nunes A, Constantino J, et al. Intrathoracic acute cholecystitis. European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine. 2020; 7 (11):3805-3807. DOI: 10.12890/2020001764 - 33.

Bhama AR. The diagnostic dilemma of gallbladder volvulus report of a case. General Internal Medicine and Clinical Innovations. 2016, 2015; 1 (2):26-29. DOI: 10.15761/GIMCI.1000108 - 34.

Croce, Licata. Gallbladder volvulus: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2021; 15 :494. DOI: 10.1186/s13256021031157 - 35.

Reddy K et al. Laparoscopic derotation and cholecystectomy of torsion gallbladder. JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2005; 9 :238-240 - 36.

Setty N, RS et al. Cadaveric floating gallbladder and its clinical significance a case report. International Journal of Current Research and Review. 2013; 15 (1):494 - 37.

Miyata T, Sannomiya Y, Nagayama T, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder torsion by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: A case report. Clinical Case Reports. 2022; 10 :e05487. DOI: 10.1002/ccr3.5487 - 38.

Daniel, George K, Dhan T. Torsion of the gallbladder: A systematic review. HPB: The Official Journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2012; 14 :669-672. DOI: 10.1111/j.14772574.2012.00513.x - 39.

Usui M, Matsuda S, Suzuki H, Ogura Y. Preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder torsion by magnetic resonance cholangio pancreatography. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000; 35 :218-222 - 40.

Reddy PK, Subramanian RV, Yuvaraja S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for left-sided gallbladder (sinistroposition). JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2005; 9 (3):356-357 - 41.

Maetani Y, Itoh K, Kojima N, Tabuchi T, Shibata T, Asonuma K, et al. Portal vein anomaly associated with deviation of the ligamentum teres to the right and malposition of the gallbladder. Radiology. 1998; 207 :723-728 - 42.

Pereira R, Perera M, Roberts M, Avramovic J. Surgical approach to a left-sided gallbladder. BML Case Reports. 2019; 12 (8):e230681. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230681 - 43.

Paolino LA, Millan M, Bossi M, Champault G, Barrat C. Herniation of the gallbladder within a hernia of the abdominal wall associated with Mirizzi syndrome. JSCR. 2011; 4 :3 - 44.

Audi P, Noronha F, Rodrigues J. Intrahepatic gallbladder - A case report and review of literature. The internet. Journal of Surgery. 2009; 14 (1):6, 1-4 - 45.

Donati et al. Antitypical presentation of intrahepatic perforated cholecystitis: a modern indication to open cholecystectomy. Report of a case. BMC Surgery. 2014; 14 :6 - 46.

Kocabiyik. Abnormal localization of gallbladder and atresia of superior part of duodenum. SDÜ Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi. 2008; 15 (1):38-41 - 47.

Mattone E et al. Dystopic gallbladder: Rendez vousand fluorescence. Clinical Case Reports. 2018; 6 (3):522526b. DOI: 101002/ccr31130 - 48.

Tarakj A, Kocabiyik et al. Successful surgical Management of Unusual Gallbladder Anatomy through Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy of ectopic gallbladder. Cures. 2021; 13 (11):e19884. DOI: 107759/cureus1988