Abstract

The term ‘抜苦与楽 (Bakku Yoraku)’ means to remove suffering and give comfort. In Buddhism, this word means that Buddhas and Bodhisattvas save sentient beings from suffering and provide them with happiness. The qualitative difference in empathy between humans and Buddha is suggested to be related to the psychological function of self-compassion. I explore fantasy, metacognition and autobiographical memory, integral components of self-compassion during empathy, from psychological, neurological and biological perspectives. I discuss the possibility of using a picture book as an intervention for fostering fantasy. To create a new picture book, I must understand the percentages of adjectives, verbs and nouns used in the world’s most-read books. Subsequently, a new word is coined. A fantasy story is created using these words. This story should evoke warm and positive emotions, such as the Holy Bible or Buddhist scriptures. The narration of the story must be created from 1st person perspective. I hope that this article will be helpful to researchers, educators and clinicians seeking a peaceful future.

Keywords

- empathy

- self-compassion

- fantasy

- metacognition

- autobiographical memory

- picture book

1. Introduction

Dhammapada, 197

The term ‘抜苦与楽 (Bakku Yoraku)’ means to remove suffering and give comfort. In Buddhism, this word means that Buddhas and Bodhisattvas save sentient beings from suffering and provide them with happiness. This idea widely permeates our values and actions. For example, by focusing on empathising, everyone cries when they hear about the pains of close ones. Everyone also has experience to give charity. Team sports such as soccer and basketball depend on understanding teammates’ movements and intentions. Many societal situations are built on empathising with others and interactive collaboration. Empathy is a central psychological function of these actions. Empathy is defined as the ability to quickly and automatically relate to the emotional states of others, which is essential for the regulation of social interactions, coordinated activities and cooperation towards shared goals [1]. Many people are born with psychological functioning. If everyone uses these functions without discrimination, society will become peaceful and happy, and there is no need for the ideas of the Buddha and Bodhisattva. The reason for this idea, which was born about 2500 years ago, is still important today because conflicts and disputes persist regardless of their size, resulting in discrimination, prejudice, resentment and envy in people’s hearts. Secondary traumatic stress disorder (STSD) is a mental illness caused by empathy for others’ pain. Buddha’s empathy refers to the act of compassion for others without distinction. No discrimination, grudges or envy were observed. STSD, a by-product of empathising with others’ pain, also exists. It has been suggested that the qualitative difference in empathy between humans and Buddha is related to the psychological function of self-compassion. In this chapter, I explain the fantasy, metacognition and autobiographical memory included in self-compassion during empathization. Finally, I discuss the possibility of using picture books as an intervention to foster fantasy. I also refer to the crucial matters in its creation.

2. Empathy and self-compassion, and its neurological and biological bases

Empathy is a complex socioemotional phenomenon, defined as the capacity to understand and react to others’ feelings, thoughts and experiences [2]. Empathy is a crucial psychological function for understanding others’ minds. Core differentiation refers to cognitive and affective empathy. Cognitive empathy refers to the tendency to recognise, infer and understand what others think, feel or intend to do. Perspective-taking reflects the respondent’s ability to adopt the perspectives of others. Fantasy, a mental experience associated with the tendency to identify with characters in movies, novels, plays and other fictional situations, is included in cognitive empathy [3]. As opposed to cognitive empathy, affective empathy refers to caring for others’ feelings and vicariously feeling what others feel. Empathic concern refers to a respondent’s tendency to experience feelings of warmth, compassion and concern for others undergoing negative experiences, while personal distress indicates that the respondent experiences discomfort and anxiety upon witnessing others having negative experiences, and it is part of affective empathy [3]. As neural correlates of empathy, the relationships between the anterior cingulate cortex and perspective taking, fantasy and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), empathic concern and the precuneus, personal distress and the insula and somatosensory areas have been reported [4]. Biologically, endogenous opioids containing enkephalin and oxytocin are associated with empathy [5, 6].

Compassion is defined as a feeling that arises when witnessing another person’s suffering and motivates a subsequent desire for help [7]. From a Buddhist perspective, compassion is omnidirectional and includes both others and oneself [8]. Self-compassion, which can be understood as compassion for the experience of suffering, is a productive way of approaching distressing thoughts and emotions that engender mental and physical well-being [8]. Self-compassion refers to how one relates to oneself in instances of perceived failure, inadequacy or personal suffering [8]. This psychological function directs warmth and care rather than being cold and judgmental, wanting to help rather than criticise the hurt self. From a Buddhist perspective, self-compassion is similar to the unconditional love provided by one’s mother when one is a young child. In other words, this means watching over yourself as your mother watches over her child. Neural associates of self-compassion, the dlPFC and the insula have been reported [9]. Previous biological studies have demonstrated [10, 11, 12] that endogenous opioids containing enkephalin and oxytocin promote self-compassion. According to Neff [8], self-compassion is conceptualised as a bipolar continuum ranging from uncompassionate self-response to compassionate self-response in moments of distress. When considering the relationship between empathy and self-compassion, compassionate self-response raises empathy, leading to altruistic behaviour, while non-compassionate self-response may not lead to altruistic behaviour [13]. Additionally, there is the possibility of experiencing burnout [14]. Therefore, self-compassion is a central component of empathy. However, the nature of this self-compassion remains unclear. In this chapter, I hypothesised that fantasy, metacognition and autobiographical memory are connoted by self-compassion. In addition, I discuss their neurological and biological bases. Finally, I discuss the potential of picture books to foster one’s fantasy, which is included in self-compassion and is considered particularly important.

3. Role of fantasy and metacognition in self-compassion, and its neurological and biological bases

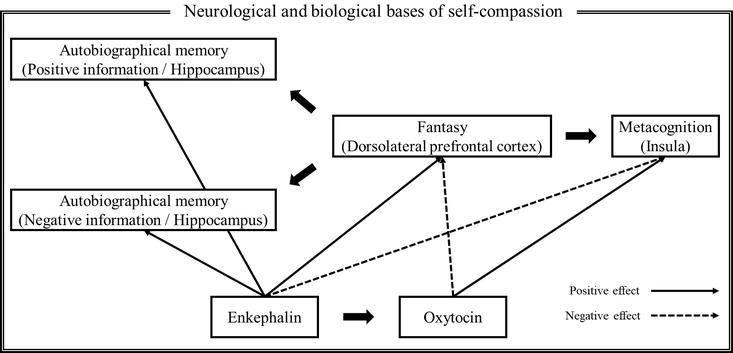

In Figure 1, the fantasy, metacognition and autobiographical memory in self-compassion, and the roles played by enkephalin and oxytocin.

Figure 1.

Neurological and biological bases of self-compassion during empathy.

The ‘fantasy’ is defined as the mental experiences associated with a tendency to identify and transpose (immerse) characters in movies, novels, plays and other fictional situations [3, 15, 16]. As the neural basis of fantasy, the dlPFC is related to this [4, 17]. In terms of biological bases, previous studies report that enkephalin enhances fantasy [18], while oxytocin reduces fantasy [19]. Metacognition is defined as the cognitive function of objectively monitoring one’s inner experiences and emotional events, which vary from moment to moment [20]. Metacognition consists of three aspects: clarity, which is related to the distinction between and understanding of one’s emotions; repair, which is related to emotional regulation and improving negative emotions; and attention, which is related to defining one’s feelings [21]. As neural correlates of metacognition, dlPFC and insula are related to this [22, 23]. As biological correlates, previous studies indicate that the endogenous opioid enkephalin reduces metacognition [24], while oxytocin enhances metacognition [25], respectively.

Previous studies that focused on the effects of fantasy on metacognitive emotional clarity process [16, 26] showed that individuals with high fantastic tendencies tend to make unbiased, and thoroughly rational decisions. Shiota and Nomura [16] also revealed that fantasy was positively associated with emotional clarity; these relationships were moderated by perspective-taking. An existing neuroimaging study [27] examined the effects of cathodal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the left dlPFC during false belief task in healthy participants.

The results showed that, compared to control group, the intervention group had a low score in the false belief task.

Previous studies also focused on the effects of fantasy on metacognitive emotional regulation [16, 28, 29, 30, 31] and reported that children’s fantastic tendency positively predicted emotional regulation; moreover, this relationship outweighed other predictor variables such as age, theory of mind and vocabulary ability. Ferguson and Olson [28] reported that playing fantasy video games reduces stress and enhances children’s motivation, which is a function of resilience in the face of failure and the desire for social interaction. Similarly, Li et al. [30] indicated that watching fantasy video material enhanced children’s scores in a Go-No-Go task and their cerebral blood flow in the left dlPFC. Shiota and Nomura [16] disclosed that fantasy was positively associated with emotional regulation; these relationships were moderated by emotional arousal.

Considering a previous study that examined the relationships between fantasy and emotional regulation from a neurological perspective [32], this study performed cathodal rTMS for left dlPFC during a cyberball task performed by healthy participants. The intervention group with cathodal rTMS felt more subjective pain, compared with the control group. This confirms that fantasy is associated with emotional regulation. This hypothesis is also supported by network of opioid receptors and oxytocin receptors in the brain. In the next section, I will provide an overview of the brain networks related to opioid receptors and oxytocin receptors. Enkephalin is an endogenous opioid that is produced by the adrenal medulla; it binds specifically to opioid receptors in the brain. Its main effects include analgesia, body temperature regulation, and feeding behaviours. Enkephalins produced by the adrenal medulla ad released into the blood cross the blood–brain barrier and are transported to the brain. The brain area that has opioid receptors to bind to enkephalin includes the lateral prefrontal cortex, the cingulate cortex, insula, thalamus, hippocampus and amygdala [33, 34]. Specifically, oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus posterior pituitary, and this process is induced by enkephalin [35]. Oxytocin is related to trust and empathy, and its receptor is in the insula [36].

Fantasy is much like a canvas in one’s mind, upon which characters, such as oneself or others, can be drawn. This mental canvas immerses people in a comprehensive image of an event [16]. Through this process, people can gain awareness, known as metacognition, by observing depictions of themselves and others on the canvas. In the act of empathising, individuals can gain awareness of themselves and others by observing the mental images that unfold. It is suggested that practicing self-compassion is a way to protect oneself, much like a mother, from the pain, sadness and difficulties depicted in these mental pictures. Previous studies supporting this hypothesis revealed that both fantasy and metacognition are associated with one’s self-compassion [37, 38]. The material in a picture created through fantasy plays a crucial role in fostering self-compassion during empathy. Although there are some differences in the external information inputs in our daily lives due to individual disparities in sensory organs, most people obtain information about brightness, colour, sound, smell and others in the same way. However, the degree of pain caused by empathy with the same content varies depending on the individual. This was thought to be caused by the difference between the physical sensations and the medium of the pictures they drew. In this chapter, I focus on autobiographical memory as a medium for this and discuss the relationship between fantasy and autobiographical memory in the next section.

4. Fantasy and autobiographical memory, and its neurological and biological bases

Autobiographical memory refers to one’s memory of their life [39]. It represents a significant intersection in human cognition, where considerations relate to self, emotions and personal meaning [39]. Fantasies have been suggested to affect autobiographical memory. When asked to retrieve individuals’ past memories, not everyone can completely recall past memories like a film (e.g., the shape of the leaves of trees in the background, expressions and gestures of passersby). People draw a subjective world using past information (knowledge), which is referred to as autobiographical memory. However, there are inter-individual differences in the canvas that depict a subjective world. In a previous study supporting my hypothesis, Patihis [40] investigated factors contributing to differences in autobiographical memory between individuals with very good autobiographical memory and controls. Patihis [40] revealed that individuals with very good autobiographical memories have a higher tendency for fantasy than controls. Merckelbach [41] examined the effect of fantasy on the quality of autobiographical memories. Participants were grouped based on their level of fantasy and false autobiographical memories (negative childhood experiences). Individuals with high fantasic tendencies recalled more qualitative content in their false autobiographical memories than individuals with low fantasic tendencies. Robertson and Gow [42] indicated that fantasy is associated with the vividness of memory in one’s own past experiences. In a neuroimaging study examining the relationship between fantasy and autobiographical memory, Young et al. [43] reported that various brain regions, including the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, left orbitofrontal cortex, left dlPFC, bilateral middle temporal pole, amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus and right precuneus are involved in the retrieval of autobiographical memory. Talbot et al. [44] demonstrated that the left dlPFC is related to the search and retrieval of autobiographical memory. In a biological study examining the relationship between fantasy and autobiographical memory, de Moura et al. [45] examined the effects of low-dose naltrexone in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. They demonstrated that a low dose of naltrexone improved memory impairment in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Tanguturi and Streicher [46] suggested that opioids alleviate Alzheimer’s disease symptoms.

This evidence suggests that fantasy and its neurological and biological bases impact autobiographical memory. Perhaps everyone may use past information (knowledge) like paint, and drawing their subjective world in what they call their own autobiographical memory. The key factor is the quality of information regarding past events. For example, when people with negative experiences (e.g., abuse) empathise with the pain suffered by another person, the information used in fantasy involves horrific content that they themselves have suffered. Because of the characteristics of fantasy, people can easily immerse themselves in pictures with horrific content, resulting in greater pain associated with empathy. Self-compassion, which involves watching oneself, is considered ineffective. In a previous study supporting my hypothesis, Nelson-Gardell and Harris [47] showed a relationship between autobiographical memory and burnout. If everyone exhibited Buddha-like empathy and supported each other, a peaceful and kind society could be established. However, our world experiences discrimination, resentment and jealousy, making life difficult. In this context, there are inter-individual differences in self-compassion, fantasy and metacognition. Therefore, interventions fostering fantasies, central to these functions, are necessary. In the next section, I focus on picture books as a noninvasive and simple intervention to foster fantasy and discuss their potential.

5. The possibility of picture book, which enhance one’s fantasy

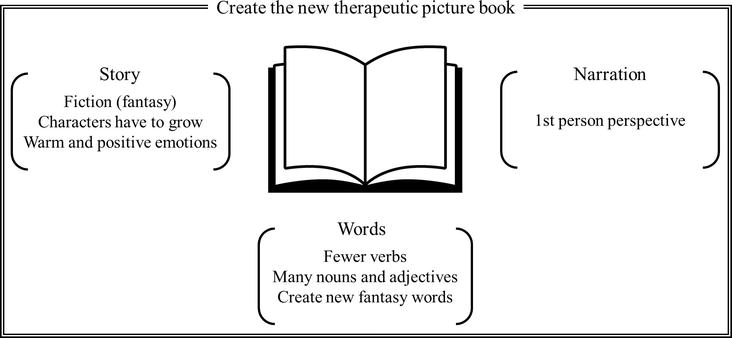

Book reading plays an important role in various aspects of human development, contributing to the evolution of human cognition [48] and shaping global values through narrative persuasion in the human mind [49]. Picture books, primarily designed for children, contain both visual and written stories [50]. They possess special linguistic and graphic features, rendering them versatile tools for early childhood development [51]. Picture books not only transport readers to a fantasy world [52] but also impart information that can be applied as real-world knowledge [50]. Paris and Paris [53] reported that wordless picture books with a clear linear plot are particularly effective in supporting early narrative skills in children, providing a sequence of pictures that form a narrative without relying on decoding skills. Additionally, Ünal et al. [54] demonstrated that picture book enhances children’s problem-solving abilities, divergent thinking, curiosity and growth mindset. These results indicate the role of picture books in developing fantasies. However, their effectiveness remained inadequate. To develop the picture book as a new, non-invasive method widely accepted for fostering one’s fantasy, I will elaborate on the role of the story, words and narration in picture book in the next sections (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The role of story, words and narration in new picture book.

5.1 The role of story in picture book

Picture books encompass a diverse array of genres, ranging from humour, folk tales, ghosts, food, dinosaurs, scientific topics, words, numbers and more. A previous study [55] investigating story preferences revealed that drama, fiction, history and love stories were favoured, with positive stories garnering more reads than negative ones [55]. Maharjan et al. [55] emphasised the significance of internal factors, such as plot, storyline and character development in a story. Wang et al. [56] revealed that there is a difference in the emotional shape of a story in a book from a low-popularity story to a high-popularity story. The emotional fluctuation was very strong in the low-popularity story, whereas all emotions were very stable throughout the books in the high-popularity story. Wang et al. [56] suggested that children do not really like emotional roller coasters, which proves the intuitive impression that children enjoy cute stories with warm and positive emotions and not strong emotional fluctuations because of their young age. Given this evidence, I suggest that the story in my new picture book is fictional (fantasy) story, where characters must undergo growth. The contents of the story should evoke warm, positive emotions, akin to the Holy Bible or Buddhist scriptures, avoiding strong emotional fluctuations. What kinds of words should I use in my new picture books? What types of linguistic characteristics contained in the story are more easily accepted? What words enhance fantasies? In the next section, I discuss the role of words in the picture book.

5.2 The role of words in picture book

In addition to story, the linguistic features were found to enhance the good reads of books [57]. What kind of words should be used to ensure that a book reads well? According to Jin and Liu [57], the complexity of words (age of acquisition of words) and sentence semantic coherence play crucial roles in making the book more approachable. Jin and Liu [57] suggested that using simple words allows readers to allocate fewer cognitive resources to word recognition, enabling them to focus more on sentence or text information processing or other cognitive processes, such as memory retrieval or information integration. Ashok et al. [58] found that successful stories used more nouns and fewer verbs. Nouns generally refer to entities that are more likely to be associated with sensory organs, whereas verbs generally refer to relationships between objects that rely less on sensory properties [59]. The use of more nouns and fewer verbs indicates that more attention is paid to describing the static aspects of objects, whereas they focus less on their actions or movements [57]. More nouns and fewer verbs may more easily induce situation construction in readers [57]. The readers then begin to immerse themselves and imagine the characters’ feelings towards themselves. According to Johnson [60], the image schema plays a critical role in structuring concepts and reasoning from the mind, as the various transformations of schema can provide order and connection to our perceptions and conceptions. Adjectives are essential for describing and differentiating concepts [61]. Jun et al. [62] investigated the relationship between the perception of adjectives and psychological activities associated with image schemas. The results indicated that the expression of adjectives was significantly associated with psychological activities in the schemas. Which words invite people into the fantasy world? Fiedler [63] suggests that words used in fiction meet specific criteria, as follows. First, the constructed words are, of course, their genesis (or origin). This characteristic makes them unique in nature. Second, words created for fiction and other purposes do not remain fictional but might become real or utilitarian words. Third, at least in part, supporters of fictional words have motives for using words. These include an interest in words and wordplay. Fourth, it is difficult to clearly distinguish between a world shaped by fictional language and the real world. Based on this evidence, words in my picture book should be simple, easily understood and appropriate for children. Using fewer verbs to describe character actions, incorporating many nouns and adjectives and creating new words that invite people into the fantasy world are also crucial. Thus far, I have explained the role of stories and words in picture books. The next important factor is the narration, which guides the story.

5.3 The role of narration in picture book

Narrative perspectives affect mental representation and text reading among readers [57, 64, 65, 66]. The narrative perspective is the basic component of story narration and determines how a story is presented to readers [67]. For example, Brunyé et al. [64] examined the effects of narrative perspective (1st person perspective vs. 2nd person perspective) while reading simple action sentences. They revealed that 1st person perspective leads to greater empathic engagement during sentence reading compared to 2nd person perspective. Child et al. [66] examined whether perspective influences the way readers engage with and process emotional information while reading. Positive texts were processed with greater ease, especially when readers experienced the texts from a 1st person perspective. Jin and Liu [57] demonstrated that a highly popular reading book uses 1st person’s perspective rather than a less popular one. Therefore, narration from 1st person’s perspective enhances readability and empathy with characters in a story, emphasising its importance in my new book.

In this section, I elucidate the key considerations in creating my new picture book. First, understanding the distribution of adjectives, verbs and nouns used in the world’s most widely read books (e.g., the Holy Bible and Buddhist scriptures) is crucial. Next, a new word is coined. This newly coined term must have a fantasy worldview in its background. It has to create some new words and examine difference in degrees of fantasy that are induced by some new words. A fantasy story is created using these words. This story should evoke warm and positive emotions, such as the Holy Bible or Buddhist scriptures. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the emotional valence and arousal of the words used in the story. The narration of the story is deliberately created from 1st person’s perspective. I explore the effects of picture books created through these processes from psychological, physiological and neurological perspectives, presenting a variety of evidence. It is necessary to examine whether new picture books using multiple languages (e.g., English, Chinese) will function similarly compared to picture book using Japanese. I would like to deliver my new picture book to educational fields around the world in next five years as a new therapeutic education method. This is a new therapeutic picture book that I want to create.

6. Conclusion

In this chapter, I elucidate the roles of fantasy, metacognition and autobiographical memory in the context of self-compassion during empathy. Prior studies have proposed relationships between fantasy, dlPFC, enkephalin, metacognition, insula and oxytocin, respectively. Additionally, it has been suggested that fantasies affect autobiographical memory. Furthermore, to create a new picture book that fosters fantasy, I explained important matters. There are constant conflicts between countries and the gap between the rich and poor is widening. I hope that this article will be helpful to researchers, educators and clinicians seeking a peaceful and kind future.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) fellows (23 K12903).

References

- 1.

De Waal FB. Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008; 59 :279-300 - 2.

Yalçın ÖN, DiPaola S. Modeling empathy: Building a link between affective and cognitive processes. Artificial Intelligence Review. 2020; 53 (4):2983-3006 - 3.

Davis MH. The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality. 1983; 51 (2):167-184 - 4.

Banissy MJ, Kanai R, Walsh V, Rees G. Inter-individual differences in empathy are reflected in human brain structure. NeuroImage. 2012; 62 (3):2034-2039 - 5.

Barraza JA, Zak PJ. Empathy toward strangers triggers oxytocin release and subsequent generosity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009; 1167 (1):182-189 - 6.

Rütgen M, Seidel EM, Silani G, Riečanský I, Hummer A, Windischberger C, et al. Placebo analgesia and its opioidergic regulation suggest that empathy for pain is grounded in self pain. National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015; 112 (41):E5638-E5646 - 7.

Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2010; 136 (3):351 - 8.

Neff KD. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology. 2023; 74 :193-218 - 9.

Engen HG, Singer T. Compassion-based emotion regulation up-regulates experienced positive affect and associated neural networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2015; 10 (9):1291-1301 - 10.

Moghaddas A, Dianatkhah M, Ghaffari S, Ghaeli P. The potential role of naltrexone in borderline personality disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2017; 12 (2):142 - 11.

Tchalova K, Beland S, Chanda ML, Levitin DJ, Bartz JA. Shifting the sociometer: Opioid receptor blockade lowers self-esteem. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2023; 18 (1):nsad017 - 12.

Wang Y, Fan L, Zhu Y, Yang J, Wang C, Gu L, et al. Neurogenetic mechanisms of self-compassionate mindfulness: The role of oxytocin-receptor genes. Mindfulness. 2019; 10 (9):1792-1802 - 13.

Kirby JN, Seppälä E, Wilks M, Cameron CD, Tellegen CL, Nguyen DT, et al. Positive and negative attitudes towards compassion predict compassionate outcomes. Current Psychology. 2021; 40 :4884-4894 - 14.

Beaumont E, Durkin M, Martin CJH, Carson J. Compassion for others, self-compassion, quality of life and mental well-being measures and their association with compassion fatigue and burnout in student midwives: A quantitative survey. Midwifery. 2016; 34 :239-244 - 15.

Davis MH. A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1980; 10 :85 - 16.

Shiota S, Nomura M. Role of fantasy in emotional clarity and emotional regulation in empathy: A preliminary study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022; 13 :912165 - 17.

Cheetham M, Hänggi J, Jancke L. Identifying with fictive characters: Structural brain correlates of the personality trait ‘fantasy’. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014; 9 (11):1836-1844 - 18.

Bershad AK, Seiden JA, de Wit H. Effects of buprenorphine on responses to social stimuli in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016; 63 :43-49 - 19.

Montag C, Schöner J, Speck LG, Just S, Stuke F, Rentzsch J, et al. Peripheral oxytocin is inversely correlated with cognitive, but not emotional empathy in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (4):e0231257 - 20.

Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you Go, there you Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. UK: Hachette; 2023 - 21.

Gohm CL, Clore GL. Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition & Emotion. 2002; 16 (4):495-518 - 22.

Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nature Neuroscience. 2004; 7 (2):189-195 - 23.

Qin P, Wang M, Northoff G. Linking bodily, environmental and mental states in the self—A three-level model based on a meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020; 115 :77-95 - 24.

Sadeghi S, Ekhtiari H, Bahrami B, Ahmadabadi MN. Metacognitive deficiency in a perceptual but not a memory task in methadone maintenance patients. Scientific Reports. 2017; 7 (1):7052 - 25.

Aydın O, Lysaker PH, Balıkçı K, Ünal-Aydın P, Esen-Danacı A. Associations of oxytocin and vasopressin plasma levels with neurocognitive, social cognitive and meta cognitive function in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2018; 270 :1010-1016 - 26.

de Jesús Cardona-Isaza A, Jiménez SV, Montoya-Castilla I. Decision-making styles in adolescent offenders and non-offenders: Effects of emotional intelligence and empathy. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica. 2022; 32 (1):51-60 - 27.

Costa A, Torriero S, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C. Prefrontal and temporo-parietal involvement in taking others' perspective: TMS evidence. Behavioural Neurology. 2008; 19 (1-2):71-74 - 28.

Ferguson CJ, Olson CK. Friends, fun, frustration and fantasy: Child motivations for video game play. Motivation and Emotion. 2013; 37 :154-164 - 29.

Gilpin AT, Brown MM, Pierucci JM. Relations between fantasy orientation and emotion regulation in preschool. Early Education and Development. 2015; 26 (7):920-932 - 30.

Li H, Subrahmanyam K, Bai X, Xie X, Liu T. Viewing fantastical events versus touching fantastical events: Short-term effects on children's inhibitory control. Child Development. 2018; 89 (1):48-57 - 31.

Kidd DC, Castano E. Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science. 2013; 342 (6156):377-380 - 32.

Fitzgibbon BM, Kirkovski M, Bailey NW, Thomson RH, Eisenberger N, Enticott PG, et al. Low-frequency brain stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex increases the negative impact of social exclusion among those high in personal distress. Social Neuroscience. 2017; 12 (3):237-241 - 33.

Peckys D, Landwehrmeyer GB. Expression of mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptor messenger RNA in the human CNS: A 33P in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience. 1999; 88 (4):1093-1135 - 34.

Zubieta JK, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, et al. Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science. 2001; 293 (5528):311-315 - 35.

Hirose M, Hosokawa T, Tanaka Y. Extradural buprenorphine suppresses breast feeding after caesarean section. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1997; 79 (1):120-121 - 36.

Wigton R, Radua J, Allen P, Averbeck B, Meyer-Lindenberg A, McGuire P, et al. Neurophysiological effects of acute oxytocin administration: Systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled imaging studies. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2015; 40 (1):E1-E22 - 37.

Hochheiser J, Lundin NB, Lysaker PH. The independent relationships of metacognition, mindfulness, and cognitive insight to self-compassion in schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2020; 208 (1):1 - 38.

Ye Y, Ma D, Yuan H, Chen L, Wang G, Shi J, et al. Moderating effects of forgiveness on relationship between empathy and health-related quality of life in hemodialysis patients: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2019; 57 (2):224-232 - 39.

Conway MA, Rubin DC. The structure of autobiographical memory. In: Theories of Memory. London: Psychology Press; 2019. pp. 103-137 - 40.

Patihis L. Individual differences and correlates of highly superior autobiographical memory. Memory. 2016; 24 (7):961-978 - 41.

Merckelbach H. Telling a good story: Fantasy proneness and the quality of fabricated memories. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004; 37 (7):1371-1382 - 42.

Robertson S, Gow K. Do fantasy proneness and personality affect the vividness and certainty of past-life experience reports? Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 1999; 27 (2):136-149 - 43.

Young KD, Bellgowan PS, Bodurka J, Drevets WC. Functional neuroimaging of sex differences in autobiographical memory recall. Human Brain Mapping. 2013; 34 (12):3320-3332 - 44.

Talbot J, Gatti D, Mitaritonna D, Marchetti M, Convertino G, Mazzoni G. Stimulating a hyper memory: A single case TMS study on an individual with highly superior autobiographical memory. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation. 2022; 15 (5):1122-1124 - 45.

de Moura FC, Xavier MKF, Rodrigues FEL, dos Santos Pinheiro MF, Machado ECL, de Moura CBC, et al. Behavioral, neurochemical and histological changes in the use of low doses of naltrexone and donepezil in the treatment in experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease by induction of β-Amyloid1-42 in rats. World Scientific Research. 2019; 6 (1):5-13 - 46.

Tanguturi P, Streicher JM. The role of opioid receptors in modulating Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023; 14 :1056402 - 47.

Nelson-Gardell D, Harris D. Childhood abuse history, secondary traumatic stress, and child welfare workers. Child Welfare. 2003; 82 :5-26 - 48.

Oatley K, Dunbar R, Budelmann F. Imagining possible worlds. Review of General Psychology. 2018; 22 (2):121-124 - 49.

Braddock K, Dillard JP. Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs. 2016; 83 (4):446-467 - 50.

Ganea PA, Pickard MB, DeLoache JS. Transfer between picture books and the real world by very young children. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2008; 9 (1):46-66 - 51.

Grolig L, Cohrdes C, Tiffin- Richards SP, Schroeder S. Narrative dialogic reading with wordless picture books: A cluster-randomized intervention study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2020; 51 :191-203 - 52.

Sundmark B. Maps in children’s books: From playworld and childhood geography to comic fantasy and picturebook art. Filoteknos. 2019; 9 :123-137 - 53.

Paris AH, Paris SG. Assessing narrative comprehension in young children. Reading Research Quarterly. 2003; 38 (1):36-76 - 54.

Ünal ZD, Menteşe Y, Sevimli-Celik S. Analyzing creativity in Children’s picture books. Children's Literature in Education. 2023:1-30. DOI: 10.1007/s10583-023-09535-x - 55.

Maharjan S, Arevalo J, Montes M, González FA, Solorio T. A multi-task approach to predict likability of books. In: Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Volume 1, Long Papers. (1). Valencia: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2017. pp. 1217-1227 - 56.

Wang X, Zhang S, Smetannikov I. Fiction popularity prediction based on emotion analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2020 1st International Conference on Control, Robotics and Intelligent System. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. pp. 169-175 - 57.

Jin J, Liu S. An analysis of the linguistic features of popular Chinese online fantasy novels. Discourse Processes. 2022; 59 (4):326-344 - 58.

Ashok VG, Feng S, Choi Y. Success with style: Using writing style to predict the success of novels. In: Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Washington: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2013. pp. 1753-1764 - 59.

Mestres-Missé A, Rodriguez- Fornells A, Münte TF. Neural differences in the mapping of verb and noun concepts onto novel words. NeuroImage. 2010; 49 (3):2826-2835 - 60.

Johnson M. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2013 - 61.

Davies C, Lingwood J, Arunachalam S. Adjective forms and functions in British English child-directed speech. Journal of Child Language. 2020; 47 (1):159-185 - 62.

Jun Z, Lahlou H, Azam Y. Image schemas in the great Gatsby: A cognitive linguistic analysis of the protagonist’s psychological movement. Cogent Arts & Humanities. 2023; 10 (2):2278265 - 63.

Fiedler S. Planned languages and languages created for fantasy and science-fiction literature or films: A study on some points of contact. Język. Komunikacja. Informacja. 2019; 14 :139-154 - 64.

Brunyé TT, Ditman T, Giles GE, Holmes A, Taylor HA. Mentally simulating narrative perspective is not universal or necessary for language comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2016; 42 (10):1592 - 65.

Brunyé TT, Ditman T, Mahoney CR, Augustyn JS, Taylor HA. When you and I share perspectives: Pronouns modulate perspective taking during narrative comprehension. Psychological Science. 2009; 20 (1):27-32 - 66.

Child S, Oakhill J, Garnham A. You’re the emotional one: The role of perspective for emotion processing in reading comprehension. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 2018; 33 (7):878-889 - 67.

Rall J, Harris PL. In Cinderella's slippers? Story comprehension from the protagonist's point of view. Developmental Psychology. 2000; 36 (2):202